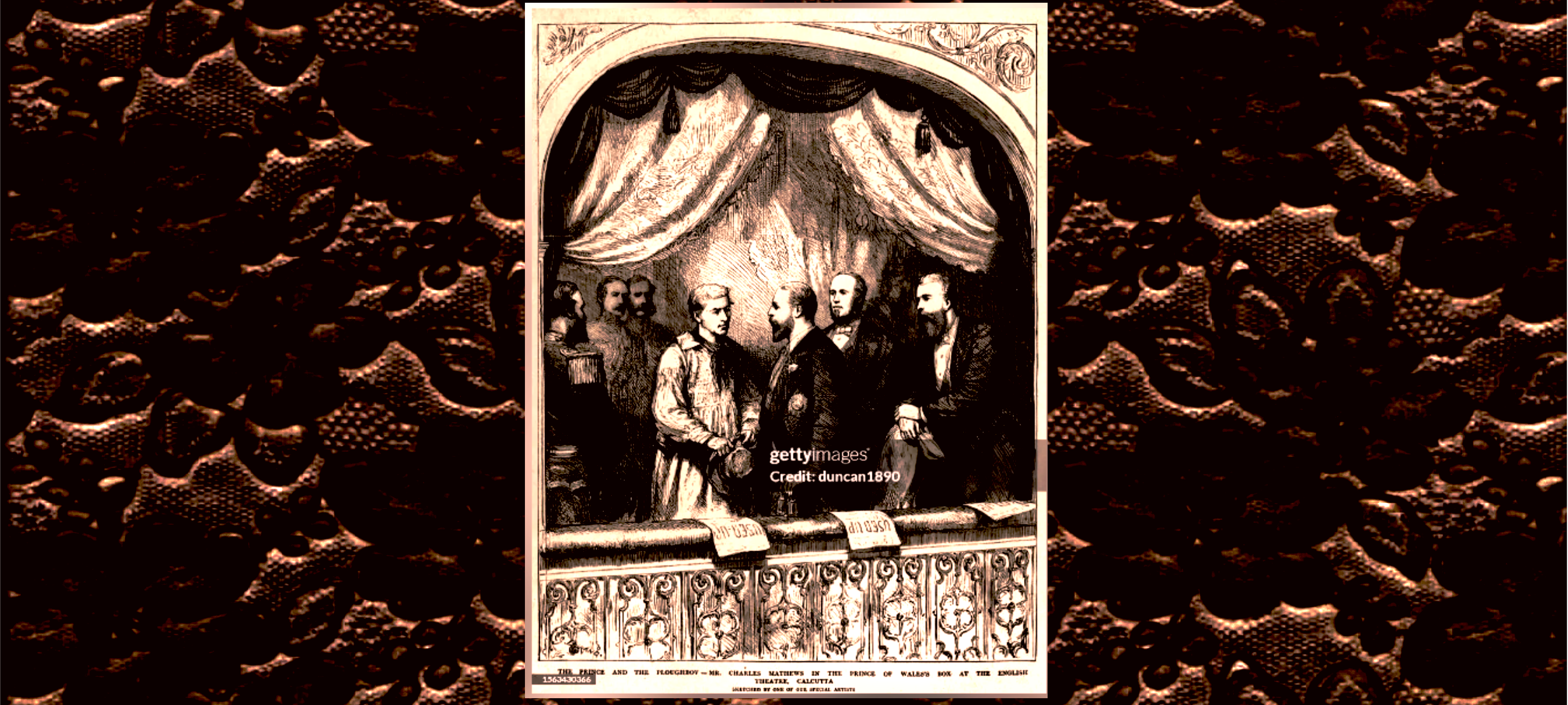

Prince of Wales’s Box at the English Theatre. Calcutta. 1875. Courtesy Getty’s

Backdrop

British ex-pats built ‘Town Calcutta’ replicating London to continue to live in an exclusive English style, shutting out the natives of the land. It may appear a hard saying, yet the fact remains that, even for the natives, Calcutta was an artificial place of residence [Firminger]. The Britishers were proudly possessive of their new home Town Calcutta, and anxious to preserve the British cultural conventions that endorsed their extravagant lifestyle.

The first English theatre, The Playhouse created in c1754 was gunned down within a couple of years of its existence in 1756 by the army of Shiraj leaving behind no memory of its theatricals if ever performed. The image of the Playhouse that Thomas Daniel depicted in the ruins of the Old Fort in 1786 happened to be the only document to prove the historicity of the 1st Playhouse. The East India Company found it more convenient to convert it into a chapel rather than to restore the playhouse to serve as an icon of British culture.

Calcutta Theatre. 1776-1795

The famous Calcutta Theatre jubilantly opened in 1776 after a lull of two decades since the first English playhouse was destroyed. Under Government patronage, Calcutta Theatre was founded by Lieutenant Colonel George Williamson, an auctioneer. During its long life of thirty-three years, the theatre entertained the English settlers with classical and some contemporary dramas to their taste besides providing them with a lavish space for socialization.

The quality of the theatricals on the stage of Calcutta Theatre was found above board and often excellent compared to the London playhouses. Mrs Fay in March 1781 admired ‘characters supported in a manner that would not disgrace any European stage’ [Fay]. After a glorious period of two decades, Calcutta Theatre encountered a changing audience who liked to be amused with fun and entertainment rather than contented with the delight of histrionic art. The Theatre struggled to survive by lowering its standards to the popular demands by staging farce and musicals instead of haute dramas.

Since the early 1790s, we find in the Bills of Affairs a shift in the theatrical genres when comedies were being substituted with farces and tragedies with melodramas. We may notice there that at the beginning of 1789, on the 22nd of January, when such a ‘uniformly well-acted play of The School for Lovers was staged there were very few in the thinly populated auditorium to appreciate. Before the end of the year, the Indian drama ‘Sakuntolla’ or the Fatal Ring, provided by its translator Sir William Jones, was played liberally. The play was a very different kind from the popular English hilarious dramas and comic operas such as The Road to Ruin, or The Country Girl. The Calcutta spectators rushed to witness those farces and melodramas all the time until Calcutta Theatre finally dropped its curtain. Hannah Cowley’s popular and enduring comedy, The Belle’s Stratagem, first produced at Covent Garden in 1780 was performed a hundred and eighteen times in London before the end of the century [Finberg]. There was not much difference in the mood of the theatregoers of London and Calcutta toward the end of the eighteenth century. As an instance, Calcutta Theatre staged the farce of Barnaby Brittle, in 1795 with a new musical entertainment called Rule Britannia to which William Carey lamented ‘our ancestors crowded to see’ [Carey].

As for the performing artists, Calcutta Theatre was fortunate to maintain a democratic environment in the sphere of dramatic management despite its being a hardcore racist institution. The same institution that burnt the Bengally Theatre of Gerasim Lebedev in 1795, permitted the anti-racist fierce critic of Hastings, Augustus Hicky to play the role of Desdemona on its stage against Julius Soubise a black Afro-British in the role of Othello, as reported in Bengal Gazette, Dec. 9th-12th 1780 [Cohen].

It was for their self-satisfaction, that the theatre enthusiasts gathered together in Calcutta Theatre to act on its stage free of charge. There were no steadfast rules for binding the amateurs together by defining their roles and privileges. Instead what they had in common was a spirit of the corp and an incredibly classless way of interaction on the stage forgetting one’s official ranking and social status even in a regimental political environment under the regime of illiberal Lord Cornwallis. Despite their best efforts, the amateurs often failed to play their roles well enough because many lacked talent and prework. The induction of some paid lady artists never improved the overall amateurish way of performance in the Theatre.

The Theatre lived a long life serving ‘as a tool of sociability’ balancing power relations between the patrons, performers, and spectators [Saha]. The two different causes of the Theatre’s downfall have been identified by James Long and other historians [Long]. The first one was the marked displeasure of Marquis Cornwallis against the participation of a Government servant in theatricals, and the other was the unfashionable locale of the Theatre, as Calcutta was then ‘moving out of town’ towards Chowringhee.

The celebrated institution that once charmed the Calcutta elites with many a great dramatic presentation, seems to have had some more deep-rooted sociological issue than administrative apathy, or the locational disadvantage, as Long suggested. The Calcutta Theatre, an out-and-out English theatre, was established to be run by the English for the theatre-loving English. This class happened to become proportionately fewer against the growing section of the whites comprising English, European and Eurasian who cared little for histrionics and instead took to getting amused with mundane entertainments. The changing demand pattern of the Calcutta audience alone may explain the slow death of the Calcutta Theatre when it was increasingly being used as an auction house or a public meeting place. It must be a gruesome phase that the Theatre had to pass through with the kind of awkward and erratic functionalities it was never designed for. The apathetic guardians, as well as the uninitiated audience, ultimately obliged Calcutta Theatre to bid adieu virtually about five years before it was auctioned in 1795.

Calcutta Void of Theatres 1789-1813

The vacuum created after the closure of Calcutta Theatre lasted till Chowringhee Theatre made its appearance in 1813 about a year before Calcutta’s Town Hall was erected on the site of a house in which Justice Hyde lived and was completed in 1814, for Rs 7 lakhs [Goode]. The majestic Hall was perfectly designed to suit dozens of different public events except operas and theatres – which were lamentably overlooked by the civil authorities. It is interesting to note that after a long while, in 1866, the management of the Town Hall had to face quite an embarrassment while it was required to house the first shows of Augusto Cagli’s Italian Opera despite its serious architectural limitations consequent upon the initial blunder of not including Opera and Theatre in the ‘requirement plan’ of the building [Rocha].

During the barren period marked by the absence of any public theatre, the British expatriates hailed the touring operatic and theatrical companies. The repertoire of the different touring companies speaks more of crowd-pleasing dramas, burlesques, and extravaganzas. Shakespearean plays were staged because they were fashionable. Calcutta elite society cared less for serious themes but the entertaining ones and did not mind a little vulgar or even a racy burlesque if that boosted the spirit of the theatregoers. The huge popularity of Dave Carsen’s pantomime and burlesque shows speaks rather loudly about what the Anglo-European community wanted in the name of ‘theatre’. The loss of credibility of theatre as the British cultural icon discloses the conflicting trends of the British administrative strategy toward public theatre. The theatre to them was a ‘hallmark of British cultural supremacy‘ which they believed to be unfathomable for the native intelligentsia. The theatre was also an instrument for the British Raj to induce racism and imperialism.

In reality, the claim for cultural pre-eminence of the British ex-pats, barring a handful of scions of noble families, never had any nor cared for cultural refinement but remained complacent with the kind of plebeian melodramas, farces, and pantomimes. Despite their personal preferences, those who came to Calcutta during the height of the Raj governance came in to be a part of the machinery, or to exploit British rule. “Their imperial purpose, position, and attitudes transformed these British civil servants, military leaders, and wealthy traders into aristocrats in all but name. These pseudo-aristocrats sought the trappings of cultural authority” [Rocha].

Chowringhee Theatre. 1813-1839

Chowringhee Theatre has a unique place in the theatre history of colonial Calcutta for a double reason. It is the last English theatre of the English and the first English theatre of the non-English in Calcutta, divided by a fine timeline.

Chowringhee Theatre was founded on 25 November 1813 under Government patronage by the Amateur Dramatic Society headed by Dr Horace Hayman Wilson – an eminent British orientalist who at another time helped Prasanna Coomar Tagore’s Hindu Theatre (1831) by translating Sanskrit dramas. The committee was composed of Englishmen and Europeans of distinction who often took part voluntarily in stage performances. With memorable fanfare, graced by the Governors-General Lord Moira, Chowringhee Theatre was opened with high hopes but soon started experiencing dwindling public response. It was primarily the amateurish way of its performances that mattered. We appreciate that ‘the amateur shows were something to be thankful for, but all knew they were not good enough ‘. The customs officials, magistrates, journalists, and doctors could scarcely be expected to be taken seriously when they staged ambitious Shakespearean productions without caring much to learn his lines properly [Shaw]. The Theatre had a hard time pushing on with uncertain resources. In 1824, the management failed to meet a huge fund crunch. It was forced to close down the Theatre against the will of certain die-hard theatre enthusiasts who believed the sacrifice of Chowringhee Theatre should cause a hateful face loss for the entire Calcutta society. It was probably at this juncture many of the old guns including Dr Horace Wilson and George Chinnery parted with the Chowringhee Theatre for good.

The Theatre reopened with the support of a few resolute members who made a game plan to give it a new life by inducting some star attractions to regain its popularity. Instead of hiring some London artists, which would have been costlier and less secure, some local artists of excellence were looked for. Luckily they found Esther Leach, a brilliant rising star, at Dumdum Garrison Theatre. In former times, the dramatic performances at Dum Dum almost rivalled those of Chowringhee [Emma]. Lord Amherst, an ardent patron of both the theatre houses induced Mrs Esther Leach to join Chowringhee Theatre as its leading artist and the theatre director. To secure her stay in Calcutta he graciously got her spouse Sargent John Leach transferred to Fort William [Dasgupta]. Leach, regardless of her Anglo-Indian origin stepped into the inner circle of Chowringhee Theatre overriding its policy of racial discrimination. “Here Mrs Leach, the ‘Indian Siddons’, made her bow to a Calcutta audience as Lady Teazle on 27 July 1826. She was then barely seventeen, and for many years she continued to be the idol of the theatre-going public [Cotton]. The new management secured the services of other well-known artists as well. There was also some marked improvement behind the stage. Old debts were settled, the building repaired, and in no time Chowringhee Theatre became one of the star theatres in India and was in its zenith of fame during the years 1826-1832.

After 1832 the Theatre had a hard time once again. The overall economic and political situation in India was suddenly in turmoil in 1833 leaving the social and cultural life to a standstill. Despite its popularity, the theatre was never stable financially and became a liability to the owner. To escape its imminent crisis, Chowringhee Theatre was leased to an Italian Company at a nightly rent of Rs 100. After they failed to pay the high rent the theatre was leased to a French Company at Us. 50/- per night, which too began to fall in arrears every month. The proprietors, therefore, themselves tried their hand once again to boost ticket sales by reducing the prices to six rupees per box and rupees three for the pit. The scheme worked for a while but proved no good in the long run. The proprietors being unable to clear huge debts amounting to Rs 20,739 ultimately put up the Theatre for sale on the 15 August 1835. No White Towners came forward to save the icon of the British culture, but the native Prince Dwarkanath did so not for speculations but to save the theatrical culture in Calcutta. Prince Dwarkanath purchased the Theatre, its wardrobe, and appurtenances, paying Rs 30,000/, double the price of shares, and became a joint owner of the Theatre.

Liberalized Chowringhee Theatre 1835-1839

A new chapter of Chowringhee Theatre opened in its renovated house that could hold, going by William Prinsep’s note, about 800 persons in the boxes and 200 in the pit. Never before a theatre in India did welcome spectators of all skin shades. Like other enterprises of Dwarkanath, Chowringhee Theatre turned into an assimilationist institution free from racial prejudice. The re-established Theatre under new management was practically a novelty institution, radically different from its original state of being, that existed with a borrowed identity as it had none of its own and it walked the line with a burden of the past it inherited.

Dwarkanath delightfully accepted his role as an impresario. Amongst his friends who shared his delight, were the kindred souls dedicated to the cause of Chowringhee Theatre, like — Henry Meredith Parker, Joachim Hayward Stocqueler, Charles Metcalf Plowden, James Hume, William Prinsep, T.J. Taylor besides Captain Richardson. They all were collectively responsible for presenting the theatre as ‘a setting for social intercourse between the races’ [King]. The Chowringhee Theatre became a fervent hub where Calcutta elites would gather for chats or drinks. There were regulars like Prof. Richardson who often urged his Hindu College students, including the Derozians, to attend theatres and even occasionally supplied them with tickets. If any public theatre can ever boast of its connection with a galaxy of brilliant scholars, artists, and men of lead and light, belonging to the West, and having an intimate connection with the Indian people, it was the Chowringhee Theatre. [Dasgupta]

Apart from the direct influence of the performing English theatres in nineteenth-century Calcutta, there had been a conscious learning process introduced by some extraordinary schoolmasters like David Drumond and David Hare, for their students to acquire tastes and skills in theatrical arts and stage crafts. Half a dozen old schools were found to have theatricals in curricula. There the students themselves learn dramatics by playing a part on the stage. It may be noted that only in the early twentieth century the English educationists felt “There is a serious danger in the class-room, with textbooks open before us, of our forgetting what drama really means” and went on experimenting with teaching Shakespeare play way [The English Assoc.]. Shakespeare was taught in several venerable Calcutta schools since around 1817, much before it was accepted as a subject of higher study in Hindu College. In Hindu College, Shakespearean dramas were studied under great teachers like David Lester Richardson, C.H. Tawney, H.M. Percival, and Henry Louis Vivian Derozio. There was another teacher of European origin, Hermann Geoffroy – the adorable Headmaster of the Oriental Seminary, whose influence in acquiring a taste for histrionic art and love of drama amongst the Bengali students was much the same as that of Professors Horace Wilson and Captain Richardson did [Bayly]. Thereupon a new audience was born to appreciate English theatre and let it go a long way.

The abrupt tragic end of Chowringhee Theatre in a ghastly fire on 31 May 1839 sent a shockwave the next morning through the newspapers petrifying Calcutta denizens. Curiously, no one from the British-European community came forward to propose rebuilding the charred theatre house to bring Chowringhee Theatre back to life, as would have been expected.

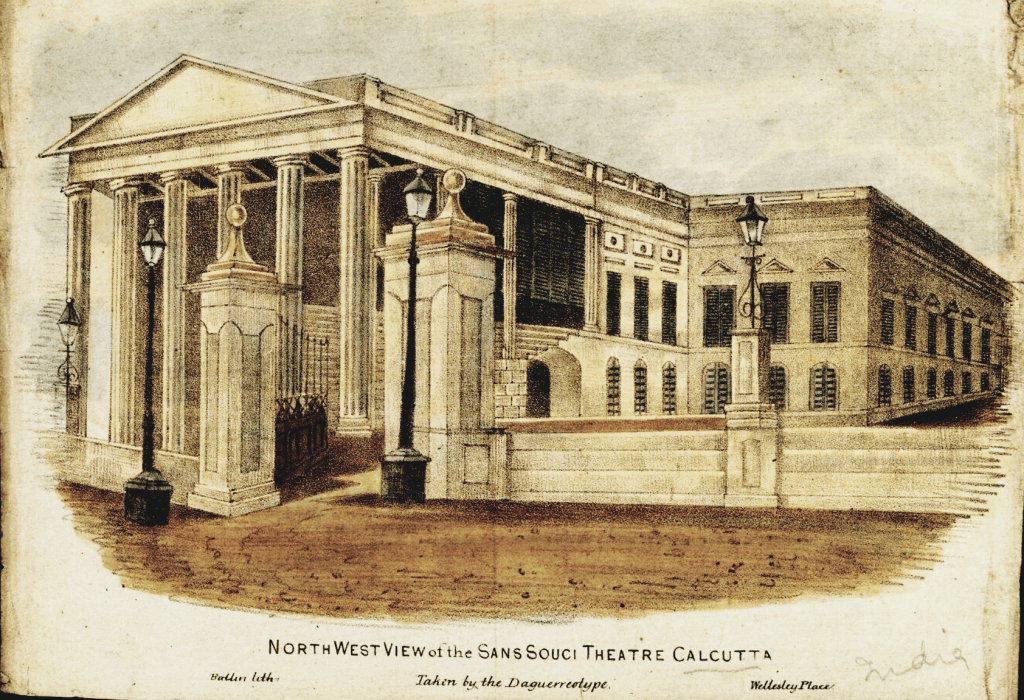

Sans Souci 1841-1849

The tragedy led to a short spell of uncertainty for Calcutta theatregoers until Mrs Leach returned from her London sojourn and started within months the Sans Souci, her new theatrical enterprise, at a transient venue in Government Place on the site where the Great Eastern Hotel stands now. The vacant floor was converted into an elegant theatre hall. It was a small but delightful interior made out following the design she made herself. The stage, the stage front, and the walls – all were decorated appropriately. There was also an orchestra pit. The auditorium accommodated 400 seats allocating 108 seats for stalls priced at Rupees 6 each, Box Rupees 5 each, and Upper Box Rs 4 each.

The success of Sans Souci was simply astonishing. Persons of all ranks, but chiefly of the upper class, crowded to the performances, which were twenty-five in number in six months. We are fortunate to find a candid review of the scenario of the auditorium at Government Place informing us how the characteristics of the audience were being changed rapidly. The British journalist, Emma Robert observed that that was the first time ‘parties of Hindostannee gentlemen beautifully clad in white muslin’ graced the auditorium. They prefer sitting nearest to the stage. The management obliged them with frequent performances of Macbeth and Othello as they liked tragedy most [Roberts]. The interior of the theatre hall proved soon too small for the growing audience, and it was resolved to attempt to raise a new theatre by subscription [Bengal].

In March 1841, Sans Souci was established in its building at no. 10 Park Street after operating for months from a transient accommodation at 10 Government Place East. Sans Souci was born a people’s theatre out of the dream of Mrs Esther Leach, a non-Briton theatre entrepreneur, and artiste, who ended the British legacy of English theatre in India almost single-handedly. Sans Souci provided the people of Calcutta with a far grander alternative stage open for all – a truly public institution free from racial, political, and economic differences like never before.

In favour of the Bengali audience, Miss Emily Eden – an overly critical English lady of everything native, following her visit to Sans Souci at Park Street, dropped a few kind words on 11 November 1841. She writes, “The house was over-full, and it must be a wonderful change to people who remember India ten years ago to see quantities of baboos, who could not get seats, standing on their benches reading their Shakspeare’s, and then looking off at the stage, and then applauding on the backs of their books. At least one-third of the audience were natives, who were hardly admitted to the theatre when first we came, and certainly did not understand what they saw (my emphasis). [Eden] This may be a perfect example of the way Emily and her British elitist fellows reacted to the emergence of the new class of Bengali audience with copies of Shakespeare in hand. It is worth noting that contrary to Emily’s beliefs, the presence of the Bengal audience in English theatre was welcomed a decade ago by the new management at Chowringhee Theatre. As suggested, it was at Chowringhee Theatre where a theatre-savvy audience was bred. Sans Souci welcomed the same audience, sensitive and receptive. Here, they were entertained with more theatres of excellence played by professional actors and actresses of London fame along with homegrown amateur talents mostly employees of the East India Company. The actresses, all professionals, were brought from England on contractual assignment — the principals being, Madame de Ligny, Mrs Deacle, Mrs Francis, Mrs Barry, and Miss Cowley. Among the amateurs was Mr H. W. Torrens, a versatile Bengal civilian, and his biographer, Mr James Hume, afterwards a Magistrate of Calcutta. Mr Stocqueler had also imported some actors from England. They were, to begin with, a Mr Barry and his wife. It was primarily an obligation of Mrs Leach to get the most out of the amateur actors to do their best to match her artistry and that of other professionals on the stage.

For two years Mrs Leach was nominally proprietress of the Sans Souci and thereafter became a member of the company on a liberal salary. The stage was henceforth managed by Mr James Barry, an accomplished performer of soubrette roles, whom Stocqueler had brought from Cambridge to join Sans Souci along with his actress wife. Towards the end of 1843, with the arrival of a professional leading artiste and stage manager, James Vining, Sans Souci entered a new epoch with Vining as its Director. His first appearance, as Shylock, was advertised as a gala night. It was, however, felt that his attractions could not safely be expected to stand without support from Mrs Esther Leach the famous actress of Calcutta comparable with the greatest London artist Mrs Siddon. So as was the Calcutta custom to stage a farce next to a Shakespearean play, The Handsome Husband was chosen to be played with Esther in her most popular role, that of ‘Mrs. Wyndham’, to doubly ensure a grand success of the gala night [Shaw].

The Aftermath 1843-1849

On that night of November 2, 1843, the teeming audience inside the Sans Souci hall had a little presentiment of how tragically the ‘gala’ was to end. The Merchant of Venice was well received and everything appeared all too good till the brutal anticlimax was struck suddenly when ‘The Handsome Husband’ started merrily. A fire struck Mrs Leach’s dress while waiting to enter the stage. She was instantly thrown down and the flames extinguished, but not before she had been severely burnt. Despite the assurance of Dr O’Shaughnessy and two other attending doctors that there was no life-threatening danger, Leach died at the age of 34 years on the 14th of November, 1843 probably because of a moral breakdown. The old records kept in Bishop’s House tell us that it was a triangle-shaped grave covered with weeds in plot “E” number 49, where eternally rests the actress ‘first favourite, adored by all Calcutta’ [Shaw].

For the benefit of the children of Mrs Leach, the proprietress, Madame Nina Baxter, gave up the house on November 22, but with little success. A subscription list on their behalf was opened by Mr T. P. Morrell, a Calcutta merchant, one of the four executors under the will another being Babu Moti Lai Seal. The subscribers included many Bengali as well as Esther’s European admirers including Sir Lawrence Peel who donated a large sum. [Madge] Esther was considered an elfin spirit that seemed to bring success to any theatre she joined and to take it away when she left. [Shaw] After her death, the fortunes of Sans Souci steadily declined: James Vining packed up and left for England after playing only three leading roles. The standard of production and performance started to deteriorate. Mrs Ormonde, ‘a noted pantomimist in Cambridge’ arrived from England and died of cholera within weeks. [Shaw] The proprietress next leased out the Sans Souci for three months to ‘La Companie Française de Batavia’ – the last opera company to come to Calcutta. The last regular performance, ‘Othello’, enacted for Madame Baxter’s benefit, took place on April 24, 1844 [Madge]. It may be the same day or another day in the same week when the professional members of the theatre took possession of the building for one night for a special benefit to raise their arrears of salary [Shaw]. As time went on, the playhouse remained closed for increasingly longer intervals, till finally wound up with an announcement that an event of circus would take place next season.

After the doldrums of about three years, Sans Souci enlivened to a certain extent when James Barry took it over for the second time. Apart a dedicated artiste he was found a great mediator who ‘had always done his best to conciliate all parties connected with the theatre’. Barry was a fine gentleman. He had taken the charge of the dying institution when there was none to take her care. Barry, however, became notoriously famous overnight after producing Shakespeare’s Othello in 1844, with a native gentleman Baishnav Charan Auddy playing the Moor of Venice, against Mrs Anderson as Desdemona. The appearance of native Baishnav Charan in the challenging role of Shakespeare’s tragic hero with an English lady was greeted with words of applause and encouragement in contemporary papers. However, his shortcomings were also pointed out. Sangbad Pravakar mentions that Baishnava Charan Addy twice played the part of Othello with great credit on Aug. 17 and Sept. 12, 1848, respectively. [Dasgupta] The play attracted a huge crowd that posed problems for the city police to maintain law and order. The conformist Britishers spitefully smirked, ‘Barry and the Nigger will make a fortune.’ Some agitated civilians, and the soldiers, in particular, also made attempts without success to stop the shows. [Rocha] It is interesting to note that, long back in December 1780, Julius Soubise, a British-Caribbean black artiste, had acted Othello in the Calcutta Theatre with the famous Hickey of Bengal Gazette in the role of Desdemona. A favourite of Garrick, Soubise had charmed his audience at Calcutta Theatre in November 1780 with his gesture and elocution. Soubise and his Othello’s role was long forgotten and remains unnoticed by the eminent historians that Soubise and Baishnava Charan, the two Othellos, of different shades of black and both victims of racism, created history in Calcutta stage a century apart [Ajantrik].

Against all odds, Barry continued tenaciously to steer Sans Souci even after the theatre house was sold out in 1846 for Rs. 40,000 to Bishop Carew, the Vicar Apostolic of Bengal, who in 1847 founded there ‘the little college of St. John’ later in 1860 re-established as the St Xavier’s College by the Belgium Jesuits. [Catholic Encyclopedia]. Sans Souci survived for three more years beyond 1846 as a homeless institution infrequently functioning from Mr Barry’s residence at 14 Wellington Square. The last homegrown English theatre of importance was closed down on 21 May 1849 with the final departure of James Barry. The ending phase of Sans Souci had a special significance as it stretched the end of the English theatrical culture of Calcutta’s Englishmen for three years more.

Grand Opera House

In 1867, The Grand Opera House at Lindsay Street was founded by the Opera Committee for the show of the Italian opera represented by celebrated impresario Augusto Cagli. Soon the Opera House became a most stately cultural institution – a mainstay of Western civilization in Asia. After Cagli, the Opera House lived the rest of its long life in its struggle to maintain a world-class standard under the stewardship of many impresarios, the most important ones among them were Alessandro Massa and Captain Wyndham.

Alessandro Massa took over the office of impresario for the 1872-1873 session. He was aware of his limitations in meeting the demands of the local aficionado for first-rate Italian opera artists and repertoires. He was however honest in his efforts and did his best to present good Italian operas. Massa also made a few contributions to Calcutta’s orchestra by introducing some European instruments, like the clarinet and the horn. Massa had a small working committee of his own solely for liaising with the public. We are not sure whether it was Massa himself or his committee was responsible for inviting the Hindu National Theatre to stage their Bengali dramatic performances at the Grand Opera House during April 1873 for three nights. The young men of the Hindu National Theatre grabbed the opportunity to stage their modern plays of sociocultural significance, portraying life in Colonial Bengal before the spectators of the white town. In April 1873, the Hindu National Theatre staged at the Opera House: Sarmistha (Michael Madhusudan Dutt), Bidhaba Bibaha (Umesh Mitra), Kinchit Jalajog ((Jyotirindranath Tagore), Ekei Ki Bole Sabhyata (Michel Madhusudan Dutt) and four Pantomimes played by Ardhendu Mustafi. The engagement with the Hindu National Theatre proved to be a boon for the Opera House which had been desperately in need of money to survive, and for that, its British management forgot their racial animosity for a while.

Colonel Percy Wyndham was the first English Impresario of Calcutta operas appointed for the next opera session 1874-75. Wyndham could not do much to improve opera qualitatively but endeavoured effortlessly to popularise opera in the wider cross-sections of the Calcutta society, and thus to strengthen Calcutta operas financially. He decided to reach audiences beyond the white town up against the wishes of his patrons and the elite society. The Opera Committee increasingly disliked Wyndham for his radical actions hurting the Anglo-European sentiments. Toward the end of his tenure, Wyndham made a historic decision on his own to lease the Lindsay Street Opera House to the Bengali enterprise, Great National Opera Company (GNO). The GNO took advantage of showing Sati Ki Kalankini twice at the Opera House and also at Lewis’s Theatre Royal, Corinthian Theatre, and Belvedere Fairground.

The financial condition of the Grand Opera House never improved. After a decade of uncertainties, the Grand Opera House was leased to Mr William B English, an American impresario, for the 1875-1876 season. During his time, the opera house was known as the English Theatre. It was here that Charles Mathews on New Year’s night of 1876 played the part of Adonis Evergreen in My Awful Dad before King Edward the Seventh, then Prince of Wales [Cotton]. [See Banner atop]

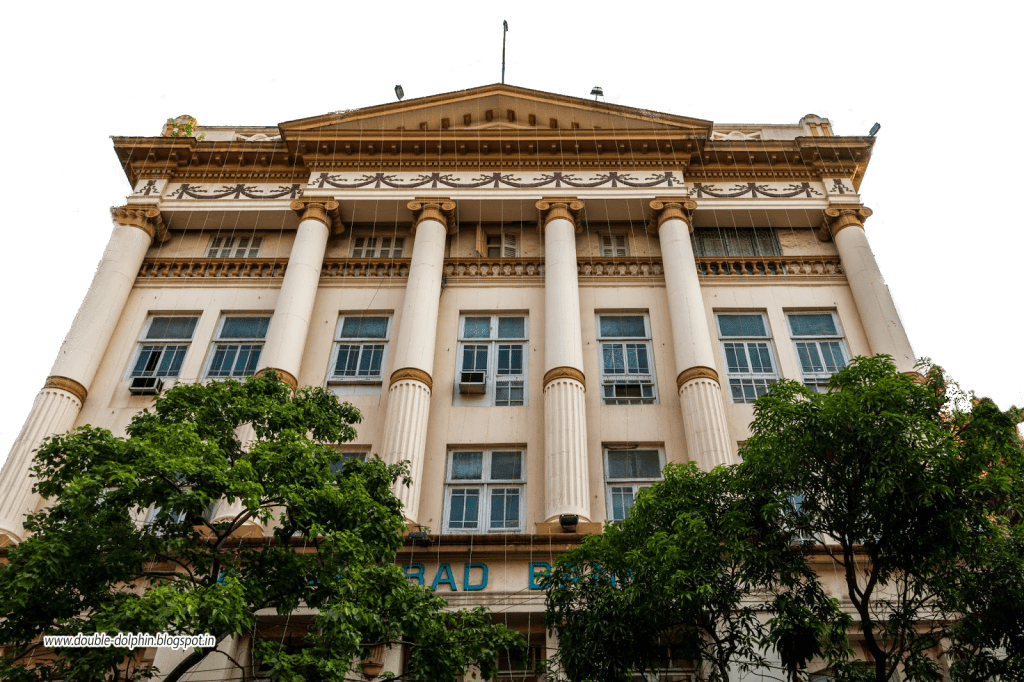

The Lindsay Street Opera House continued in its original form till 1906 when E.M. Cohen bought it. The house was extensively refurbished and reopened as the New Opera House, which was Calcutta’s premier vaudeville venue featuring a mixture of popular entertainments. After WWII, the theatre was converted into a cinema house named Globe Cinema.

Lewis’s Lyceum Theatre 1867-1876

The few English theatres, which came during the second half of the nineteenth century, were short-lived and inconsequential. A few English companies have no doubt given performances now and then to entertain the English and the Europeans, but the Bengalis had little concern for any [Dasgupta]. One of the reasons for such indifference was the irrelevance of the English plays in a socio-cultural context. In contrast, Bengalis found the dramas produced by firebrand dramatists like Dinabandhu Mitra, who spoke of their social and political experiences depicting highly charged colonial episodes of historic significance. As we understand at Sans Souci, like all other Calcutta’s English playhouses, the plays were selected from overseas ‘home products‘. Lewis’s theatres were no exceptions.

Two decades after Sans Souci, George Lewis and her famous actress wife Mrs Rose Lewis with their touring theatre troupe, Dramatic and Burlesque and Ballet Company, arrived in Calcutta in early September 1867 and immediately erected their Lyceum Theatre on the green of Maidan. Colligan mentions ‘Lewis’s theatre attracted many educated Bengalis, noted for their critical knowledge of Shakespeare’ [Colligan]. The Bengali theatregoers were deemed already mature enough to appreciate serious theatricals and critically reviewing performances. About one such review posted by a Bengali critic in a native paper on 11 January 1868, Times of India, Bombay Edition comments amusingly: “The tone is by no means complimentary to our theatrical troupes, as their performances are very severely handled, and in many respects, I must confess, with a certain degree of justice. Shakespeare has been studied by our Baboos in their educational courses at the universities and colleges, and they regard everything below Shakespeare as something scarcely worth notice.” [Dasgupta] This was a great compliment to the band of ‘baboos’ who had no interest in mediocre works, unlike their Anglo-European counterpart.

Lewis’s Lyceum, however, did much more for the Bengali theatregoers being acknowledgedly the chief influencer on the making of the first Bengali stage. The Lyceum Theatre served as the model for the first Bengali stage installed by the Great National on 31 December 1873. The Great National also adapted the English mode of performance, as played at the Theatre Royal, into the dramatic presentation they made for the Bengali audience.

The Lyceum and the Royal Theatres of George and Rose Lewis of Australia happened to be the last English theatres in Calcutta by overseas entrepreneurs. Before the Australian theatre company left Calcutta, the Bagbazarian boys, a small group of ‘creative minorities’, installed the first ever homegrown stage in English model dedicated to Bengali plays. The boys did wonders with the support and encouragement of Mrs Rose Lewis, the Stage Director of Lewis’s theatres and an ace artiste who highly impressed the young Bengali entrepreneurs.

Lewis’s Theatre’s affinity with Bengali theatricals grew on a professional basis. Mrs Lewis watched Girish playing Nimchand in Sadhabar Ekadasi in one of its repeat shows and considered his play a masterpiece [Utpal Dutta]. Very likely Mrs Lewis witnessed more Bengali dramas held in the native locality and certainly, she viewed on the stage of her own Theatre Royal the two Bengali plays: Sati Ki Kalankini and Kinchit Jalojog on 9 January 1875 enacted by the Great National Opera Company. Girish was full of appreciation for the style of acting in Lewis’s Theatre which he deemed to visit many times, even before he met Rose Lewis and befriended her. He advised others to see the English theatres at Lewise’s and the other playhouses to learn their way of performing on stage. Noti Binodini described how she was escorted to witness the English plays at the white town theatres. The Bengali stage not only borrowed from Lewise’s theatre its English architecture and mode of acting but also some theatre paraphernalia, like scene paintings, stage crafts, dressing and makeup, prompting, etc. [Binodini].

Lewis’s was different from other English theatres being purely a commercial and an independent profiteering house functioning outside the politico-cultural battleground that continued throughout the nineteenth century [Rocha]. It is most likely that the progressive group of the National Theatre learnt from the working of the Theatre Royal about the commercial side of theatre management and was encouraged to sell tickets to earn the running costs and not-for-profit, unlike the objective of Lewis’s.

Bengali Stage and the New Audience

While the native Indian audience was found full-grown with the necessary faculty for appreciating the high theatrical art through their education, the English and the European counterparts however remained uninitiated and incapable of appreciating theatres and operas other than the farces, melodramas, and satires of low taste. It would be an absurdity to think the British professional busy bees or the pampered public service officials devoted their time studying Shakespeare critically to appreciate his plays any better. Neither the English theatres of the English Raj had any stock of suitable dramas to make an attractive repertoire relevant to the society of English ex-pats in colonial Calcutta. It was, however, noticed that the Calcutta audience had well received some of the ‘native and to the manner born’ pieces written by European members. Captain Richardson, a literary man of recognized ability both in England and India, was said to have promised to write a five-act play expressly for the comedians of the Sans Souci. Malcolm assures us that ‘if the piece was at all written, never produced’ [Malcolm].

Sum-up

The irrelevance of the Calcutta repertoires obliged the Anglo-European audiences to distance themselves from their theatres. The separation of the theatre from its audience goes deep into the socio-political history of the British Raj pointing to the British cultural decadence in India – a matter of sociopolitical analysis, which is beyond the scope of this article. Whatever the reasons might be, it is evident historically that all the playhouses the English had established were desolated before dying of cultural poverty and the humiliation of being served as a circus venue, an auction house, or a venue for military or civic celebrations. English theatres of Calcutta were much abused by the English not because of their indifference but for attempting to redefine theatre perversely as a means of political gain. Unfortunately, the British realised their mistakes very late and had no way to come back but to bow out quietly from their last hold, the Chowringhee Theatre, in 1835, leaving its reign to a libertarian Committee headed by Dwarkanath Tagore the first and foremost interracial entrepreneur in colonial India. Calcutta’s prima donna Mrs Esther Leach, the daughter of an Indian mother, was the first non-British founder and owner of Sans Souci – an English theatre of the highest public esteem in 1839. Nearly two decades after Sans Souci had closed, the Australian theatrical troupe of George Lewis arrived in Calcutta, built their collapsible theatre Lyceum on the green of Maidan and thereafter constructed Theatre Royal next to the arcadia of the Grand Hotel, and then left Calcutta forever leaving behind a trailing memory of their theatrical mode and style as reflected on the Bengali stage built in renascent Calcutta.

Endnotes

Two eventualities marked the next phase of Calcutta’s theatre history. First, the isolation of the English Theatre having been rejected by the people and second, the silencing of the Bengali Stage by the legal instruments of the British Raj.

With the departure of the Lewises, the theatrical scenario suddenly met with the worst political adversity under the governance of Lord Northbrook who was determined to stall the democratic Great National Theatre from staging anything unpleasant to the British Government. The enactment of the Dramatic Performances Act of 1876 throttled the Great National Theatre as well as every other liberal native theatre in the country. In 1880, the Great National pitiably ended its glorious people-centric journey. With the foundation of Star Theatre in 1883 the Bengali stage was revived but as a commercial enterprise in every respect, run by professionals. By that time the English theatres were either closed down or lingering in isolation to get themselves transformed into the new generation picture-houses.

REFERENCE

- Ajantrik, ‘Sans Souci’, Puronokolkata.Com, 2022 https://puronokolkata.com/2022/09/15/sans-souci/

- Bayly, C. A, Recovering Liberties Indian Thought in the Age of Liberalism and Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011) https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Recovering_Liberties/0GLAWY6L8fIC?hl=en&gbpv=0

- Bengal and Agra Annual, ‘Description of Calcutta Part 3 . In Bengal and Agra Annual, 1841’’ (Calcutta: Rushton, 1841) https://archive.org/details/bengalandagraan00unkngoog/mode/2up

- Binodini Dasi, আমার কথা: Amar Katha O Onya-Onyo Rachona, ed. by Soumitra Acharya, Nirmalya and Chattopadyay (Calcutta: Subarnarekha, 1959) http://boibaree.blogspot.com/2018/09/blog-post_19.html

- Carey, William Henry, The Good Old Days of Honorable John Company from 1800 to 1858; Compiled from Newspapers and Other Publications; Vol.2 (Calcutta: Cambray, 1907) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.39169/page/n421

- Catholic Encyclopedia, ‘Archdiocese of Calcutta’, Newadvent.org https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03152a.htm

- Colligan, Mimi, Circus and Stage: The Theatrical Adventures of Rose Edouin and GBW Lewis (Melbourne: State Library Victoria, 2013)

- Cotton, Harry Evan, Calcutta, Old and New: A Historical & Descriptive Handbook to the City. (Calcutta: Newman, 1907) https://archive.org/details/calcuttaoldandn00cottgoog

- Dasgupta, Hemendranath, The Indian Stage; v.2 (Calcutta: M K Das Gupta, 1938) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.228124/mode/2up

- Dutta, Utpal, Girish Chandra Ghosh (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1992)

- Eden, Emily, Letters from India; v.2, Oxford University (London: Bentley, 1872), 2(2) https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(73)90259-7

- Fay, Emily, Original Letters from India of Mrs Emily Fay, ed. by Walter Kelly Firminger, New Editio (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1908) https://archive.org/details/originalletters00forsgoog

- Finberg, M. C. (2001). Eighteenth-century women dramatists. Oxford UP.

https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780192827296/page/n1/mode/2up

Firminger, W.K., Thacker’s Guide to Calcutta (Calcutta: Thacker Spink, 1906) https://archive.org/details/thackersguidetoc00firm/page/n8 - Goode, S W, Municipal Calcutta: Its Instituions in Their Origin & Growth (Edinburgh: Calcutta Corporation, 19916) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.180810

- King, Blair B, Partner in Empire: Dwarkanath Tagore and the Age of Enterprise in Eastern India (Berkeley: Berkeley U.P, 1976) https://archive.org/details/partnerinempired0000klin/page/160/mode/2up?q

- Long, Rev. James, ‘Calcutta in the Olden Time – Its People’, Calcutta Review, 35.Sep-Dec (1860), 164–227 https://doi.org/https://books.google.co.in/books?id=8DMYAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA164&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Madge, Elliot Walter, ‘Sans Souci’, Bengal Past and Present, 1 July 1904 (1904) https://ia601600.us.archive.org/0/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.459511/2015.459511.July–.pdf

- Malcolm, E. H, ‘Theatres in the British Colonies’, Colonial Magazine and Commercial Maritime Journal, 3. May-Aug (1843), 194–203 https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Colonial_Magazine_and_Commercial_maritim/SxtEAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Mrs.+Deacle+1840+english+actress&pg=PA195&printsec=frontcover%0A%0A%0A%0A

- Roberts, Emma, Scenes and Characteristics of Hindostan with Sketches of Anglo-Indian Society; Vol.3, Allen (London: Allen, 1835), v.3 https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Scenes_and_Characteristics_of_Hindostan/lcBFAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

- Rocha, Esmeralda, ‘Imperial Opera : The Nexus between Opera and Imperialism in Victorian’, 2012 https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/imperial-opera-the-nexus-between-opera-and-imperialism-in-victori

- Saha, Sharmistha, Theatre and National Identity in Colonial India Formation of a Community through Cultural Practice (Singapore: Springer, 2018) <https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Theatre_and_National_Identity_in_Colonia/qw92DwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=English+and+the+colonized+population’s+elite+found+‘theatre’+as+just+another+tool+of+sociability&pg=PA51&printsec=f

- The English Association, The Teaching of English in Schools (Leaflet No. 7, 1908), p2 https://www.academia.edu/22169766/A_HISTORY_OF_THE_TEACHING_OF_SHAKESPEARE_IN_ENGLAND

Discover more from PURONOKOLKATA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.