BACKDROP

Antoine De L’Etang (1757-1840) is the other chivalrous adventurist, who was like Julius Soubise (1745-1798) [Puronokolkata], deported to India in the late eighteenth century for outrageous romancing. His last-name appears in many styles in literature, such as ‘de l’Etang’, ‘De L’Etang’ and ‘Deletang’ that he used in his books. About his early life we know nothing much for sure excepting that he was born on the 20th July of 1757 in Versailles to a former cavalry captain Antoine and Jeane Barbier [France], a year after the first Treaty of Versailles was signed. The Treaty, which was a diplomatic agreement between France and Austria, needed a redo by arranging a holy marriage between the two royal houses. The 15-year-old Princess Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna, by proxy, got married on 19 April 1770 to Louis-Auguste, the eldest grandson and the heir of the French monarch Louis XV. Next month, Marie met her husband for the first time in the official wedding ceremony held at the Palace of Versailles on 16 May 1770. Her conjugal life though was never so happy as they admittedly had no common interests to bring them together. The couple would not consummate their marriage until seven years later, which became a popular matter of discussion and ridicule both at court and among the public. [Covington ]

Marie charmed many of her contemporaries in her court life of extravagance. Around 1778, a rumour spread out that Marie was having an affair with her close companion Hans Axel von Fersen (1755-1810), a Swedish count, and questions arose regarding the paternity of Marie’s children. To avoid causing a scandal von Fersen left for the war in America in the early part of 1780. [Jehaes]

DE L’ETANG IN VERSAILLES

In the Palace of Versailles, where his father was said to be in service, Antoine De L’Etang, had his first employment in 1770 as a Page of Honour to Marie, the would-be-queen, on her arrival to the Palace. De L’Etang, then a boy of 13, and Marie, 2 years older, fell in love with each other. This story of young love, though not improbable needs to be verified before we accept it seriously like the case of von Fersen whose affairs were recorded in historical context. [Chateau] After four years, De L’Etang got promoted in 1774 to a Bodyguard of the King’s Guard du Corps in the company of Jean de Noailles (1739-1824), and Superintendent of the Royal Stud Farm. ‘He was a magnificent horseman, tall and handsome, with a courtier’s polished manners. [Dalrymple]

We have no evidence, however, either against or for, in support of the repeatedly told episode that it was because L’Etang was openly devoted to his Royal mistress, and his conduct was such that gossip reached the ears of King Louis XVI, and prompted him to issue a sudden order to have the young Chevalier sent out to India in 1784 for good. [Cotton ]

DE L’ETANG IN PONDICHERRY

Antoine de l’Etang was sent to the Governor of Madras in 1784 with a sealed letter recommending for his placement in Indian territory and prohibiting him to go out of India ever. L’Etang joined the French infantry to serve against the British East India Company. According to Cotton, it was L’Etang who on his own had left Versailles to escape a lettre de cachet [Britannica] going to be signed by the King and countersigned by a secretary of state to authorize his imprisonment [Cotton]. In such a case, it would have been a very high-risk for l’Etang to keep his identity undisclosed once enrolled in the out-stationed French regiment in Pondicherry. His first assignment was in the post of a Sergeant of sepahis and an adjutant to his senior officer, and that was a catastrophic fall from the alleged post of Superintendent of the Royal Stud at Versailles. The acceptance of such a humble position for the Chevalier might support the view that it was him who had escaped to India incognito without any official letter in hand. It was the time when his troops one day “suddenly came upon a Colonel Maxwell (b.17–; d.1803) of the English East India Company reconnoitring with a single sepoy (sepahi) in attendance. The Chevalier could easily have captured him, but fearing what the fanatical and so-called ‘democratic’ mob in Pondicherry might do to an English prisoner, he chivalrously distracted the attention of his men and allowed Colonel Maxwell to escape..” [Dalrymple] Spooner who neatly compiled conflicting biographical data of the Chevalier from family sources followed blindly Sir Weldon Dalrymple having had ‘no reason not to believe Sir Weldon’s story, he was highly respected in his field’ [Spooner]. Most likely, Colonel Maxwell (17– -1803) had been in Pondicherry before shifting his HQ to Cauverpatam in 1790 to join the third Mysore War commanding the Centre Army against Tipoo Sultan.[Vibart]

The head of the family, M. Vinditien Guillain Marie Blin de Grincourt was born in Arras, France around 1740s, and probably the first generation to make a home in Pondicherry outside the homeland. Blin de Grincourt married a local beauty Marie Madeleine Cornet on 28 July 1766. Marie Madeleine, born 15 March 1747 in Pondicherry, arguably had an oriental streak being a great-granddaughter of a Hindu convert, Marie Monique, from Bengal who had married Brunet Claude- a French on 7 February 1703. It was relatively a recent idea that ‘if proselytization of Christianity in India were to be successful, it had to target caste, class and gender.’ [Dutta] Therefore for a Bengali high cast Hindu lady to be converted before 1703, long before the establishment of Serampore Mission, is unimaginable. In the late 17th century the place Nagori (Dacca-Bhawal region) where a massive conversion took place under Dom Antonio, the zamindar of Bhushana, might be, however, the home of the Maria Monique as it appears outwardly.

Therese Josephe Blin de Grincourt was born in 1768 to Marie Madeleine and Blin de Grincourt. Chevalier de l’Etang begged Monsieur Blin de Grincourt for his daughter’s hand. Theresa was married to him on 1 March 1788 in Pondicherry. She and the Chevalier raised a family of two sons: Ambroise and Eugene, both died unmarried, and three daughters: Julia Adeline Antoinette, Adeline Marie, and Virginie. While Pondicherry was the hometown of the family, they might sometimes stay in other places like Bombay and Madras as well.

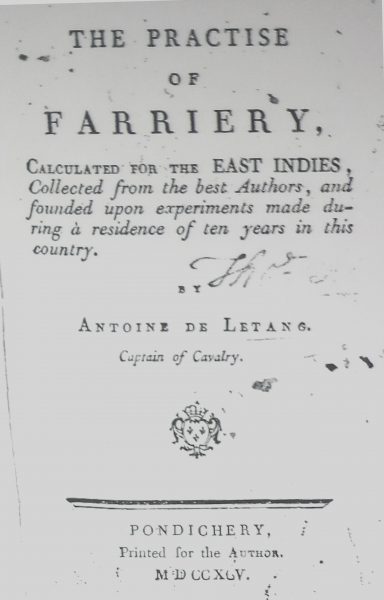

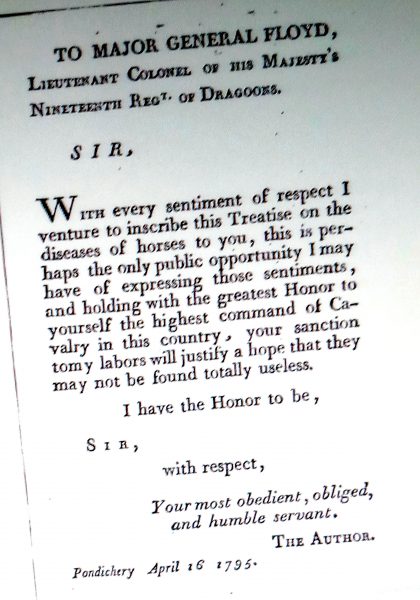

Pondicherry was under siege in August-October 1793. The victorious British had captured all the French guards. Colonel Maxwell spotted I’Etang among them. In remembrance of his generous help, the Colonel sent him with a letter of recommendation to the Governor of Madras. “Released on his parole in Madras, De L’Etang with many other French officers was hospitably received among the English residents there. It was an opportune time for him to publish his first book in India entitled “The Practice of Farriery: Calculated for the East Indies, collected from the best authors, and founded upon experiments made during a residence of ten years in this country.” De L’Etang himself printed the book and dedicated it to Major General Floyd, Lieutenant Colonel of the Majesty’s Nineteenth Regiment of Dragoons, dated Pondicherry, 16 April 1795. We learnt that before leaving the place finally, De L’Etang ‘was able to dispose of the whole edition among his English friends’ [Blechynden]. L’Etang, now freed, set to leave for Calcutta with his wife and children: Julia, Ambroise, and the new-born Maria, leaving behind Pondicherry and his long association with the Royal Service of France.

DE L’ETANG IN CALCUTTA

Antoine De L’Etang must have been already disturbed seeing France at its historic turning point amid rebellious upsurge: abolition of the monarchy, the assassination of Louise XVI and thenceforth of Queen Antoinette. The Siege of Pondicherry made him desperate to find for himself a new way of life outside the French sphere of influence. Private entrepreneurship or employment under the British East India Company were the two possible choices remained for him. Calcutta provided both the opportunities in course of time.

De L’Etang met Chevalier Julius Soubise. Soubise was, since a decade in Calcutta, struggling to overcome a series of setbacks in his ventures for which his follies and some bad lucks were mostly responsible. Soubise and his family have now moved in Dhurrumtollah from Cossitollah neighbourhood living close to his new establishment, the Calcutta Repository, built in early 1795.

THE CALCUTTA REPOSITORY

On 19 February 1795, the Calcutta Gazette published an elaborate announcement of launching the Calcutta Repository with its complete business profile, including its services, facilities, and t&c. Very likely, the news report was penned and sponsored by Soubise himself.

“As every convenience that could be devised has been adopted to render them complete, he flatters himself they are, without exception, the best stables of any in India; and as Mr Soubise’s professional knowledge and long residence in the country enable him to pay every attention to that noble animal, the horse, he hopes to obtain a share of that liberal patronage which has so often distinguished this Settlement. The Repository, which is now open for the reception of horses, is situated to the north of, and nearly behind Sherburne’s Bazaar [where Chandni Market now located], leading from the Cossitollah down Emambarry Lane, and from the Dhurumtollah by the lane to the west of Sherburne’s Bazaar.

With a view to the further convenience of the Settlement, Mr Soubise has erected one [range?] of stables, nine feet wide, for the accommodation of breeding mares, or horse who have colts at their side. There are likewise carriage houses, with gates, locks and keys to each, which render them very complete. The terms of the Repository are made as reasonable as possible and are twenty-three Sicca Rupees per month, in which is included every expense (medicines excepted) for standing, syce, grass-cutter, feeding, and shoeing, and for standing at Livery only at five Rupees per stall. Further particulars may be known on application to Mr Soubise at his dwelling house, near the Repository, or at the menage.”

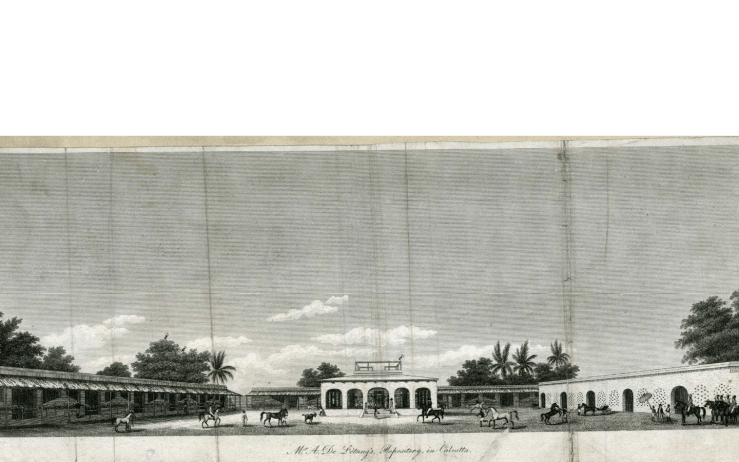

It may be noted here that the location of the Calcutta Repository as described meticulously in the above advertisement completely opposed the locational details given by Miss Blechynden who maintained that “This building stood at the Chowringhee end of Park Street, on the site which was later occupied by the Asiatic Society’s house” [Blechynden] Roberdeau on the other hand, found the correct location, nos. 182 and 183 Dhurrumtollah Street later occupied by Cook’s livery stables, but mistakenly thought that ‘It was originally an enterprise of Chevalier Antoine de L’Etang (1757-1840) who came to Calcutta in 1796’ disregarding the fact the building was inaugurated in February 1795 much before l’Etang’s appearance on the scene.

When in 1795 Soubise introduced De L’Etang to Blechynden, he was not too pleased to notice his inclination to grab opportunities flouting moral justifications. “Soubise’s new partner did not hesitate to have him imprisoned for his debts, Blechyndon was disgusted by the inhumanity of ‘Detang (as he called him).” When De L’Etang resisted sending Soubise his half of the stable’s profits in prison, Blechyndon exclaimed ‘How is the poor Devil to live! a jail is misery enough without adding Starvation to it!’ [Blechynden, R] De L’Etang’s conduct had distressed Blechynden as reflected in his diary notes: “I am sick of this trouble and more so at the roughness of his treatment of that unfortunate man. That Soubise is an extravagant fellow is very certain but Deletang should remember that he had persuaded him already – and need not overwhelm him with rough usage whilst in duranee.”

In contrast to the gruesome way De L’Etang treated Soubise, he was found too kind and gracious in his instantaneous dealings with Colonel Maxwell – irrespective of the fact that Maxwell belonged to his enemy camp, and Soubise his business partner. It may suggest that l’Etang with his French aristocracy had some innate prejudice against the blacks.

Soubise had never a chance to overcome the racist resistance he faced firstly from being within the British society, and then when he was exiled to colonial India governed by racial discrimination. In an environment of mistrust, Soubise had little opportunity to secure business credit on fair terms. His appeals for seed money turned down without showing any good reasons. Soubise requested Blechynden to be one of his securities to the Asiatic Society for Rs 5000. Blechynden lied and declined politely.[Cohen] Such a situation sometimes made Soubise desperate to take deceptive means and end up in jail. As for the proposed project, De L’Etang could have succeeded in obtaining a permit on depositing the security money to run a menagé on his own on the vacant site of the Asiatic Society. There was, however, no supportive advertisements or news reports surfaced so far but we find a mention of ‘the Riding School kept by De L’Etang’ in Henry Roberdeau’s Accounts of life in Calcutta in 1805 – the year in which the Society’s building completed, leaving no room thereafter for the menagé to exist and for Roberdeau to witness it. Most of the other pieces of information Roberdeau provided about Antoine De L’Etang were seemingly borrowed from unverified sources.

The Calcutta Repository suffered an irrecoverable loss on Awadh horses within a couple of years. In the same month, Soubise was imprisoned ‘for shortchanging a customer on the sale of a horse in another complicated credit transaction. Pawson, the owner, had to sale the stables by lottery. The lotto winner at first made an offer to Blechynden. As he was not ready with the money, the offer went ultimately to De L’Etang. The transaction completed by December 1797.

AUCTION HOUSE

The failure could not deter Soubise to take another stake in another sphere of business. The cherished dream of the penniless was now – setting an Auction House at the ‘old Harmonic’ – the grand tavern equipped with capacious accommodation once used for holding large parties, and ball. The plan made Blechynden much worried: ‘how then could Soubise prosper without money — without interest—without friends — and without a particle of public confidence’? He sounded genuinely disturbed and more so seeing that his friend Pawson was already under the spell of Soubise’s reverie. Determination of Soubise made way for developing the Auction House in the Harmonica of old fame. While the names of Pawson, Blechynden, and de l’Etang were frequently mentioned but it is not clear, however, who funded the project.

What we know for certain is that those days, Soubise was greatly inspired by his recent rapport with Nilmoni Halder, a resourceful Bengali businessman of Bowbazar. Halder came forward from outside Soubise’s circle, to support his new enterprise, the Riding School, with money and encouragement. The Calcutta Gazette advertised Riding House on 5 July 1798, inviting public attention to its sessions. The Riding House proved in less than two months to be the most ominous event in the life of Julius Soubise and his family. On 14 August Blechynden accompanied by De L’Etang found him in the gallery with fatal injury by accidental fall from a devilish Arab stallion. Next day, 25 August 1798 the Calcutta Gazette reported the death of Julius Soubise and the Asiatic Annual Register made the news recorded in its vol.1: 1798-99.

The Calcutta Gazette on 30 August 1798 advertised the ‘Sale of Horses by Public Auction’ to be held every Wednesday at 10 o’clock in the forenoon. It was the beautiful Arabian saddle ‘Noisy’ – a property of Joseph Thomas Brown – to be on auction sale. The report specified that: the sale was for the benefit of Mrs Soubise, and the auctioneer was the nobleman, Mr A. L’Etang. As we know, Blechynden despite his best efforts could not help Soubise’s family to get out of their financial crisis. Pawson died in 1802. We hardly know what happened to Catherine Soubise thereafter. De L’Etang became now the owner of the Calcutta Repository, The Auction House and the Riding House, and continued to run all the establishments ably by himself.

II

ENTERPRISES & EMPLOYMENTS

From the beginning of the 19th century, De L’Etang ran a riding school, combined with a veterinary business, and auction rooms for the sale and purchase of pet animals and fancy goods. Calcutta Gazette reported every week the events of De L’Etang’s establishments carrying the legacy of Julius Soubise. Unlike Julius Soubise, De L’Etang preferred to live away from the tumult of the city life in places like Regent Garden, and Falta, but his hub of activities had been the neighbourhood of Lallbazaar-Cossitollah-Dhurrumtollah until he shifted to Ghaziabad in around 1816 for the rest of his life.

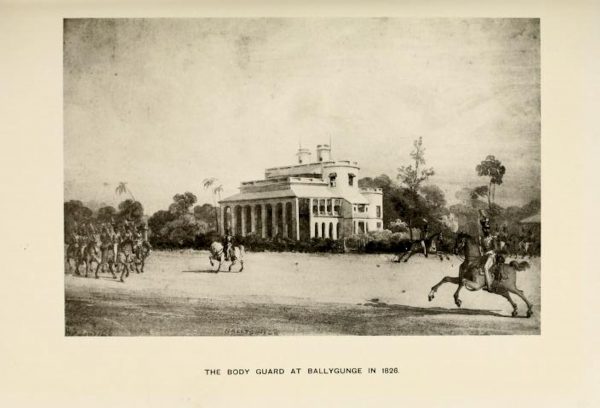

We understand from the contemporary newspaper sources that in 1802 De L’Etang was appointed as a veterinary surgeon to the Bodyguard of the Governor-General of Bengal – a cavalry regiment of the British Indian Army. [Calcutta Gazzette] The post, created for the first time in Military Consultations of the 25 February 1802, was abolished within 4 years on account of some inter-personal issues.[Hodson] De L’Etang was out of the job for a while since the beginning of the year 1806.

In 1807 an epidemical Catarrh [a flu-type disease] had attacked the horses of the Body Guard. To expel the epidemic in the Corps, the Commanding Officer Herbart Call fixed upon Mr ‘Deletang’ (sic) whom he thought “the most proper person to apply to on the occasion from his having formerly been attached to the Corps and better acquainted with the construction of the horses than any other person of his description in Calcutta.” [Hodson]

Toward the end of the year, as we find in a news report dated Sunday, 5 November 1807, that De L’Etang had met a road accident near Bridge Tollah [probably the original name of Birjee village] and Chowringhee crossing. A drove of bullocks pushed his phaeton carrying him and his brother-in-law, Mr Blin, up to a flooded ditch where they all were instantly submerged. De L’Etang received the most prompt and effectual assistance, and being carried to Mr Uvedale’s, he was restored to life, and completely recovered in the course of a few hours. [Asiatic]

OUDH

After about four years De L’Etang, for reasons unknown, leaving his veterinary job went to Lucknow. “Monsieur De L’Etang was allowed to enter the service of the Nawab of Oudh as the Superintendent of the Nawab’s Stud, and a Veterinary Surgeon.” [India Office 1811] Apparently, De L’Etang did not get on well with the native officials of the Court. Before long he was found at fault as a veterinary surgeon, being responsible for the sudden death of several horses. Complaints made by the new Nawab Wazir of Oudh, Ghazi ud-din Haidar, to Lord Moira, the Governor-General, against the Resident of Lucknow, Lieut Colonel John Baillie. Accordingly, De L’Etang was ordered along with three other Europeans, namely, Dr John Law, James Henry Clarke, and Captain Duncan Macleod. [India Office. 1814]. After the dismissal, De L’Etang was unable to claim his unpaid salary. [Rootweb] This unfavourable incident, however, mattered little to De L’Etang in advancing his career. Following the dismissal, De L’Etang managed stud farms for the EIC. [Baillie] The Marquess of Hastings in his Diary, under date, Lucknow, Nov. 1814, was pleased to write of him with candid appreciation: —

“Mr De l’Etaing been here six weeks is a man of exemplary character and most polished manners; and is moreover highly qualified for superintending a stud (the function he was to discharge here), having held such an office under Louis XVI. in France. Luckily I can reinstate the poor man in the appointment he held in our stud.”

REENSTATED IN CALCUTTA

After a lapse of over 12 months from the His Excellency’s diary date, “Mr De L’Etang was given the appointment on the 19th January 1816 as a Sub-Assistant to the Superintendent of the Hon’ble Company’s Stud, with a salary of Sonat Rupees 400 each per mensem.”. He was promoted to the post of the Second Assistant on July 29th, 1824, and the First Assistant in November next year. It is known from the Bengal Directory and Annual Register of 1838 that Chevalier Antoine De L’Etang was continuing in the same position of the First Assistant under Superintendent Major Mackenzie in the Stud Department, Buxer, Central Provinces. He held this position till he died on 1 December 1840 at the age of 84.

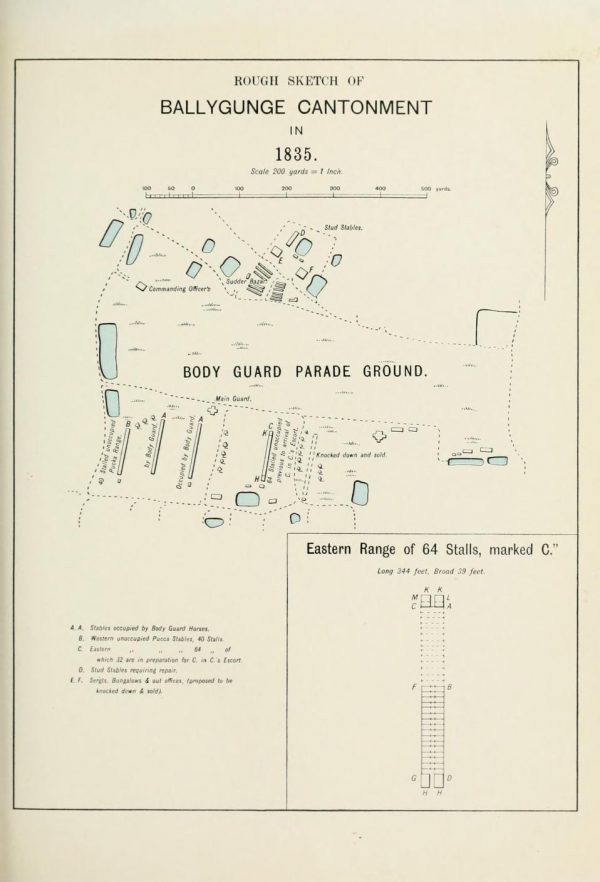

During the year 1 801, land at Ballygunge was first appropriated by Government as a Cantonment for the Body Guard. The Governor-General directed Lieutenant Daniell to clear the ground at Ballygunge to be occupied as a Cantonment for the Body Guard and to erect temporary Buildings thereon for the accommodation of the Serjeants, Men and Stores of the Corps, together with a Guard Room, Hospital and Stabling. De L’Etang’s first appointment in Calcutta was in 1803 as a Veterinary Surgeon to the Bodyguard of the Governor-General of Bengal – ranked lowest in the department. [Hodson] After the Oudh episode, the Governor-General graciously restored De L’Etang in EIC’s service in January 1816, as a Sub-Assistant to the Superintendent of the Hon’ble Company’s Stud, with a salary of Sonat Rupees 400 each per mensem. On 29 July 1824, Du L’Etang was promoted to the Second Assistant, and in November next year, he became the First Assistant in the Stud Department. Bengal Directory. The Annual Register of 1838 shows De L’Etang was still continuing in the post of the First Assistant under the Superintendent Major J. Mackenzie, Stud Department, Buxar. Over his long tenure of service, he could reach up to the rank of the First Assistant to the Superintendent without having ever a decision-making authority.

PUBLICATIONS

After long thirty-six years, De L’Etang took time to publish two more books on the health management of horses updating his previous book. It so appears that De L’Etang was in touch with Blechynden and it was he who translated the two manuscripts for De L’Etang to publish in 1831. We know from Blechynden’s diary that it was an embarrassment for him when De L’Etang told that the money he had received earlier was not his fees for the translation work, as expected, but a loan. The book, Genealogical Stud Book containing the Pedigrees of all Stallions from the year 1795 to 1 January 1832, in the Government and private Studs (printed in India Gazette Press, 1831) was dedicated to Lord Bentinck; the other one, ‘Stud Book’ followed next year. There was no much impact of the two professional publications on his service career. In fact, his service life in India was never found good enough if we consider what he had achieved earlier in France. It may suggest that the reasons are rooted in nationalist bias – separatism of a different order.

ATTAINMENTS

Lord Hasting’s above-quoted Diary entry reveals certain inconsistencies between what he thought of De L’Etang and how he acted upon in reinstating ‘the poor man’. His Lordship was demonstratively sympathetic toward De L’Etang’s loss of a job at Oudh Stud, and was much impressed finding him ‘highly qualified for superintending a stud’ since he ‘held such an office under Louis XVI in France.’ Nonetheless, He made De L’Etang, no better than a humble Sub-Assistant to the Superintendent of Stud, EIC.

Lord Hastings apart, there were two premier historians, Evans Cotton, and Kathleen Blechynden, and chroniclers like Henry Roberdeau, Weldon Dalrymple-Champneys, including famous Virginia Woolf [Bell], his grand-granddaughter, and others within the ancestry who had recorded biographic accounts of their forefather in their fashion taking little care to separate facts from fictions. It is mostly from them we knew about Cavalier Antoine De L’Etang, the handsome young man of noble origin, – as a Page of Honour to the Dauphine Marie Antoinette, – as an officer of the King’s Guard du Corps, – as the Superintendent of the Royal Stud, and – as a Chevalier of the Royal and Military Order of St. Louis.

In addition to such honourable attainment, they keep mentioning also of a secret love between Queen Antoinette and her formerly Pageboy, De L’Etang, that costed his banishment for a lifetime. Marie Antoinette was said to be scandalized disproportionately for political gain and there might have been many love stories in circulation. The Swedish count, Hans Axel von Fersen (1755-1810) referred to earlier is named as her lover [Chateau/ Alex]. De L’Etang’s love affair so far goes missing from records.

RETROSPECTION

To curate the account of Antoine De L’Etang we need to find each of the above claims, which decorated him as an adorable romantic hero, in historical proximity for closer review.

PAGE OF HONOR TO THE DAUPHINE ANTOINETTE

Since Louis XIV settled in Versailles the royal household expanded over the years. He alone employed as many as 208 pageboys and further 24 who ranked a bit over the common pageboy. We may well expect that Louis XV engaged Antoine De L’Etang, out of the select few, a Page of Honour to his daughter-in-law, Dauphine Marie Antoinette as soon as she entered the royal house of Versailles.

A Page of Honour traditionally hailed from a noble family. Typically, he would receive training in many skills such as horse riding, falconry, lancing etc. all that was part of the masculine aristocracy in medieval Europe. Generally, upon reaching around fourteen years of age, if the Page was deemed appropriately trained, he was promoted to the position of a squire. A squire then went on to serve a knight, both on and off the battlefield [Medieval Chronicles] De L’Etang started in the position of a Page of Honour to the Dauphine when he was already 14 and continued for another four years before got promoted in 1774 to a Bodyguard of the King’s Guard du Corps in the Company of Jean de Noailles (1739-1824) at the age of eighteen.

BODYGUARD OF THE KING’S GUARD DU CORPS

De L’Etang was known to have been admitted in Garde du Corp of the King Louis XIV. ‘When he was too old to remain her Page he became an officer of her husband’s bodyguard. [Spooner] The French online directory, Officiers Généraux De L’Armée De Terre et des Services, that includes no reference to Antoine De L’Etang, discloses the existence of another L’Etang, named Dupont de L’Etang Pierre (1765-1840), whose year of death corresponds with that of Antoine de L’Etang. Dupont who was a ‘Général de Division’, fought in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and other wars – a war hero in French military history. [Etienne]

The Garde du Corps was exclusively aristocratic, in contrast to other units of the Royal Household, drawn from families with appropriate social backgrounds; as such they were noted for their courtly manners but less so for their military skills and professionalism. Individual courtier guardsmen stationed at Versailles were not subject to regular training beyond ceremonial drill, and extended periods of leave from duty were common. A critical report, dated 1775, concluded that the Body Guard and other “distinguished units with their own privileges are always very expensive – fight less than line troops, are usually badly disciplined and badly trained, and are always very embarrassing on campaign”. [Mansel]

Through his Garde de Corps training, the tall and handsome Frenchman, Antoine De L’Etang, developed an adorable personality with a courtier’s polished manners, well-groomed in aristocratic fashion and mannerism, somewhat less disciplined and less professional in martial arts, and was more inclined to showmanship.

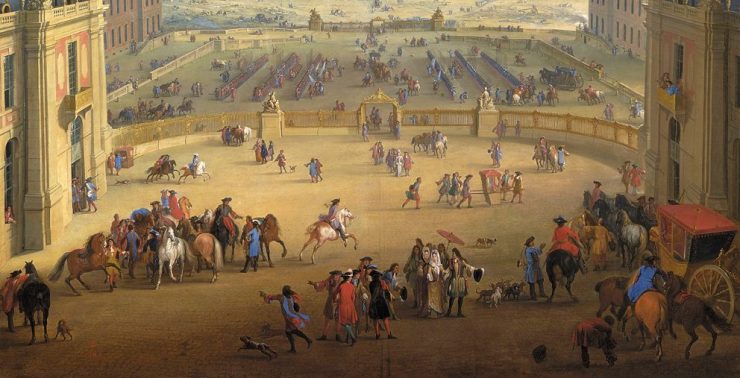

SUPERINTENDENT OF OF THE ROYAL STUDS, VERSAILLES

That Antoine De L’Etang was given charge of the Royal Stud, was what Roberdeau and other writers believed without giving much thought about the enormity and complexity of the Royal Stable of Versailles, a twin establishment comprising ‘Great Stables’, and “Small Stables’ built-in with incredible architecture enclosing the Place d’Arm. Nearly 1,500 men worked there, including squires, pages, coachmen, postilions, footmen, lads, messengers, chair bearers, stablemen, blacksmiths, saddlers, tack manufacturers, chaplains, musicians and horse surgeons, creating a constant hive of activity. It was a world unto itself. During the 18th century, more than 2,000 horses at any one time were stabled in the Royal Stables.

The Great Stables were managed by the Grand Equerry of France, while the Small Stables were placed under the orders of the First Equerry. The Grand Equerry was an important royal officer who was in charge of all the king’s horses and the equestrian academies, and he also looked after the horses ridden by the king and princes. These saddle horses were perfectly trained for hunting and war. The First Equerry was in charge more generally of all the other mounts and the coach horses … [Chateau de Versailles].

The name of Antoine De L’Etang was not found in any records of the Royal Stables accessible to us. This may be because of our limitations in accessing or because little resources are available to fall upon. What appears to be more realistic is that, contrary to the popular view, the superintendence of Royal Stud was too high a responsibility to be attainable for a boy in his early twenties with no adequate training other than what he picked up at Garde du Corps an institution ‘noted for their courtly manners but less so for their military skills and professionalism’. [Chateau – Stable]

CHEVALIER OF THE ROYAL AND MILITARY ORDER OF ST. LOUIS.

The Royal and Military Order of St. Louis, one of the most enviable French accolades, Antoine De L’Etang was said to have earned. Marquess Hastings, Evans Cotton and whoever else said it, must have good reasons to believe that the formerly Garde du Corps of Louis XVI had received the historic medal as they could see him wear the decoration, and so we do see in his painted portrait in a pendant reproduced here. ‘Seeing is believing’ is in human nature. Still, at times we cannot help questioning about the veracity of verisimilitudinous things when found conflicting with their context. Looking back to the history of the Saint-Louis Order and reviewing the circumstantial advantages/ disadvantages of Chevalier De L’Etang to receive the honour, should strike our mind with, in fact, not one but many a question:

Until the death of Louis XIV, the medal was awarded to outstanding officers only, but it gradually came to be an award that most officers would receive during their career. During the French Revolution, a decree changed the name to ‘décoration militaire’, and was subsequently withdrawn on 15 October 1792. Louis XVIII reinstated the Order of Saint Louis, using it to award officers of the Royal and Imperial armies alike. In 1830 the Order was abolished.

De L’Etang, besides a Roman Catholic by faith and enjoying the untold advantage of his being of noble birth, might not have qualifications to match the mandatory requirements, unless his experience in the Garde du Corps took care of the clause: ‘at least ten years’ service as a commissioned officer in the Army or Navy’, and if it was also okay for De L’Etang, who had left the French Army for good in 1795 to receive the award in 1814 which the ‘officers should receive during their career’. Nor that we know of something extraordinary De L’Etang did to warrant an order of chivalry as an ‘Outstanding Officer’. All these misgivings can be set at rest by reinterpreting the terms of legitimacy, but there remains a more fundamental question of propriety; that is, how happy and proud the French authority could feel in awarding a national order of chivalry, like the Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis, to a candidate banished for unfaithful acts, and who changed his loyalty to their rival power EIC?

It is interesting to note that among the three ranks of the Order of St Louis, namely, Chevalier, Commandeur and Grand-Croix, De L’Etang allegedly belonged to the rank of Chevaliers who was supposed to wear the badge suspended from a ribbon on the breast, whereas, De L’Etang used to wear the badge with ribbon on the left breast the specified way a Grand-Croix should do according to the norms. This deviation speaks of De L’Etang’s aspiration for an image larger than life.

The official records show that there was another De L’Etang, named Pierre-Antoine, comte Dupont de l’Étang (1765–1840), a French general of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, who had earned a Commandeur of the Order of St Louis. [Mazas. V.2] We also know from the same source that the name of Antoine De L’Etang, the captain of sepahi, posted in Pondicherry was in the preliminary list but left out finally being ignored as an out-stationed candidate. [Mazas. V.3 ]

END NOTES

History happens. One cannot make history, other than in a literary sense. In our collective endeavour to understand the past, the problem of weeding out extraneous data is always a critical one. The overzealous writers allow infiltrating superfluous data, typically, in hero-worshipping or narrating matters of pride and prejudices. Most of the biographical accounts of Chevalier Antoine De L’Etang likewise contain wishful thoughts, instead of verifiable facts, that baffle attempts to recognize the real man behind the painted mask.

In our study, we noticed De L’Etang’s weakness for money and fame that sometimes obliged him to act meanly as he did with Soubise. It was Soubise, who already inaugurated his new institution, the ‘Calcutta Repository’, introduced De L’Etang to Blechynden as his new partner. The ‘new partner’, however, never hesitated to put him in prison for debt, and disinclined to pay him the half of the business profit as per term. De L’Etang finally bought the Repository in 1797 just a few months before Soubise died. The Repository was then renamed as ‘Mr A De L’etang’s Repository in Calcutta’. The memory of its founder was pushed back behind the scene as a mere ‘unfortunate man’. [Blechynden] Yet, contrary to such inconsiderate dealings with Soubise, De L’Etang had the story to his credit of saving the life of an unknown Maxwell, belonging to the enemy camp, out of compassion. It was, indeed, a magnanimous gesture, which De L’Etang never felt for Soubise, the Black Caribbean. For a noble aristocrat of the 18th century France, It was not unlikely to have a streak of racism in his character. His genteel countenance and refined manners might have triggered a superiority complex, which could be a reason also for his having interpersonal relationship issues in his workplaces in Calcutta and Oudh, as some chroniclers hinted.

Antoine De L’Etang had the talents and opportunities to come into prominence as – a lovable man of the town. He was known to Calcutta society in its varied grades, from the Governor to horse-dealers. His humble official position could not deter him to hobnobbing with the high-level officials in parades and parties, which is quite apparent from the incidences of negotiated marriages between his beautiful daughters and some worthy sons of famous British families. We are also aware of his making “a large number of friends among the riding-public—and nearly all Calcutta men then as now were riders” [Blechenden] We had no luck to look into the details of his interactions with the society giving more exposure to the life of Calcutta of his time truthfully instead of having been bewildered with superfluous debatable attributions to a tragic hero.

REFERENCE

Asiatic Annual Register. 1808. “Bengal Occurrences.,” 1808. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=aXVfAAAAcAAJ&pg=RA1-PA55&lpg=RA1-PA55&dq=Nov.+1807+Bengal+Occurrences&source=bl&ots=sfCSfqIRHI&sig=ACfU3U1wasdVYT0HMIewYGpplVupUpS0vw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjglOPD-r_sAhWYxzgGHQ2pD2MQ6AEwAnoECAMQAg#v=onepage&q=etang&f=f.

Baillie, Alexander Charles. 2017. Call of Empire: From the Highlands to Hindostan. Chicago: McGill-Queen’s U.P. https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Call_of_Empire.html?id=uMw2DwAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y.

Bell, Quentin. 1974. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Randon House. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=9hYqDwAAQBAJ.

Blechynden, Kathleen. n.d. “The Chevalier De L’Etang.” East and West. https://archive.org/details/historicalrecord00hodsrich/page/76/mode/2up?q=etang.

Calcutta Gazette, The. n.d. “Reports Dated February 19th, 1795, July 5, 1798, 25th August, 1798; August 30, 1798.” Calcutta. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/calcutta-gazette.

Chateau de Versailles. n.d. “Royal Stable.” Official Website. Accessed October 30, 2020. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/estate/royal-stables.

Chateau de Versailles. n.d. “Alex Von Fersen (1755-1810).” Official Website. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/axel-von-fersen.

Chateau de Versailles. The official Palace of Versailles. n.d. “Royal Stable.” Accessed October 30, 2020. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/estate/royal-stables.

Cohen, Ashley. 2020. “Julious Soubise in India.” In Britain’s Black Past; Edi by Gretchen H Gerzinz. Liverpool,: Piverpool U.P. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ojfWDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA215&lpg=PA215&dq=julius+soubise+britain%27s+black+past&source=bl&ots=If5xkJmj-y&sig=ACfU3U3_7EEHLEjLsSShYgWW59kbgjMFcg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjU3MD0mrPoAhXzwTgGHfayC6cQ6AEwBnoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=julius.

Cotton, Evans. 1907. Calcutta, Old and New: A Historical & Descriptive Handbook to the City. Calcutta: Newman. https://archive.org/details/calcuttaoldandn00cottgoog.

Covington, Richard. n.d. “Marie Antoinette.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/marie-antoinette-134629573/.

Dalrymple-Champneys, Weldon. 1978. “From Royal Page to Veterinary Officer. A Short Account of the Life of Pierre Ambroise Antoine de l’Etang, Chevalier de St Louis, by His Great-Great-Grandson, Sir Weldon Dalrymple-Champneys, Bt.” The Veterinary Record 103. 265. https://europepmc.org/article/med/362692.

Dutta, Sutapa. 2017. British Women Missionaries in Bengal, 1793–1861. London: Anthem Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=sE5GDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Etienne, Delphine et Alain Guena. 2010. Officiers Généraux De L’Armée De Terre et Des Services: Ancien Regime – 2010. Vincennes: Bureau des archives historiques de l’armée de Terre.

France. Archives Nationales d’Outre-mer. n.d. “Personnel Colonial Moderne (FIN XVIIIE-XIXE S). Antoine De L’Etang.” http://anom.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/ark:/61561/fg469ifgciy.

Hodson, Vernon Charles Paget. 1910. Historical Records of the Governor-General’s Body Guard. London: Thacker. https://archive.org/details/historicalrecord00hodsrich/page/76/mode/2up?q=etang.

India Office. 1811. “Records: Bengal Pol. 4 Sep 1811 E/4/671.” London. http://searcharchives.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/dlDisplay.do?docId=IAMS041-000738591&fn=permalink&vid=IAMS_VU2+.

India Office. 1814. “Board of the Commissioners of the Affairs of India Records: Ref. IOr/F/4/312/7127. Date: Aug 1814-Aug 1815.” London. http://searcharchives.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/dlDisplay.do?vid=IAMS_VU2&docId=IAMS041-000740179&fn=permalink.

Jehaes, Els, and ors. 1998. “Mitochondrial DNA Analysis on Remains of a Putative Son of Louis XVI, King of France and Marie-Antoinette.” European Journal of Human Genetics 6(4). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13505349_Mitochondrial_DNA_analysis_on_remains_of_a_putative_son_of_Louis_XVI_King_of_France_and_Marie-Antoinette.

Mansel, Philip. 1984. Pillars of Monarchy: An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards, 1400-1984. London: Quartet.

Mazas, A. and T. Anne. n.d. “Histoire De L’Ordre Royal & Militaire De Saint-Louis d’Après “Histoire De L’Ordre Royal & Militaire De Saint-Louis, Depuis Son Institution En 1693 Jusqu’En 1830.” https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=fr&u=http://www.memodoc.com/article_ordre_st_louis.htm&prev=search&pto=aue.

Mazas, Alex. 1861. Histoire de L’Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis; . Depuis Son Institution En 1693 Jusqu’en 1830; Tom 2. Paris: Didot. https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Histoire_de_L_ordre_royal_et_militaire_d.html?id=MVKbEsdpuAoC&redir_esc=y.

Mazas, Alex. 1861. Histoire de L’Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis; . Depuis Son Institution En 1693 Jusqu’en 1830; Tom 3. Paris: Didot. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=yugTigqHlWYC&q=etang#v=snippet&q=etang&f=false.

Medieval Chronicles. 2000. “Discover Our Medieval Past in Hundreds of Factual, Informative and Easy to Understand Articles.” 2000. https://www.medievalchronicles.com/.

Puronokolkata: Calcutta as she was. 2020. “Julius Soubise (1757-1798).” 14 July 2020. 2020. https://puronokolkata.com/2020/07/14/julius-soubise-a-magnificent-horseman-in-18th-century-calcutta/.

Roberdeau, Henry. 1825. “Accounts of Life in Calcutta in 1805. (Editorial Notes).” Bengal Past And Present 29.

Rootweb. n.d. “The Pattle Family Tree. Ambrose Pierre Antoine, Chevalier de L’Etang.” http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~pattle/genealogy/Chev.de l%27Etang.htm%0A.

Spooner, Deborah (. 2006. “Biography for Ambroise Pierre Antoine de l’Etang (1757-1840).” Wikitree. 2006. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/De_l%27Etang-2.

Velde, Francois. n.d. “The Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis.” https://www.heraldica.org/topics/france/frorders.htm#st-louis.

Vibart, Henry Meredith. 1881. The Military History of the Madras Engineers and Pioneers, from 1743 up to the Present Time. London: Allen. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL23319477M/The_military_history_of_the_Madras_engineers_and_pioneers_from_1743_up_to_the_present_time..

<p value="<amp-fit-text layout="fixed-height" min-font-size="6" max-font-size="72" height="80">

Dear Ajantrik — in tune with your – Nom de Plume — your beautiful blog on – Antoin d’ La Etang — a fascinating story — which stitches together colourful lives and absorbing scenes of events that happened centuries back in strangely divers places like Paris, London, Vienna , Madras, Pondicherry and Calcutta — made an absorbing piece of masterly narrative. Your intelligence and passion to bring forth with utmost care of historical credulity — the Dowager queen of today”s Kolkata — to a

flirting captivating dame in her late teens i.e. Colonial Calcutta of late 18th. century — is a unique and marvelous literary piece. Meilleurs voeux de Pondichéry du 21e siècle — nirmalyada

LikeLike

Dear Dr. Majumdar,

Your comments with rich observations always come to me as lasting inspiration. Thank you also for the kind words of appreciations. The last two posts about the two magnificent men are indeed most engaging in their own right, because of the extraordinary happenings in their lives. It is a pity, a large proportion of information still remains inaccessible to get full exposure of the social and cultural networks they belong to. I failed miserably to identify relationships with the local inhabitants beyond the Europeans and Anglo-Indian circles. Believe, some researchers will take interest to further the investigative work. Wish you very best

LikeLike

Your restoration of Cavalier Antoine de I’Etang’s character and period is as dramatically resurrected as that of Julius Soubise. And i cannot thank you enough for your passion for referencing to authenticate the details for documenting the past.

Through your discerning portrayal we get the glimpse of his persona which is a

fine blend of French aristocratic pedigree in the English-influenced circumstances, professional wisdom of an era gone by, charismatic flamboyance with an almost idiosyncratic streak of arrogance and a enchanting presence that touches the heart.

I, particularly noted the classically tone and gracefully benign words with which he introduces himself and presents his book on Farriery to Major General Floyd, the fascimile copy of which you have shown us.

Thank you, once again, for holding up, so endearingly, a style and substance that was all but lost.

LikeLike

Dear Shubhrendu,

Thank you so much Shubrendu for your warm appreciation, and your sustained interest in reading puronokolkata. I am more than glad to know your reactions on reading about De L’Etang, which discloses almost the same kind of sentiments I developed in course of my investigation. We could not reject him for his wrongdoings. The real man behind the avatar finally came out and warranted an in-depth review of De L’Etang and his time, which I believe some scholars will take up sooner or later. Warm wishes

LikeLike