চৌরঙ্গীঃ কোলকাতার দক্ষিন দ্বার

Genesis of Chowringhee

After Plassey, the necessity of keeping the English factory at Calcutta within the Fort was at end.[6] There was no felt need any more for reviving the ravaged Fort that proved its inadequacy in defending the old town and its own bulwark. The Fort was encumbered with houses close by, and had no proper esplanade for guns. Their triumph might not have been spirited enough to free the minds of English commanders from the dread of another war. That was why the East India Company favoured Clive’s decision of erecting a second Fort William expending two millions sterling.[8] The new Fort essentially differs from the old one being exclusively a military establishment and not a fortified factory of English traders as the old Fort was styled. Its construction set off in 1758 on the riverside ground of Govindpur village about a mile away from the old Fort. Before the Battle of Laldighi, the English were cooped up in the neighbourhood of the old Fort.[17] The prospect of an aerial, liveable habitation in the neighbourhood of the New Fort, attracted the European population to gradually move from the already crowded old township around the Tank Square and the old Minta, to settle in commodious Chowringhee.[6]

New Fort in Backdrop

Equipped with huge defense machinery and a formidable military architecture, the new Fort William was ready by 1773, but had no occasion ever since to exchange fires with enemies. Instead its resounding tope of canon ball routinely announced mid-day hours to regulate working life of the Calcuttans. The presence of the imposing Fort on Maidan silently reminds us of the significant role it had played in transforming the town Calcutta into a city – famously called ‘City of Palace’, the centre of British India. Following inauguration of the Fort, the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William was founded. The Governors of Bengal became the Governor Generals of India. Calcutta was reborn ushering a modern society to stay connected with rest of the world.

Beyond the European buildings lying around the Old Fort were four villages of mud and bamboo, all of which were included in the zamindary limits of the first settlement. These villages were the original three with the addition of Chowringhee. Chowringhee in 1717 was a hamlet of isolated hovels, surrounded by water-logged paddy-fields and bamboo-groves, interspersed with a few huts and small plots of grazing and arable lands. The chosen site of the Fort was on the river-bank of village Govindpore, considerably south of the old Mint. As Colonel Mark Wood’s Map of 1784 inscribes.[19] Govindpore began where the Northern boundary of Dhee Calcutta ended at Baboo Ghat, and then went up to the Govindpore Creek, or Tolly’s Nullah and that was the extreme end of the English zamindary. As Rev. Long indicated, it was ‘immediately to the South of Surman’s gardens, marked by a pyramid in Upjohn’s map.’ [17] At West, the area includes King’s Bench Walk with a row of trees separating it from the riverbank between Chandpaul Ghaut and Colvin’s Ghaut , then called Cucha-goody Ghaut At North, Esplanade Row, from Chandpaul Ghaut, hard by the New Court House on the riverside, runs into Dhurumtollah in a straight line past the Council House and the old Government House standing side by side.

Govindpore was a populous flourishing village when its entire population was removed to make room for the new Fort and its infrastructure. The inhabitants were compensated by providing lands in places like Toltollah, Kumartooly, Sobhabazar expending restitution-money. In Govindpore itself great improvements took place. The jungle that cut off the village of Chowringhee from the river, was cleared and. gave way to the wide grassy stretch of ‘Maidan of which Calcutta is so proud’.

The jungle, presumably, had been once a part of the Great Soonderband (সুন্দর বন). Many traces of trees were found at a considerable depth below the surface of the ground. These remains are thought to be those of the soondrie forest that covered the site of Calcutta when newly emerged from the waters of the Gangetic Delta. [6] Early 1789, Government resolved on filling up the excavations in the Esplanade and levelling its ground. The plan was prepared for the benefit of Calcutta in general, and of the houses fronting the Esplanade in particular. The plan extended to drain the marsh land, in expectation that the digging a few tanks will furnish sufficient earth and thus save the project cost and time. A new tank was made at the corner of Chowringhee and Esplanade, which existed till the dawn of the twentieth century. [20]

Road to Chowringhee

The road dividing the Maidan and Chowringhee was named, Road to Chowringhy [sic] by Colonel Mark Wood in his 1784 Plan of Calcutta, which in fact was a midsection of the oldest and longest thoroughfare of Calcutta, known as Pilgrim Way starting from Chitpore, Chitreswari temple at extreme North and ending at Kalighat temple in South. As late as in 1843, the proclamation included in the Special Reports of the Indian Law Commissioners has no mention of ‘Chowringhee locality’, but of a ‘Chowringhi[sic] High Road’.

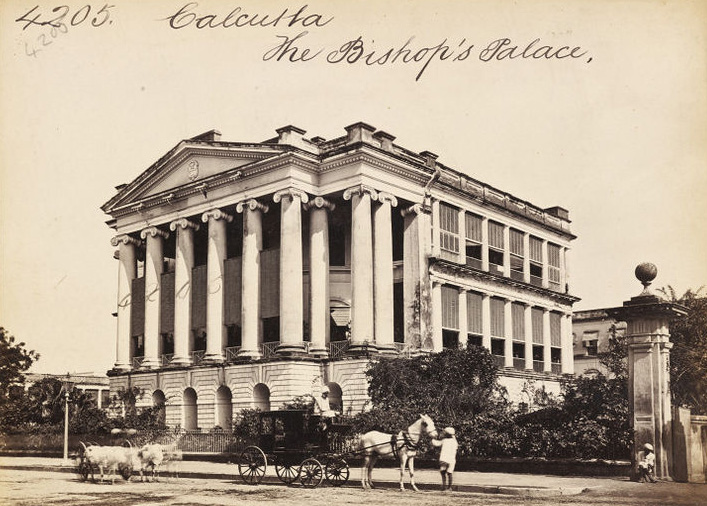

The Road to Chowringhy[sic] was initially a short stretch between Dhurumtollah and Park Street that subsequently developed into an 80 feet broad and nearly two miles long roadway commencing from the Creek where it crossed Cossitollah (later Bentinck Street) between Waterloo Street and British India Street, and ended at Theatre Road where from Rossapagla Road took the queue. Before the modern Chowringhee came into being, Cossitollah, was thronged with a large proportion of European shops and often called ‘the Indian Elysium of plebeians’. [6]. The eastern side of the Chowringhee Road is lined by handsome houses, facing the fine grassy Maidan which lies between them and the river. Houses are generally ornamented with spacious verandahs to the south, that being the quarter from which the cool evening breeze blows in the hot weather. [12] The Bishp’s Palace was the most imposing among those.

Changing Landscape

When Josua Conder visited Chowringhee, this city was ‘the quick growth of a century’, and ‘still half jungle’. He wrote, “at Chowringhee, where you now stand in a spacious verandah supported by Grecian pillars, only sixty short years ago, the defenseless villagers could scarcely bar out the prowling tiger.” His presumptions about the future of Chowringhee however were all wrong. Contrary to his beliefs, in sixty more years the city never depopulated but its strength intensified; and all these perishable palaces of timber, brick, and chunam did not disappear but multiplied more time than it should have. [7]

The above 9 lithographs of William Wood’s paintings included in his album, Views of Calcutta.published in 1833. The elegant forms of the buildings of European Calcutta heralded an important stage in the history of architecture of the subcontinent: the evolution of Western styles into forms which would become commonplace in the Indian context. This building depicted shows what became the conventional pattern, a two or three storeyed block, well-proportioned and set in a garden, and with columned verandahs protecting its rooms from the heat. Courtesy British Library

Colonel Mark Wood in 1784 marked Chowringhee on the South of Park Street away from the original locale of the village Cherangi. A decade later, Upjohn put back the district of Chowringhee as Dhee Birje, on the North of Park Street. The boundaries were shown with Circular Road on the East, Park Street on the South, Colingah on the North and a part of Chowringhee Road on the West. [17] After half a century, Dufour and Benard in 1839 put Chowringhee on both the sides of Park Street spreading over Dhurumtollah to Theatre Road. [3] Bit by bit its boundaries extended from the village at North of Park Street, then called the Burying Ground Road, to cover the whole South-East part of Calcutta. In 1802 Lord Valentia writes : “Chowringhee, an entire village, runs for a considerable length at right angles with it (the Esplanade) and altogether forms the finest view I ever beheld in any city.” In 1810, Miss Graham found Calcutta ‘like London a small town of itself ‘, but its suburbs swell it to a prodigious city. [14] Chowringhee in 1824, is no more a mere scattered suburb, but almost as closely built as, and a very little less extensive than Calcutta. [23] , “separated from Calcutta by an ancient John bazaar [Jaun Bazaar]”.[16] Chowringhee, to Rev W K Firminger, was the West End of Calcutta, socially but not geographically, a district bounded by Park Street on the North, Lower Circular Road on the East and South, and the Maidan on the West. [13]

The modern view ignores the historicity of Chowringhee. The row of buildings on Esplanade Row at the edge of Maidan becomes its Northern skirt. Its territory is nowadays more or less compatible with old Govindpore – a place no more exists.

Growing Chowringhee

A year before the construction of Govindpore Fort stared, there had been only a couple of European houses in Chowringhee. One at the corner of Dhurumtollah with entrance from that street, the other was at a little distance from it, with an entrance facing the Maidan. Most likely the first house was the General Stibbert’s House in the west end of the Dhurumtollah and in the vicinity of the Esplanade, where Mr. Farrell’ New Calcutta Academy moved in from Cossitolla Street as gazetted on 31st May 1804, much before the foundation of St Paul’s School, which was sometimes referred to as one of the two first houses in Chowringhee. The second one was indisputably the manor of Lord Vansittart at number 7 Middleton Row. It was better known as Sir Elijah Impey’s house where Impey happily stayed surrounded by an expansive deer park. In those days Maidan was ‘strangely treeless’, and Impey’s manor happened to be the foremost erection stood across it’s stretch. The site is now occupied by the Loreto Convent.

The number of houses continued to grow in isolation till 1770s. Between Jaun Bazar Road (or Corporation Street as called later), and Park Street, forty European residences, mostly with large compounds, are depicted in Upjohn’s Map. An equal number may be counted in Dhee Birjee – the quarter immediately south of Park Street. Even so late as 1824, Chowringhee was regarded as a suburb. Miss Eden calls it the Regent’s Park of Calcutta. Miss Emma Roberts spoke about suburb Chowringhee of 1831-33 – the favourite residence of the European community. From the roofs of their houses, they viewed “a strange, rich, and varied scene discloses itself: the river covered with innumerable vessels,— Fort William, and Government House, standing majestically at opposite angles of the plain,— the city of Calcutta, with its innumerable towers, spires, and pinnacles in the distance,— and nearer at hand, swamps and patches of unreclaimed jungle, showing how very lately the ground in the immediate neighbourhood of the capital of Bengal was an uncultivated waste, left to the wild beasts of the forest.” [25]

“In this part of the town,” notes Mr. Beverley in his census report for 1876, “ the streets are laid out with perfect regularity, very different from the rest of the town” – the town rising about the old Fort. [9] The report was contrary to what Miss Emma viewed over half a century ago and said, “No particular plan appears to have been followed in their erection, and the whole, excepting the range facing the great plain, Park-street, Free-School street, and one or two others, present a sort of confused labyrinth,”. and then she added ,”however, it is very far from displeasing to the eye; the number of trees, grass- plants, and flowering shrubs, occasioning a most agreeable diversity of objects.” [25] The difference between the observations of Miss Emma of Beverley evidenced the good works done in between by the Lottery Committee. “To them Calcutta is indebted for a long catalogue of improvements: and they may justly claim to be held in grateful remembrance as her second founders. Roads and paths were run across the Maidan and the familiar balustrades set up. Numerous tanks were excavated The New Market, which was built between 1871 and 1874, is another monument to the energy of the Justices which the ordinary citizen of Calcutta probably feels better able to appreciate. The grand success of the Lottery Committee encouraged the government to undertake further developmental programs under the management of the Fever Committee [9]

Chowringhee Redefined

“Chauringi [sic]) is a place of quite modern erection, originated from the rage for country houses.”, At the beginning of 19th century the people of Calcutta, as of Bombay and Madras, loved to live in garden-houses midst trees and flowers. They preferred living away from the hot, unhealthy and already crowded Town of Calcutta, to a place ‘where they could enjoy some privacy’.[17] They admired the landscape of Chowringhee. Chowringhee premises themselves were often very extensive, the principal apartments looking out upon pretty gardens, decorated with that profusion of flowers which renders every part of Calcutta so blooming. [25] The surroundings were mostly open fields among which were scattered villages, with here and there a garden house, standing in wide grounds where roamed plenty of deer, water birds, particularly the adjutant birds, or the Indian stork with a pinkish-brown neck and bill, and a military gait seen walking around. Camels and mules were not uncommon sight on Chowringhee Road. Jackals roamed at night mischievously to undermine foundations of old houses, as they did so to the Free School’s old house that fell in 1854. In spite of such small inconveniences the ‘lordly Chowringhee stood ‘equal to the finest thoroughfare anywhere; and the blessed Maidan – that enormous lung responsible for all the health and happiness of the people of Calcutta’. [20]

The name ‘Chowringhee’ denotes a new found ‘comfort zone’ in the South of Town Calcutta for the Europeans who loved a trendy hassle-free life to lead in airy environs. Whenever their comfort-zone shifted its focus the habitat moved along revising its boundaries but keeping the name unchanged. The historical maps may well justify redefining ‘Chowringhee’ in terms of habitation socially and not geographically in terms of territorial location. Chowringhee like two other old localities, John Bazaar and Taltallah, ‘came adrift from their moorings and carried away by the surging tide of population beyond Dhurumtollah toward Bhowanipore.[18] Somewhat like a Gypsy camp, the community moved on southward leaving some cohabitants behind in lesser locations.

Chowringhee Stratified

Chowringhee, we may notice, is a cluster of residential blocks of distinctive characters, categorized by racial, religious, economic differences. Blanchard in his memoir mentions: “A house in the “City of Palaces” is very apt to look like a palace. But the comparison applies only to that portion of the town where dwell the Europeans of the higher ranks, the Civil and Military officers, and principal merchants of the place. These congregate for the most part in the Chowringhee road and the streets running there from, which make up the only neighbourhood where it is conventionally possible for a gentleman to reside.” [5] This description of Blanchart found inapplicable to the whole of Chowringhee, but to some exclusive neighbourhood like. Hastings Place, at the southern end of Chowringhee. The group of streets which commemorate the various titles of Lord Hastings and his wife, who was Countess of Loudoun in her own right, are also the work of the Lottery Committee, and were designed to afford access to the Panchkotee (92 Elliot Rd ?), or five mansions, which will be found surrounding Rawdon Street, Moira Street, Hungerford Street and Loudoun Street (as it should be properly spelt). [9] We are informed by different authors that while barristers had their houses in the neighbourhood of Supreme Court, the officials, medical men, and merchants, have their residences in Garden Reach, and the numerous streets contained in the district rejoicing in the general name of Chowringee [sic]. [16] All these points out to the practice of social ranking among the European residents in Chowringhee. Chowringhee was built by Europeans for residing there in European way life, surpassing the standard of living prevailed in their homeland. Montgomery Massey penned an intimate and lively picture of Chowringhee of relatively recent time covering half a century from 1870s. [20]

Social & Religious Reservations

For a long time Indians had no place in Chowringhee, excepting very few. We find in a late 18th century map three Rustomjees on Chowringhee Lane, Jamsedjee Ruttunjee on Lindsay Street. Chowringhee allowed these rich business men of Parsee community to stay with the sahibs rightfully. It took a hundred year for the native gentlemen to share the privilege liberally with the Europeans to settle in Chowringhee. Some of those privileged ones were: Kumar Arun Chundra Singha at house 1(?) Harrington Street, Sir Rajendranath Mookherji’s house on 7 Harrington Street, Sir B. C. Mitter’s 19 Camac Street, Raja Promotho Roy Chowdhury’s 9 Hungerford Street. The presence of native houses in Chowringhee before coming of Europeans may not be improbable. Rev. Long spoke of a ‘large house’ identical to Sir Elijah Impey’s, stood on the very spot, nearly half a century before Impey. That house as referred to in the ‘Plan of Calcutta’ of 1742 ‘cannot have been an English residence’ he continued, ‘and was possibly the property of a native official’. [17]

Chowringhee in its first two centuries had been exclusively a Christian colony. The two early Bengali converts, Rev. K. M. Banerjee, and Gunendra Mohun Tagore had houses in European quarter on Bullygunge Circular Road at premises numbers 1 and 2. We are never sure if Chowringhee would have welcomed these two native Christians as residents, if so they desired. It is interesting to note, however, that there was a Hindu, of European origin, living in posh Wood Street area. Hindu Stuart was more a conservative Hindu than many native Hindus were. The European residents had tolerated Stuart’s conformity to idolatrous customs. It shows that the Europeans had no problems with native faith as such, but to them the native way of living was utterly disgraceful and unhygienic. Besides their own experience, the reactions of the overseas visitors gathered from their memoirs and letters, reinforced European antipathy toward the way of living of the Calcutta people in general, and of the lower-class in particular. One of the serious objections they had against native citizens was ‘lack of sensitivity’ and indifference toward their own surroundings. They called the native town, a black town, as it was a ‘wretched-looking place – dirty, crowded, ill-built, and abounding with beggars and bad smells’ [30]. Beyond Black Towns, even the best neighbourhoods were not completely free of such menace. “The whole appearance of Chowringhee is spoiled by the filthy huts that exist everywhere, almost touching the ‘palaces’.” These eyesores are to be seen even in the ultra-fashionable Park Street and Middleton Street, and on the Maidan in front of Chowringhee. [12] It is a repulsive scene for civilized members of any society. The problems are often thought of economy oriented and related to lower-class of the society, overlooking their cultural significance.

Living Conditions and Style

The Black Towns also includes the upper-class genteel who lived in ‘handsome houses enclosed in court-yards between the mud huts, the small dingy brick tenements, and the mean dilapidated bazaars of the middling and lower classes of natives. These Armenian merchants, Parsees, and Bengallee gentlemen of great wealth and respectability’ did never mind their environment. [25] Interestingly, the lowly tribal folks of Bengal, like the santals, keep their homes and villages clean and beautiful. The underlined social malady is an issue of critical importance for investigating the root cause of stagnation of the vernacular society. The matter is beyond the scope of present discussion. Elsewhere we discussed related issues in historical context. See: Rajendra Dutta 1818-1889

Chowringhee Today & Tomorrow

Since 1754 Chowringhee revealed itself variantly in maps, paintings, and texts. It is almost impossible to separate Chowringhee from boundary areas, or to imagine a Chowringhee excluding North of Park Street, a Chowringhee without the old Hogg Market, the Museum, Bible House, The Grand, and Firpo’s, and the like – attractions of old and recent past. For Chowringhee goers, riding an Esplanade-bound tram across the green of Maidan was a special pleasure. Alighted at Esplanade they felt already in Chowringhee, and perceived the two as inseparable. To them and some modern scholars, Chowringhee and Esplanade denote the same place and are generally called by any of the two names irrespectively. The comprehensive view of modern Calcutta embraces the grand view of Maidan and on its opposite, shiny lines of shops, hotels, restaurants, cinema halls and range of magnificent edifices built mostly by the Armenian architects who were responsible more than others for upgrading Calcutta to the City of Palace. Minney in his time wondered “if all these mighty edifices will be abandoned some day by those for whom they were built. Will the Britons say to the Indians, “We built all this for ourselves, and for you; but we can no longer live together?” [20] And so it happened. Calcutta has been losing her Oriental identity for good. The little collective will the society had earned to resist the lure of westernization is being siphoned off in the process of misconceived globalization.

NOTES

The name of the rural Cherangi (চেরাঙ্গী) changed during its transformation into urbane Chowringhee (চৌরঙ্গী). The original vernacular name [26] acquired variant renditions with some twists to suit English tongues, and spelt out fancifully by writers of last three centuries. Among the good alternatives, ‘Chowringhee’ is found most popular in the works consulted. That is the only reason why I used ‘Chowringhee’ and some other place names in certain anglicized forms as standard.

REFERENCES

1. Anonymous. 1859. The East India Sketch-Book; Comprising an Account of the Present State of Society in Calcutta, Bombay, Etc. London: Bentley.

2. Bellew. 1880. Memoirs of a Griffin; Or, a Cadet’s First Year in India, by Captain Bellew. London: Allen. Retrieved (https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QaeFDZ31SuKS9kDHiV6UQ99iWso9Gpe7upyHKD7uJymaDFKZOeWiERI3n2I2aX4TozdjSzDJP8KSMGKwxIp2QyYMijIkC9LDrZ5rrD8ee7utuIuTAt4mkqAM9uu-jq3vjAx2M3xYMFMxXW8OHNamEuOXWPDkU0yA-yq9EUwZPN8_ifFCoA2tHKD61OGFj9SPebPjy).

3. Benard, Dufour and. 1839. “Calcutta 1839: A French Map 1839_DufordandBernard.” Retrieved (http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00maplinks/colonial/calcuttamaps/rouard1839/rouard1839.html).

4. Bengal Almanac. 1851. BENGAL ALMANAC , With A Companion a N D Appendix. 1851st ed. Calcutta: Samuel Smith. Retrieved (https://books.google.co.in/books/about/The_Bengal_Almanac_for_1851.html?id=4UNBAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y).

5. Blanchard, Sidney Laman. 1867. Yesterday and Today in India. London: Allen. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/yesterdaytodayin00blan#page/n3/mode/2up).

6. Blechynden, Kathleen. 1905. Calcutta Past and Present. London: Thacker. Retrieved (https://archive.org/details/calcuttapastand02blecgoog).

7. Candor, Josua. 1828. Modern Traveller: Popular Description, Geographical, Historical, and Topographical ; Vol.3 India. London: Duncan. Retrieved (https://archive.org/details/moderntraveller05condgoog).

8. Carey, William. n.d. Good Old Days of Honorable John Company; vol.1.

9. Cotton, Evan. 1907. Calcutta Old and New: A Historical and Descriptive Handbook of the City. Calcutta: Newman. Retrieved (https://archive.org/details/calcuttaoldandn00cottgoog).

10. Curzon,George Nathaniel, Marquis of Kedlesta. 1925. “British Government in India; vol.1.” Retrieved (https://books.google.co.in/books?id=t_qdnQAACAAJ&dq=british+government+of+India+curzon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjtgteC2MnXAhVEqI8KHe-DBeoQ6wEILTAB).

11. Deb, Binaya Krishna. 1905. The Early History and Growth of Calcutta. Calcutta: RC Ghose. Retrieved (https://archive.org/details/earlyhistoryand00debgoog).

12. Dewar, Douglas. 1922. Bygone Days in India; with 18 Illustrations. London: John Lane. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/bygonedaysinindi00dewauoft#page/n15/mode/2up).

13. Firminger, W. K. 1906. Thacker’s Guide to Calcutta. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/thackersguidetoc00firm#page/n7/mode/2up/search/’socially+but+not+geographically).

14. Graham, Maria. 1813. Journal of a Resdence in India. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Costable. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/journalaresiden00callgoog#p age/n6/mode/2up).

15. Hamilton, Alexander. 1727. A New Account of the East Indies; Being the Observations and Remarks of Capt. Alexander Hamilton from 1688-1723. Vol.1. Edinburgh: John Mosman [print]. Retrieved (https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QacjxhiAm8rzif8UIk9TDXspCahRSpGTJAm4B4cNBUSur1ofIcI-zAg5Za6SGU0KEoBJJ0rawcvPDm3vIiVfY_AZMXqlsbCB7DFd_Q2mmMeTe-lppWWArhBGhJyND193wpzwke4Pr80-cyeInTGT6QK0EtQ5684QSuXLM8N5EGEHC5kHd6fucZw-MT5827LyRLvNA).

16. James, Edward. 1830. Brief Memoirs of John Thomas James, D.D: Lord Bishop of Calcutta. London: Hatchhard. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/briefmemoirsofla00jamerich#page/n5/mode/2up/search/ancient).

17. Johnson, George W. 1843. The Stranger in India; Or, Three Years in Calcutta. Vol. 1(2). London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/strangerinindia00johngoog#page/n46/mode/2up).

18. Long, Rev.James. 1852. Calcutta in the Olden Time – Its Localities. Art.2 – Map of Calcutta. Retrieved (https://books.google.co.in/books?id=cQc2AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA275&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false).

19. Mark Wood. 1792. “Plan of Calcutta: 1874-1875.” Retrieved (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/82/Kolkata_Old_Map.jpg).

20. Massey, Montague. 1918. Recollections of Calcutta for Over Halh a Century. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink. Retrieved (https://www.google.co.in/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjRr_WylsPXAhUDV7wKHTWJAXcQFggxMAI&url=https%3A%2F%2Farchive.org%2Fdetails%2Frecollectionsofc00massiala&usg=AOvVaw3uvydXqyjqB3xbkOOZe4jp).

21. Minney, R. J. 1922. Round about Calcutta. London: Oxford U P. Retrieved (https://archive.org/stream/roundaboutcalcut00minnrich#page/n5/mode/2up).

22. Monkland. 1828. Life in India, or the English at Calcutta; vol.2.

23. Montefiore, Arthur. 1894. Reginald Heber: Bishop of Calcutta, Scholar and Evangelist. New York: Revell. Retrieved (https://archive.org/details/reginaldheberbis00bric).

24. Ray, A. K. 1902. Calcutta: Town and Suburbs; Pt.1 A Short History of Calcutta. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat. Retrieved (https://books.google.co.in/books?id=-Lo5AQAAMAAJ&q=calcutta+town+and+suburbs+ak+Ray&dq=calcutta+town+and+suburbs+ak+Ray&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjDnrz11MnXAhUCN48KHdgEDQUQ6AEIJzAA).

25. Roberts, Emma. 1843. “Memoirs of Emma Roberts. In Memoirs of Literary Ladies of England; Ed. by Mrs Elwood; vol.2.” in Oxford University, vol. 2. London: Colburn. Retrieved (https://books.google.co.in/books?id=ROsQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA333&lpg=PA333&dq=memoirs+of+emma+robert&source=bl&ots=c_ubDSyGKS&sig=PW6CgPPZ3uZuZq0Ev71kl_Ll7vU&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiI5PPQ0cjXAhXHto8KHTQ7DFQ4ChDoAQgmMAA#v=onepage&q=memoirs of emma robert&f=false).

26. Thacker, Spink. 1776. “Alphabetical List of the Streets in Calcutta, Howrah, and the Suburbs.” Calcutta: Thacker, Spink.

27. Wilson, Charles R. 1895. The Early Annals of the English in Bengal; Summarised, Extracted, and Edited with Introductions and Illustrative Addenda; Vol.1. London, Calcutta: Thacker. Retrieved (https://archive.org/details/earlyannalsofeng01wilsuoft).

Really good web site – most informative. I am researching old theatres and their location. Do you have any idea exactly where ‘Mrs Bristow’s private theatre’ was situated in Chowringhee Road (operated 1789-90). Is it on the site of the the later Chowringhee theatre? Many thanks for any thoughts on this.

LikeLike

Thank you Peter for nice comment. I would be too happy if you find the following useful:

It is a wonderful project and wish you complete it soon. Warm regards

LikeLike

You may find this reference to Mrs Emma Bristow’s Private Theatre of some use:

India’s Shakespeare: Translation, Interpretation, and Performance

edited by Poonam Trivedi And Dennis Bartholomeusz, Poonam Trived

https://books.google.co.in/books?id=tvV_A-ayyZUC&pg=PA233&lpg=PA233&dq=mrs+bristow+chowringhee&source=bl&ots=VVFm_I9GiI&sig=iB7DPk956Qd6u1RhA3SxeIfKQWQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwic5v_Ppt7ZAhUJQI8KHdLhAlUQ6AEIPjAB#v=onepage&q=mrs%20bristow%20chowringhee&f=false

LikeLike

Many thanks for this most helpful information. Best regards.

LikeLike

You might have noted, the old building of the Chowringhee Theatre had a look of private residential bungalow

I find some anomalies in my post on Calcutta Theatre, especially in context of our new findings. You may like to have a look and suggest possible interpretation

Thanks

LikeLike

Dear Sir

Thank you for sharing. Hope to meet you in January 2018.

Warm regards

Ashish Sanyal

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike