The home of the National Theatre Society on the first floor of the magnificent pleasure house, Bardwari Baithakkhana on the River Ganges, Babu Russick Neogy had owned. The image of the run-down 2-storied building may be seen in the famous oil on canvas, Ghentu Residents on Hooghly River that Thomas Daniell had painted in 1788. Courtesy GettyImages.

THE STORY

The National Theatre, Calcutta was ideologically a nation-bound cultural institution designed to promote serious socially relevant Bengali theatricals to the populace with universal access. It was an audacious venture of an unprivileged group of teenage creative minorities residing in the Bagbazar township.

The History of Bengali Theatre begins with the inception of the National Theatre, Calcutta in December 1872 after a lapse of about four years involved in the preparation and presentation of two serious dramas, Sadhabar Ekadasi and Leelabati with a few minor ones, in 1868, and 1872 respectively. While the rehearsing of Leelabati moved from the shelter of Arun Halder to Nagendra’s house, the Bagbazar Amateur Theatrical Society was formed with Nagendranath Banerjee as its Secretary [Mustafi]. The dramas, precursors to the National Theatre, equipped the young Bagbazarians with adequate experiences to use their rare talents in building India’s first public theatre.

A Prelude to Making Bengali Theatre

The fascinating performances of Sadhabar Ekadashi and Leelabati boosted the confidence of Bagbazar Amateur Theatre. The success flamed their desire to display their talent regularly before a wider public. They felt the need for a theatre of their own – a far-fetched object of desire for the penniless theatre-crazy young Turks [Mukherjee]. They decided to sell tickets, as they did last time for Leelavati, not for profit but to meet the development expenses of the theatre building and the stage suited best for public performance. To mean their intention the management printed the phrase ‘For the Benefit of the Stage’ on the admission tickets they released. It was very much in their mind that the democratic stage should have a national image and a name that could differentiate their theatre at once from Calcutta’s English theatres. Accordingly, they renamed Bagbazar Amateur Theatre as the ‘National Theatre’. Girish Ghosh disagreed with the aggressive ideas of his younger associates as he staunchly believed that the group first needed to get hold of an impressive Theatre Building of their own and then fittingly name it ‘National Theatre’. Girish was neither in favour of selling tickets which he always looked down so far. On the contrary, Nagendra, Dharmadas, Radhamadhab, and almost all other important members of the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre thought unanimously that they must go ahead with whatever little they had and grow greater as they moved on. When Girish felt his pieces of advice dishonored, he with a few like-minded fellows finally abandoned Bagbazar Amateur Theatre. A new chapter starts in the history of Bengali theatre at this turning point making a determined move to shift theatre from parlours to public domain in disagreement with Girish. The National Theatrical Society, in short, National Theatre, was born.

Formation

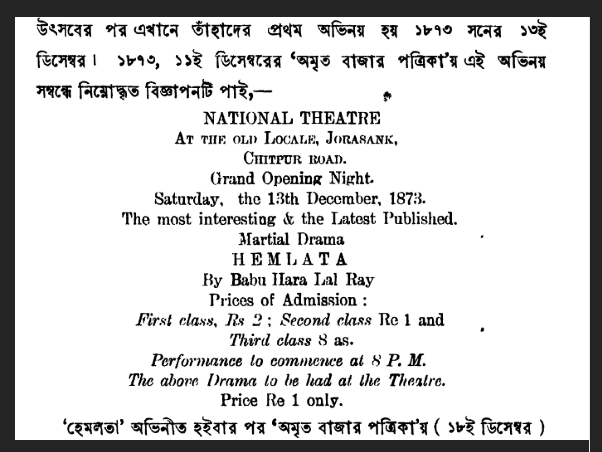

The National Theatre Society had many shortfalls, the most urgent was the lack of a physical working space. Their friend Bhuban Mohan Neogi, a scion of the wealthy aristocratic family of Bagbazar, stepped in to back them. For rehearsing plays, he allotted the large hall on the first floor of the magnificent pleasure house, Bardwari Baithakkhana on the River Ganges, that his ancestor Babu Rashik Neogi had owned. It was then a run-down house, which we may still find in the famous oil on canvas, Ghentu Residents on Hooghly River that Thomas Daniell had painted in 1788 (See above). This riverside pleasure house remained the home of the National Theatre and afterwards of the Great National Theatre. Many respectable men frequented the place to see the progress of rehearsing. Bhuban equipped the rehearsal hall with a harmonium, lamps, and hookahs for the benefit of the performers and the observers, at no cost.

For the inauguration of the National Theatre, the Society picked up a highly controversial play ‘Nildarpan’ by Dinabandhu Mitra unfavourable to the colonial settlers. Nevertheless, support and encouragement came from all sides. Most importantly, the boys found their genuine well-wishers and moral guardians in such eminent public leaders like Sisir Kumar Ghose, Editor of Amrita Bazar Patrika, Nabagopal Mitra, Editor of the National Paper, Mon Mohan Basu, Editor of Madhyastha, and some others. They were pleased to know that the idea behind the effort to start a public theatre was never commercial; nor was it for creating an occupational avenue for the young actors, however urgent their financial need might have been. Amritalal, one of the founders of the public theatre and an actor-playwright of no mean order reminded us that the selling of tickets was started first “to defray our expenses for the theatre and not to fill our pocket“ [Basu. 1933].

Since this Democratic Stage is not dependent on the whims of the affluent class it should empower the middle-class Bengalis to realise their ideology, as the Editor of Amrita Bazar, Sisir Ghosh hoped. “These youngsters supported the progressive thoughts of the Bengali people and after all, they had the grits to make a start with the play Nildarpan. From the core of their hearts, they must have felt the agony of the entire nation suffering silently for so long which found expression today. James Long did go to prison for sympathising with that national outcry that had stirred these young minds [Basu. 1952].

The Stage for the National Theatre

The National Theatre had owned no pavilion but rented a private house to hold their shows. Dharmadas Sur skillfully constructed a theatre stage along the frontage of Madhusudan Sanyal’s sprawling mansion at 365 Upper Chitpore Road. The inauguration took place on Saturday 7 December 1872 with the launching of the play Nildarpan of Dinabandhu Mitra. Babu Benimadhab Mitra was on the Governing Committee as President, and its members were: Nagendranath Banerjee, Dharmadas Sur, Ardhendushekhar Mustafi, Motilal Sur, Radhamadhab Kar, Amritalal Basu, Kshetramohan Gangopadhyay, and a few other middle-class educated teenagers. Girish Ghosh was not associated with the Theatre initially but joined later as its ‘undeclared leader’ for nearly a month.

MADHUSUDAN SANYAL’S HOUSE. The Stage of the National Theatre. 33 Upper Chitpore Road. Presently

owned by Krishna Mullick’s family.

Reactions of Girish

Among so many positive responses from the public and the press, there were two letters, both appearing in the Indian Mirror (19 and 27 December), denouncing the so-called National Theatre on the grounds of lack of proper equipment and poor acting. It was assumed that the writer of the two pseudonymous letters was Girish Chandra Ghose. Girish stuck to his belief ever since that it has been a rash and premature step to make the theatre public without a better house and a better stage. Girish must have felt alienated from the group and being guided by sentimentality he composed a sarcastic rhyme on the performance of Nildarpan hitting recklessly every player personally, who in return instantly admired the witty verse, put a tune to the words and made a hilarious song they voiced loudly in chorus. Amritalal Basu says, “We relished the song“ and Ardhendu says, “All our names were so cleverly put in the song that it reflected much credit on the poetic imagination of Girish Ghosh” [Dasgupta]. This spontaneous act of candid appreciation without a trace of bitterness worked well to help Girish go back soon to the fold of his friends. It exposed the attitudinal differences between Girish and his carefree younger friends that might partially explain the clashes that often took place during the shaping of the Bengali public theatre.

Plays Performed

The National Theatre performed social dramas on contemporary themes, except a historical one, in the three months between 7 December 1872 and 8 March 1873. The names of the dramas played in the National Theatre are:

Nildarpan (7 & 21 December 1872, 1 & 16 February 1973, 8 March 1873); DM

Jamai Barik (14 December 1872, 15 February 1873); DM

Sadhabar Ekadashi (28 December); DM

Nabin Tapaswini (4 January 1873); DM

Leelabati (11 January 1873); DM

Biyepagla Burho (15 January);

Nabin Tapaswini (18 January 1873);

Naba Natak (25 January 1873);

Naiso Rupea (8 February 1873);

Bharat Mata (15 February 1873);

Pantomimes (15 February 1873, 8 March 1873);

Bharat Lakshmi [a dramatic spectacle] (16 February 1873);

Krishnakumari (22 February 1873);

Boorho Shaliker Ghare Ron (8 March 1873)

Jemon Karmo Temni Fal (8 March 1873)

Mostly the plays staged at the National Theatre were authored by Dinabandhu Mitra, a few by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, and the rest by other contemporary writers of importance. Without the prolific pen of Dinabandhu Mitra, the rise of the National Theatre in such a short time seems unimaginable. Dinabandhu’s Nildarpanwas initially performed by the East Bengal Stage in Dhaka in 1861, and it had to wait for 11 years until these empty-handed daredevils launched it at the National Theatre, Calcutta. As we see today, the National Theatre and Dinabandhu were interdependent in their fulfilment. There were also some instances of play written primarily for the benefit of staging at the National Theatre. With a few rare exceptions, all those dramatic works were socially and culturally attuned to the contemporary sociocultural scenario of colonial Bengal, which was one of the good reasons why the National Theatre appealed to the public mind so pervasively.

Besides the serious plays, there were diverse forms of satire, written by Dinabandhu, Michael, and others ridiculing and denouncing the folly or corruption of institutions, people, or social structures. In addition, the National Theatre popularised pantomimes that Ardhendu Shekhar Mustafi composed stylising the English version performed by Dave Carson in the European quarter of the city conveying funny stories in couplets with bodily and facial movements. Pantomimes were branded variously as populist entertainment or as a legitimate theatre. Ardhendu put on the stage quite a few pantomimes that included: Kubjar Kughatan, Naba Vidyalaya, Paristhan, etc. without a prompter which was a common practice since launching Leelavati. Those days, the National Theatre performed new plays every Wednesday and Saturday. To help the performing artists voice their lines correctly, promoters were engaged for the first time in a Bengali theatre [Bandyopadhyay].

In February 1873 the National Theatre was invited to participate in the political and cultural festival of Hindu Mela by representing some nationalistic Bengali dramas in its seventh session. The Mela was led by Nabogopal Mitra, popularly called ‘National Mitra’. He was also one of the patrons of the National Theatre who encouraged them to stage a few nationalistic dramas on the Mela Ground such as Nildarpan [selective scenes] (16 February), Bharat Lakshmi [a dramatic spectacle] (16 February), and also Krishnakumari a play of different genre (22 February).

Girish Coacted at Hindu Mela

As we may have noticed the National Theatre always preferred to stage maiden dramas not yet seen by the public. The tragic drama Krishnakumari was chosen despite being performed at the Shobhabazar Private Theatrical Company on 8 February 1867. The choice was made because the theatre group was fascinated with the engrossing tragedy that Michael Madhusudan had composed for the first time in Bengali prose following Western style. They wanted to stage Krishnakumari even though there was none amongst them to do justice to the character of Bhim Singha except Girish who had parted with the group a few months ago. When approached, Girish generously accepted their invitation on the condition that his name in the advertisements be styled as ‘By an Amateur’ instead of his real name. It was known to everyone in his circle that Girish had had a strong reservation against professional artists who were generally looked down upon in contemporary society. Girish also explained his concern about maintaining the service decorum of his office where he held a respectable position. The term that Girish dictated did embarrass all other performing artists of the National Theatre who claimed to be amateurs too playing for passion and not for money. It was however thought appropriate to advertise the epithet, ‘A Distinguished Amateur’, for Girish Chandra Ghose in the role of Bhim Singha. Girish was, however, not too happy to find the way he was advertised, for some unclear reasons [Dasgupta].

Finally, Krishnakumai Natak was staged publicly at the Hindu Mela where Girish played Bhim Singha spectacularly on behalf of the National Theatre on 22 February 1873. His deep resonant voice and kingly appearance fitted in well with the part he played [Mukherjee]. Mahendra Babu playing the tragic part of Rani Ahalya drew tears from the audience. Michael watched his play on stage and was deeply moved by the genius of Girish Chandra. The National Theatre acknowledged the marvel of Girish playing Bhim Singha in the Krishnakumari natak as a distinguished guest artist.

National Theatre Divided

Shortly after, Girish returned to his old friend circle and joined the National Theatre as an actor and a Director. The reconciliation, however, lasted less than a month. A dispute emerged quite unexpectedly as some discrepancies were found in the ledger. Such an anomaly was unimaginable in a society of dedicated men who declared ’For the Benefit of the Stage’ every night printed on the placards [Amritalal. Puratanprasanga]. They let the entire proceeds of ticket-selling go to the development of the National Theatre, and no one was allowed to take a share of it except Ardhendu Mustafi who needed occasional help [Amritalal Basu. Smriti o Anusmriti]. The differences, though temporarily settled at the intervention of some leading personalities of the time, ultimately led to a division of the National Theatre into two factions. The last performance of the undivided National Theatre was held on 8 March 1873. An advertisement appeared in The Englishman on 8 March announcing the program for “The Last of the Season Saturday 8th March”. The repertoire consisted of 2 satires Burho Shaliker Gharhe Ron by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, and Jemon Karmo Temni Fal by Ramnarayan Tarkaratna followed by 5 pantomimes: Bilatee Babu, Subscription Book, Green Room of a Private Theatre, Modern School, and Mustafi Saheb Ka Pucka Tamasha composed and enacted by Ardhendu Sekhar’ in reply to Mr Dave Carson’s clowning at the Opera House in which he used to sing ‘I Am A Very Good Bengali Baboo’. The program concluded with a Fairy Scene, a Farewell address of Mustafee Saheb, and a parting song composed by Girish rendered by Biharilal Basu.

The National Theatre was split into two theatrical societies after 8 March 1873. The first one adopted the original name ‘National Theatre’ and ran under the care of Girish Chandra Ghose and his followers including Dharmadas Sur, Mahendralal Basu, Tinkori Mukhopadhyay, and others. The second one took a new name ‘Hindu National Theatre’ run under the care of Nagendranath Banerjee, Ardhendushekhar Mustafi, Amritalal Basu, and others. These two competitive societies effectively speeded up the development of modern Bengali theatre through their manifold contributions toward improving upon English-styled theatrical skills and stagecraft and developing socially relevant vernacular dramatic resources, which they did separately and conjointly at times.

The fact remains that the National Theatre was not in a true sense divided into two institutions as generally assumed but two new theatres were established instead. The Hindu National Theatre was founded with defined objectives of a public theatre by a section of ex officio members of the National Theatre. The other one was re-registered with the name ‘National Theatre’ and continued to run without any definite ideology under the leadership of Girish Chandra Ghosh. It was reconstituted and assumed a new identity with the association of Dharmadas Sur, Mahendralal Basu, Motilal Sur, Tinkori Mukhopadhyay, and some others. The Hindu National Theatre was led by Nagendra Nath Banerjee (Hony. Secretary), with the support of Ardhendu Shekhar Mustafi, Amritalal Basu, Amritalal Mukhopadhyay, Kiran Chandra Bandyopadhyay, Kshetramohan Gangopadhyay, and a few other followers.

Reasons for the Split

The National Theatre was closed apparently due to rain as many critics suggested. Others thought that seasonal interruptions could not be the ultimate cause for a permanent breakup of the National Theatre unless there were some preexistent deep-rooted conflicts of interest – either for material gains or ideational differences. There is also a view that the disruption was due to the excessive greed of a few who wanted to be in leadership. [Girish. Naut-churamoni].

After the rift, a dispute arose about the possession of the theatre’s property: its funds, dress, furniture, and other things which could not be amicably settled among parties. As we understand from what Yogendranath Mitra narrated in Puratan Prosonga, the bone of contention for the breaking of the National Theaterwas the disinclination of Girish to promoting the National Theatre as a public theatre until and unless it was equipped appropriately with a good stage and accessories. The other important members, on the other hand, like Nagendra, Ardhendu, Radhamadhab and others fervently wanted to go for having a public theatre in a small way with whatever little means they could arrange at the earliest. Interestingly, it was the same policy matter for which Girish parted with his comrades earlier before the establishment of the National Theatre. The situation reversed abruptly when Girish joined the National Theatre for the first time as the ‘most distinguished artist’ and a man at the helm of affairs. Due to his strong resentment, those in favour of a democratic public theatre were left with no option but to bow out (’আমরা কয়েকজনে ন্যাশনাল থিয়েটার হইতে সরিয়া দাঁড়াইলাম’) and pursue their mission to establish democratic theatre independently. Yogendranath’s comments that the crux of the arguments Girish forwarded rejecting the name of the National Theatre was more than anything but his strong disinclination against the democratisation of theatre because that threatens the high art of theatre so long protected by the elite society. None other than Radhamadhab Kar conceded this view, in whose presence Yogendranath narrated his account [Yogendranath]. Amritalal also found Girish somewhat unfavourable to democratic public theatre [Basu. 1903].

The reasons Girish stated for his disapproval of the naming their theatre the ‘National Theatre’ were:

- The standards of the existing stage, accessories, and scenes were no good for selling tickets to the public in the name of ‘National Theatre’.

- The name was misleading. One might misinterpret the name and think of the theatre as an outcome of a nationwide collective effort of the wealthy people when it was not.

- It should be a shame when people come to know that they were but a few middle-class youngsters, and not the elites, who founded the so-called ‘National Theatre’ provided with poor wardrobes and accessories. [Gangopadhyay]

All these three reasons concern public perception that worried Girish in accepting the National Theatre in the stated conditions. The issues were extrinsic and accidental, and none spoke of the ideological differences that prevented Girish and the young boys from working together. Their differences lay in their policies and principles which were never deliberated fully in scholarly discussions.

Besides his objection to naming the new theatre, Girish had certain personal issues with ‘one or two’ Committee members. Girish sensed that certain guys were scheming to embezzle the ticket-selling money. He did not hesitate to name Ardhendushekhar as one such bad guy [Gangopadhyay]. He accused Ardhendu, a close friend and a powerful contender on the stage, of plundering the theatre’s account on the plea that he was financially disadvantaged and had no occupation other than loitering in the rehearsal hall. The suspicion Girish had in his mind was found baseless [Basu. 1952] and it only reveals how strongly Girish was carried away by his feelings against Ardhendu leading to his decision to leave the party before the coming of the National Theatre into existence [Gangopadhyay].

As Brajendranath Banerjee suggests, it is wrong to accuse someone without sufficient evidence against him. He however could not resist hinting at Girish of his having a ‘knack‘ ’for plotting to secure the stage and its accessories with the help of Dharmadas Sur, after the National Theatre split. Besides, he thought, Girish Babu’s hasty move to register their new society with its old name, ‘National Theatre’ did not go well with his magnanimous image. Girish was originally against naming their theatre the ‘National Theatre’ and even made fun of its objectives, quality of acting, stage, and ambience. It wasn’t until the Theatre made a name and became financially well off that Girish did willfully join the Theatre as a distinguished amateur artist, and a Director as well. His party grabbed the stage and accessories and, as Dharmadas admitted in his biography, the funds, and gently its good name.

Dharmadas put serious blame on the Ardhendu-Nagendra faction that they schemed to declare themselves together with Amritalal and Dharamdas as the Proprietors of the National Theatre Society leaving all other members subordinate to them which he thought immoral and unjust. The allegation was taken up seriously and in a meeting held on 19 January 1873, Babu Nabagopal Mitra, Manmohan Bose, and Hemanta Kumar Ghose were made arbitrators to sort out the differences that arose from a wrong move of Devendra Nath Banerjee to make his brother Nagendra, Amritalal and Dharmadas the proprietors to which Dharmadas objected. It may be noted that Ardhendu’s name was omitted in the minutes. Seven days after, in a special meeting held on 26 March 1873, the Girish-Dharmadas faction resolved that Babu Amritalal be nominated Honorary Secretary replacing Nagendra.

The dispute looked like a desperate attempt by Nagendra and others to retain their hold on the institution they had raised from scratch against so many odds. In a counter-move, the Nagendra-Ardhendu faction not only threw the blame on Girish but postponed the performance of the play Nildarpan at the Town Hall through a notice issued on 29 March 1873, that is the night of the performance:

We are sorry to announce that owing to a breach amongst the members of the above society through the instrumentality of one of the directors Babu Girish Chandra Ghose, the play of Niladarpana, to take place this evening at the Town Hall, is postponed hereby till further notice.

Ardhendu Sekhar Mustafi—Master.

Nagendra Nath Banerjee, _Hony. Secretary.

However, the differences seemed to have been settled in about ten days and Babu Nagendra Nath Banerjee continued to be the Secretary [Dasgupta]. The statements of the contenders reveal that almost all of them considered the breakup a tiff over either financial or leadership issues, except Yogendranath. In the presence of Radhamadhab, Yogendranath reflected it as the old unresolvable conflict between Girish and those who firmly supported the establishment of public theatre on the principles that (1) theatre is an essential cultural force and that (2) art and culture belong to everyone. These stand out as the most historically significant issues in the context of the formation of the National Theatre, the others were only short-lived petty affairs and had little effect on institutional development in the long run. It is a lesson we may take from the fact that the first Public Theatre came into existence because of the commitments of the few have-nots. The episodes of the inner struggles that exposed the human side of theatre history remain beyond the scope of the present study, which is, to delineate the course of the history of modern Bengali theatricals in English style and manner against the reluctant forces of the yatra traditions. We may not, however, justifiably leave out some fundamental questions in differentiating the traditional yatra and a theatre in terms of contents, forms, and styles. Especially because we suspect those were the hidden tender spots responsible for many a setback in coordinating efforts to materialise the dream theatre to play socially related vernacular dramas enacted in modern style on the English stage.

Farewell Night of the Undivided National Theatre

On Saturday 10 May 1873 at Radhakanta Dev’s Natmandir, the Grand Farewell Night of the National Theatre (undivided) played its last performances: Kapalkundala Natak(Dramatized by Girish) ending with Bharat Sangit by the Amateur Concert of Shyambazar under the superintendence of Dharmadas Sur, Stage Manager. [Amrita Bazar Patrika. 8 May 1873]

The memorable night ended by bidding farewell to the audience and reciprocally to each of the two parties, the reconstituted National Theatre and the Hindu National Theatre, before beginning their independent journeys.

Hindu National Theatre

The Hindu National Theatre was the first splintered theatre established by the Nagendranath faction. The Theatre was inaugurated with the play Sarmistha in public on 5 April 1873 at the Grand Opera House on Lindsay Street – a pride of the British and European elitists of Calcutta, about two weeks before the new National Theatre performed Nildarpan on 19 April 1873 at Shovabazar Natmandir. It was indeed baffling how an unheard-of humble native company had been allowed to stage dramas, that too in a native language, on the iconic British stage. However, the inside story of the contemporary British stages in Calcutta reveals that the negotiation with Bengali theatrical enterprises was then looked upon as a boon for the English playhouses. The Opera House had been desperately in need of money for its revival, so much so, that its British management was ready to demean their prestige and forget their racial bias for a while.

It was time when Alessandro Massa took over the office of Impresario in Calcutta. Soon he realised his inadequacy in meeting the demands of the local aficionados for quality Italian opera artists and attractive repertoires. He did his best to present good Italian operas, promote an opera culture in Calcutta, and generate income to sustain the operatic infrastructural facilities in the town. Massa had a small working committee to liaise with the public and facilitate administration. We are however unsure if Massa, or his committee, was responsible for inviting the Hindu National Theatre to stage their Bengali dramatic performances at the Grand Opera House during April 1873 for three nights.

The young men of the Hindu National Theatre with indomitable spirits grabbed the opportunity to stage their modern plays of sociocultural significance, portraying life in Colonial Bengal before an audience consisting of Anglo-Europeans and some opulent Indian theatre lovers as well. At Opera House, Lindsay Street the Hindu National Theatre performed the following three dramas in April 1873:

Sarmistha (Michael Madhusudan Dutt), 5 April 1873

Bidhaba Bibaha (Umesh Mitra), 12 April. 1973

Kinchit Jalajog ((Jyotirindranath Tagore), 19 April 1873

Ekei Ki Bole Sabhyata (Michel Madhusudan Dutt) 19 April 1873

Pantomimes (Ardhendu Mustafi’s plays):

Model School and its examination. 2* Belati Babu. 3. Distribution of

Title of Honour. 4. “Mustafi Sahebka Pucca Tamasa”

Seven days after the Opera House contract had ended, the Hindu National Theatre performed at the Howrah Railway Theatre their best-loved play, Nildarpan on 26 April 1873. The performance

however was resentfully criticised by one Dinanath Dhar in Amrita Bazar Patrika on 12 June 1873: “Mr. Wood out-did his part, so was not ably rendered. He ought to read the passages in Hamlet, sc. ii, Act III.” The criticism was unwarranted, and disheartening for the party, especially because they guessed Girish might have been the man behind the name ‘Dinanath Dhar’. “But unable to do much in the face of competition with Girish Chandra, they left for Dacca by the 1st week of May” [Dasgupta]. Before setting off, they changed their address to Kaliprasanna Sinha’s house at Jorasanko. the Hindu National Theatre toured around the districts for a month playing theatres. At Dacca, Hindu National played Nildarpan, Ramabhisek, Naba Natak, Sadhabar Ekadasi, Nabin Tapasvini, Jamai Barik, and Krishnakumari with overwhelming success. The team returned to Calcutta with rejuvenated energy and hope. Probably it was the time when the members actively considered shaping the Hindu National Theatre into a regular public theatre settled with the necessary infrastructure, however small it might be, to fulfil their most cherished desire, in other words, it was then the nascent idea of forming the Great National Theatre sprouted in their mind.

The National Theatre (Girish Brand)

The reconstituted National Theatre under the governance of Girish presented several plays at Raja Radhakanta Deb’s Natmandir:

Nildarpan 19 April 1873.

Kinchit Jalojog (Jyotirindranath Tagore), 26 April 1873.

Ekei Ki Bole Sabhyata, (Michael Madhusudan)

Dispensary, Charitable dispensary and

Kapalkundala (Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novel dramatized)

Encouraged by the successful tour of the Hindu National Theatre, the new National Theatre followed suit soon and travelled in September to Dacca, Murshidabad, and Varanasi with Moti Sur, Mahendra Bose, Gopal Das, and others under the management of Rajendra Pal and Dharmadas Sur in the absence of Girish whose leave was supposedly denied by his employer. On reaching Dacca, the new National Theatre haughtily advertised: “The Real National has now arrived’, and staged several plays in the compound of Jivan Babu (Jivan Krishna Dev?). The National Theatre could not attract much applause from the local gentry. Their late entry might be one of the reasons for the poor response from the audience already won over by the performance of the Hindu Theatre.

Both the Hindu National Theatre and the new National Theatre suffered losses irrespective of the fact that the Hindu National had won the hearts of the Dacca theatregoers. The new National Theatre suffered much more and ultimately had to leave for Calcutta by mortgaging the scenes with the Hindu National Theatre. Nevertheless, the toiling of both the theatre groups was not wasted. The plan of itinerant theatricals was expected to ‘create a taste for the drama in the Mufassil’ as the Hindoo Patriot viewed on 8 September 1873. [Bandyopadhyay] They also toured places like Rajshahi, Boalia, Rampur, Chinsura, and Berhampore to promote theatre. It was Ardhendushekhar Mustafi who took the initiative to wander with Bengali theatrical troops in Bengal townships and later to the North Indian cities for the promotion of Bengal theatricals and that is why he was called ‘The Missionary of the Bengali Stage’.

Combined Performances

Back from Dacca, the Hindu National Theatre performed twice in collaboration with their opponent, the new National Theatre. The first performance, Krishnakumari, was a benefit show for the orphans of the late poet Michel Madhusudan Dutt held on 6 July 1873 at the Opera House under the banner of the National Theatre where Ardhendu Sekhar Mustafi and a few others of the Hindu National Theatre took part. That was the first instance of the party going outside on contract. The second performance was held on 16 July 1873 to celebrate the Annaprasan ceremony of the little Prince Pramadanath Ray at Dighapatiya Rajbati. Girish, Dharmadas, Amritalal, and Nagendranath did not participate in these events. We may notice that these combined performances were held not as instances of camaraderie but as special occasions to meet certain social purposes that appealed to some genial warm-hearted members to join hands forgetting rivalry.

Anniversary of the National Theatre (Undivided)

On 7 December 1873, the new National Theatre and the Hindu National Theatre observed the first anniversary of the Original National Theatre at Sanyal House, its original site in Chitpore. The Englishman of 10 December 1873 wrote :

“On Sunday, the 7th instant the first anniversary of both the Hindu theatres (sic) was held with much éclat and enthusiasm. The Vene’ble Raja Kali Krishna Deva Bahadur, K.G.S. presided.” The dramatist Mon Mohan Basu, who spoke on the occasion, while eulogising the young men who had brought a public theatre to the citizens of Calcutta regretted the parting of ways on the part of friends, but found comfort in the fact that hereafter the city would have two theatres instead of one.

Though the original National Theatre was publicly commemorated on 7 December 1873 it was very much alive after that in the spirit of its progeny, the Hindu National Theatre, the Great National Theatre, and the Great National Opera by carrying out its mission of making democratic theatre ’in a national way’. Girish on the other hand never declared any mission goal of the brand of his National Theatre he proliferated nor did he attempt to justify the repeated use of the borrowed name he discarded earlier as inappropriate.

Passage To The Girish Epoch

That was the dawn of the Bengali stage when a group of young talents of Bagbazar on the outskirts of the ‘Town Calcutta’ marked their innovative presence. “Like the knights of fairytales, Girish Chandra, Amritalal, Ardhendushekhar, Dharmadas Sur, Motilal Sur, Bel-Babu, and Kshetra-Babu filled the Bengali mind with awes” [Chowdhury, D]. The time is marked as the premier epoch of Bengali democratic public theatre that ended with transforming the Great National Theatre into a Girish-brand National Theatre in 1877. From the last of the Great National Theatre to the commencement of the Star Theatre can be conveniently labelled ‘Passage to the Girish Epoch’. The Epoch ushered from launching the Star Theatre as a hardcore commercial enterprise run by professionals headed by Girish. This section discusses the passage leading to the Epoch of Girish Chandra, the Epoch itself lying beyond the scope of this essay.

Five different institutions were connected historically to the revolutionary idea of theatrical democratisation. Those were: – 1. Bagbazar Amateur Theatrical Society: a small society of local theatre-crazy teenage boys, 2. National Theatrical Society: Originator of the first public theatre. An initiative of the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre Society 3. Hindu National Theatre Society: A splinter theatre of Nagendra-Ardhendu faction 4. Great National Theatre Society: An initiative of the Nagendra-Ardhendu faction 5. Great National Opera Society: A Nagendra initiative.

Because of its policy differences, the reconstituted National Theatre was appropriately considered a new brand of National Theatre established by the Girish faction, standing apart from the mainstream of the National Theatre initiated with democratic principles. The Girish brand of the National Theatre with its distinctive traditional characteristics was proliferated twice more, completing the transformation of the amateurish idealistic theatrical culture into a profit-making commercial enterprise starting at the last leg of the Girish brand of the National Theatre operated under Pratap Jawhuri.

Girish had been directly or indirectly related to most of the above institutions. He acquired some but none of them he built from scratch. Girish was the undeclared leader of the boys of the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre, primarily concerned with their product and performance. Being a cautious leader, he was not always ready to go with the adventurous idea of making a national theatre that the penniless boys had proposed. Moreover, having been a full-time employee of Atkinson’s firm he had no free time for involving more in theatre. Girish stood firmly against any idea of setting up a public theatre and said, Our stage, scene, and theatrical dresses are not good enough to justify selling tickets in the name of National Theatre. He thought its high-sounding name would baffle the public and mislead them to take the humble theatre raised by a crazy lot of middle-class down-and-out teenagers for a National Theatre of India that was supposed to be founded by the up-scale citizens’ collective efforts [Gangopadhyay].

The notion of ‘national theatre’ the boys had in their minds stood poles apart from the kind Girish had ever imagined. They envisaged their national theatre as a democratic stage for performing serious socially relevant drama to people without any discrimination. The boys struggled devilishly to make it happen, almost out of nothing, since they had nothing materially – no stage materials, furniture, dresses, scenes or screens, nor a hall of theatre. In their endeavour to free Bengali theatre from the privacy of the palace theatres, among other good things, they had the moral support of the public and the press, besides their zealousness. The press was overwhelmed with eager expectations and was ready to serve as a watchdog to monitor their progress. Several native newspapers, particularly Amrita Bazar, Madhyastha, Sulabh Samachar, and National Paper mindfully reported and reviewed performances of the Theatre with their recommendations. While reviewing the play Nabin Tapaswini of Dinabandhu Mitra on 4 Jan. 1873, the Amrita Bazar spoke straight from the heart their feelings and anxiety about the enormous responsibility of the National Theatre carrying the qualifier ‘national’ within its name. They argued:

When the qualifier ‘national’ is admitted into the theatre’s name, it is only expected that utmost effort be made to honour its purport. To do that, the play themes needed to be decided upon before the dramas were written so that they might inspire the audience with a spirit of righteousness, besides entertaining them. Being conscious of the higher purpose of the theatre, both the performers and the audiences were to gain an elevated state of mind, to hate sins and adore piety, ridicule the rotten social customs and conducts, and see that good social practices and ideas stay unharmed. The theatre excites patriotic feelings in the audience by reminding the glorious events of the past and showing examples taken from the lives of local heroes. All these may not happen overnight but the limits of the possibilities ought to be explored with the utmost sincerity. In short, that day, Sisir Ghosh of Amrita Bazar cleared many wrong notions about the attribute ‘national’ by interpreting it as a standard of nationalistic values and not in the sense of a model institution for national representation, as Girish imagined.

For designating the first-ever Bengali public theatre, the name ‘National Theatre’ was chosen through a long deliberation by the enlightened theatre enthusiasts of Calcutta. Yet it remains a debated name in history. Girish Ghosh was the most critical about tagging their humble theatre inappropriately with such a high-sounding name. He dissented from the majority decision and left the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre Society. The ardent teenage members of the theatre society of the Bagbazar never stopped before inaugurating the National Theatre on 7 December 1872 to mark the beginning of the Bengali public theatre. The Theatre was defunct soon after the last show of the undivided National Theatre held on 10 May 1873. Interestingly, Girish who strongly opposed the naming of the ‘national theatre’, for some superficial reasons, felt the name worthy of being used in designating three proliferating theatres of the Girish brand of National Theatre he ran after the disassemble of the original National Theatre (7 Dec. 1872 – 29 March 1873), established by Nagendranath Banerjee and others.

As the above advertisement shows, while announcing the debut performance of the new National Theatre established by the Girish faction they nowhere disclosed that their Theatre was a new and completely different theatre than the one with the same name recently dislodged. The newspaper ad with its make-believe appearance of an insertion of the ‘original’ National Theatre might have been intended to hoodwink the public evading moral obligations and decency. This may remind us how the faction made a false announcement at Lucknow claiming they were the ‘original National Theatre’. The following were the three proliferated theatres that Girish christened ‘National Theatre’:

1. National Theatre. 13 December 1873 – 29 March 1877

Established by Girish Faction.

2. National Theatre.15 September 1877 – 1 Jan 1881

Lessie: Girish Ghose. A renamed Great National Theatre

3. National Theatre 1 Jan 1881 – 5 Feb 1883

A commercial establishment, Established by Pratap Jawhuri

On 5 February 1883, the sequel of Girish Brand National Theatre ended. Girish, along with Amritalal Mitra, Binodini, and a few others, left the last avatar of the National Theatre to start the Star Theatre.

Star Theatre opened on 21 July 1883 with Girish Chandra’s mythological drama Daksha Yagna. When we are clueless as to why Girish repeatedly used the name he damned initially, there has been no lack of evidence of the trouble it created for scholars and researchers to study the history of the emerging Bengali theatre. After Girish, Kedar Chaudhuri became the manager of the National Theatre. Finally, after the show of Bou Thakuranir Hat of Rabindranath Tagore was staged, on 3 July 1886, it was sold in an auction late in 1886. The purchaser was the Star Company which demolished the National Theatre building at 6 Beadon St. It was on this site that Minerva Theatre came up. The Minerva Theatre still stands in its new building, the original being destroyed in a fire in October 1922.

Observations & Interpretations

Though he never said it in many words, Girish was baffled by the unbelievable success of the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre in launching the National Theatre belying whatever he had said in his cautionary advice. Girish took the following lessons from the debacle:

- Theatre potentially is a profitable enterprise

- The theatre sells tickets if the drama is good

- The name ‘National Theatre’ is good

- The name earns intangible assets of Brand Goodwill

The changed perspective of Girish, toward theatrical enterprise, was noticed by some writers. Ahindra Choudhry suggested that Girish Chandra eventually realised that theatre was an instrument of social education, and felt the need for a professional theatre to benefit the Bengali society at large. He also started believing that professional theatre had the potential to be a profit-making enterprise. The possibilities encouraged Girish to buy the license from Bhuban Neogy, to run the Great National Theatre, in his brother’s name. Bhuban was then in a state of despair because of being continuously harassed by unscrupulous speculators. Last time it was Krishnadhan Mukherjee who left without paying him the theatre’s rent. Bhuban Neogy happily leased the Great National Theatre to Girish. Girish renamed the Theatre the ‘National Theatre‘ [Ahindra]. It was the first time Girish had an opportunity to steer a public theatre as its master. In performing Sadhabar Ekadashi, Leelabati and Krishnakumari Natak, Girish proved by this time his extraordinary talent for growing into a great actor and a stage director, he was yet to be tested for a theatre entrepreneur. Not before long Girish confronted a serious allegation of administerial negligence from his brother Atulkrishna Ghosh, a young practitioner of the High Court. Girish did not have the slightest idea, it seems, of the precarious financial state of his theatre that was created because of his over-dependence on a few questionable characters. Bhuban Babu had suffered a great loss on account of their unchecked misdeeds. It was all because Girish preferred to remain happily absorbed with his office work during the day, and with his writing, rehearsing, and acting the rest of the time. The worried Atulkrishna was determined to stop all malpractices and save Bhuban Babu from further loss and damage. He proposed Girish, his ‘Mezda’, “Exit the lease agreement, or let us be parted” [Gangopadhyay. ”হয় তুমি থিয়েটাব ছাড়ো, নচেৎ এসো আমরা পৃথক হই।“]. Girish never challenged the charges Atulkrishna accused him of, and snapped the lease contract heeding his advice. We understand from Abinashchandra, his biographer, that henceforth Girish was pleased to make any man of his choice the proprietor of the Theatre under whom he worked as a salaried Director-in-chief, and never attempted to take overall charge of a theatre until the Star Theatre was set up.

In 1879 Gopichand Sethi, a Marwari gentleman, arrived at the theatrical scene as the sub-lessee of the National Theatre for a short time. After Gopinath, Kalidas Mitra held the Theatre on rentals for a couple of months followed by new adventurers trying their luck for a month or a week. The condition of the National Theatre worsened as never before. Lastly, Yogen Mitra, nicknamed ‘Lanka’ Mitra, hired the Theatre to start alluring a huge audience by offering small gifts, like rings, earrings, soaps, and perfumes. The making of gifts for promoting theatre was in all probability introduced for the very first time. Very soon the list of gifts expanded to include fresh fruits and vegetables before finally declaring insolvency of Bhuban Niyogi’s property. The house of the Theatre was put on auction. Pratap Chand, the shrewd Marwari Businessman bought out Calcutta’s first Public theatre at Rs. 25,000. It was built by a proud team of full-time amateur artists and Pratap Chand converted it into a hard-core commercial public theatre run under a whole-time professional Stage Director in person of Girish Chandra Ghosh. At the commercial public theatre, still under the banner of ‘National Theatre’, the first play, Hamir, was enacted on 1 December 1881.

After Girish, Kedar Chaudhuri became the manager of the National Theatre. Finally, after the show of Bou Thakuranir Hat of Rabindranath Tagore was staged, on 3 July 1886, it was sold in an auction late in 1886. The purchaser was the Star Company which demolished the National Theatre building at 6 Beadon St. and the Minerva Theatre was built on that ground.

Girish quietly withdrew his reservations against the name. He never attempted to explain why he adopted the name ‘National Theatre’ which he had shunted before. He took the name without adding any qualifier to differentiate his brand from the original one, making it extremely difficult to access elements of the history of the origin and development of Bengali theatre with any degree of certainty. The uncertainty grows with time, as collective memories of the people fade, and the historical records get corrupted and lost.

The new Girish brand of Theatre was inclined to follow the traditional values of the yatras which were safeguarded so far by the elite society against vulgarity and perversions allegedly afflicted by the commoners, including the underprivileged class and casts (হাঁড়ি, শুঁড়ি), as Girish suggested in his notorious lyrics ridiculing the Nildarpan players [Girish].

The Original and The Girish Brand National Theatres

The first public theatre, the original National Theatre, was alive for nearly four months(7 Dec. 1872 – 29 March 1873). After its closure, Girish branded his sprinted theatre in the borrowed name of ‘National Theatre’. Girish proliferated his brand of National Theatre twice covering a full decade. That means, Calcutta always had a theatre named ‘National Theatre’ between 7 December 1872 and 5 February 1883. Significantly, the first phase marked by the birth of the public theatre, or the original National Theatre, lasted only for four months – an insignificant proportion of the total timespan of 124 months:

- The original National Theatre – 7 December 1872 – 29 March 1873 4 months

- Girish brand National Theatre – 29 March 1873 to 5 February 1883 120 months

Whatever happened during these 124 months, that had a mention of ‘National Theatre’, was presumed by default a concern of the ‘Girish Branded National Theatre’, as it was statistically far more probable than the short-lived original National Theatre. Moreover, ordinary people are rarely accustomed to verifying the relevancy of facts by dates, instead, they look for some names, stories, and anecdotes for a cross-check. Such was the kind of practice followed even by some well-known historians who often hastily claim Girish to be the ‘Father of the Bengali Public Theatre’ giving exposure to their overwhelming love and hero-worshipping at the same time their disloyalty to history. First, they did so by wrongly equating the ‘procreator’ (জন্মদাতা) with the fostering father (অন্নদাতা). A father may denote someone who originates a life or a thing that never existed beforehand. As discussed earlier, Girish made it public that he had no connection with the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre Society when they conceived and founded the National Theatre [Gangopadhyay]. It was chronologically wrong to suggest Girish as the ‘Father of the Bengali Public Theatre. Anachronism and garbling of facts were the unfortunate outcomes of the speculative move that Girish had taken to buy the goodwill free by adopting the old name ‘National Theatre’ for his new theatres. In many ways, posterity had to pay the cost of the chaos that Girish had created, the worst among them was the suffering from collective cultural dementia.

Messed-Up History of the National Theatre

The bewildering newspeaks made people forgetful of their heroes without whom the democratic Bengali theatre would have never happened, the awesome repository of Bengali dramas never grown, nor the modern audience ever born. Once people boasted about all those path-makers of the renaissant Calcutta as unforgettable immortals until they were found lost in oblivion.

Ahindra Chowdhury, in Girish Lecture 1957 sponsored by Calcutta University, unhesitantly admitted that the series of Girish lectures, some of which were deliberated by theatre historians, impressed on the public minds as more an appreciative recounting in praise of Girish Chandra, ‘the creator of the National Theatre’, than any critical appraisal. He also warned his audience that he was to deliver his lecture likewise, dedicating his respect and gratitude to the immortal soul of Girish Chandra [Chowdhury. 1958]. As we notice, to Ahindra Chowdhury, like many other writers, Girish was taken for granted as an unquestionable ‘Creator of the National Theatre’. Investigations into the history of the Bengali public theatre are gagged with disproportionately biased information, manipulated narratives or facts, more than scarcity of information or information poverty, the theatre history research now faces [Rakshit].

The following extracts from the writings of some well-known theatre personalities and historians of repute may adequately reveal the extent of distortion of facts irreversibly imprinted on the social mind:

One of the veteran theatre personalities, Aporesh Mukhopadhyay, claims that “Girish Chandra established a theatre for the first time in this country.” Then he says, “That means Girish fed the theatre with staples for its survival and that is why he was called the ‘Father of the Native Stage’.” We may note that Aporesh furnishes no essential references to the things related to the origin of the theatre, such as the name of Bagbazar Amateur Theatre or its pioneer members to indicate if he talks of the original National Theatre or of the theatre that Girish established and registered with the old name. It must be the Girish-brand National Theatre that Aporesh talked about because the original National Theatre was established without Girish who left beforehand. Aporesh also comments that “There was no one like senior or junior uncles (‘খুড় কি জ্যাঠা’) around to look after the theatre but Girish Chandra alone was there for it, and only he can legitimately claim the fatherhood of the Bengali stage.“ [Mukhopadhyay, A] The situation Aporesh describes was only relevant to the Girish-brand National Theatre that Girish reared up all alone. On the contrary, the original National Theatre was not founded single-handedly but collectively by a group. Fortunately, the names of the founding group members were recorded by Amritalal Basu who joined them subsequently:

“Every time I look back and think of the establishment of the public theatre here in this country, four personalities loom at large without whom it could never have possibly come into existence. Among those four were (1) Nagendranath Bandyopadhyay – an ingenious organiser per se and a distinguished actor. (2) Dharmadas Sur – an aide to the organiser Nagendra, an excellent craftsman. (3) Ardhendushekhar Mustafi – An actor moulded by God’s hand and an unparallel theatre teacher the kind of master who never said, ‘you are no good’ to any of his students, and was able to make a memorable picture out of a two-worded dialogue. (4) Bhuban Mohan Neogi – It was he who provided the theatre team with a working space and later funded a decent Theatre building on Beadon Street.” [Amritalal. 1952]

Dr. Hemendranath Dasgupta, the Girish lecturer at Calcutta University, holds quite a different view, and states with conviction, “In short, Girish Chandra Ghose was really the Father of the Bengali Stage.“ In support of his convictions, he offers no justification but further opinions such as:

1. “Indeed, Girish Chandra was the master spirit from whom all inspiration came.” He says this without explaining what the ’master spirit’ is, and what could have been the real reason for his leaving the Society before it was renamed National Theatre, other than his objections to the naming which is found rather flimsy because he adopted the name ‘National Theatre’ for all the theatres he founded later on by himself.

2.“the National theatre was like a son to Girish Chandra, whom he begot, nursed, gave him training but was absent before the formal Namakaran ceremony was performed.” Hemendranath never explains why he prefers to call it an ‘absence’ meaning of his non-appearance instead of his ‘quit’ from the Bagbazar Amateur Society which Girish surely did not do without a definite cause.

3. Without an attempt to clarify his statement historically, Hemendranath maintains that Girish ‘founded the National Stage again[my emphasis]’, implying Girish also had founded the first National Theatre. [Dasgupta.v2]. Hemendranath speaks of Girish, in detail, in his books, History of Indian Stage and Girish Pratibha. He highlights his huge contributions to the Bengali stage, with his masterly acting, prolific playwriting, and entrepreneurship. Hemendranath firmly believes that “even without considering those [contributions], we may assuredly call Girish Chandra Ghose as ’the Father of the Bengali Stage’ from the time of Sadhavar Ekadasi.” Girish was by any standard a superstar, ‘A sun amongst stars’ as Ahindra Chowdhury found him. However, it was not a reasonable idea to call someone ‘The Father of the Bengali Stage’ just because he played Nimchand magnificently in Sadhabar Ekadasi. The sobriquet ‘Father of the Bengali stage’ may be used to call someone without whom the Bengali stage was never born. Bagbazar Amateur Theatrical Society was an institution to claim that right.

4. Ahindra Chowdhury, one of the most respected theatre personalities of the 20th century, thinks of Girish and his genius of acting during those early days when he had not started composing drama and was famed only as a great actor. Girish started composing dramas much later to feed the Girish-branded National Theatre, and subsequently the Star Theatre. Ahindra writes: “Shining in the footlight of Star Theatre, the Bengali drama was enthroned once again.” A new epoch of Bengali Theatre dawned. We presume Ahindra meant Girish was the Father of the Bengali Stage ‘shining in the footlight of Star Theatre’, and not anytime before that. [Chowdhury.1959]

5. Girish was unanimously acknowledged as the most compelling leader of the Bengali Stage caring to do things mindfully and correctly for the development and sustenance of the Bengali theatre. Despite many serious differences with Girish, their ‘undeclared leader’, the young Turks of Bagbazar respected him as more knowledgeable, intelligent and senior to them. Ardhendu, in his lecture at Minerva, declared that “Girish Chandra gave a new life to Bengali stage. Let the historians decide whether he was the father of the [Bengali] theatre. But it remains true that Girish Chandra took due care of the Bengali theatre [Mustafi. 1900]. When Ardhendu, one of the unfailing admirers of Girish, spoke of his commitment to the well-being of Bengali theatre, we were perplexed about finding a probable period when Girish might have played a champion defender of the theatre. For Girish, the period of his leasehold should have been the best time to invigorate Bhuban Neogi’s theatre, the period was however lamentably turned into one of the worst phases in the history of the Bengali theatre due to administrative inactions. As we know, the situation was temporarily saved by Girish’s exiting the lease contract at the insistence of his brother Atulkrishna. Before the august presence of Girish, the National Theatre died after suffering momentarily from the humiliation of offering fruits and vegetables as promotional gifts to the theatre audience. The Theatre went to auction and was sold to a Marwari businessman. The icon of the Bengali public stage – the pavilion of the original National Theatre was hammered down. Girish had witnessed these assaults on the historic achievement as an onlooker and not a defender, as expected.

6. Ahindra Chowdhury’s references to the Girish Epoch corroborate with the recorded history. Under the leadership of Girish, awakened a new epoch of Bengali theatre. The epoch, known as the Girish Epoch, started with the inauguration of the Star Theatre on 21 July 1883, leaving behind the Premier Epoch initiated by the Bagbazarian Amateur Theatre completely out of focus. The National Theatre, the first democratic public theatre in the country they had founded, lost its identity soon after the Girish-brand National Theatre was launched in December1873.

Endnotes

Why This Essay?

The essay warrants the need to rewrite the history of the origin and development of public theatre in Bengal, judiciously weeding unsubstantiated matters of sentimental and partial bearings. This helps in inquiring into the formation of the National Theatre and finding the extent of its contribution to the flowering of the Bengal Renaissance.

The focal point of our studies is the democratic public theatre and the social cultural and political dynamics involved in shaping the National Theatre to inquire into the possible relationship with the Bengal Renaissance. The word ‘national’ in the name of the ‘National Theatre’ was interpreted as ‘Theatre for one and all nationwide’. The rise of a culture of personal rights replacing a culture of community all over the country is one of the democratic wills that contextualised the term ‘national’ to the National Theatre.

Democratic Theatre

The demand for universal access to theatre by setting up a democratic public theatre was voiced as early as the mid-nineteenth century. While reviewing the play Vikramurvasi natak on 24 November 1857 the Hindu Patriot expressed the public will for building a public theatre to benefit the common people un-admissible to the palace theatres. A little over two years later, on 11 February 1860, the Hindu Patriot advertised a prospectus of a Calcutta Public Theatre designed by Radhamadhab Haldar and Jogendranath Mitra of Aheeritola. The project, however, never came to the stage. A decade later, the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre group came up with the same agenda as the unborn Calcutta Public Theatre had formulated, emphasising the democratic principle of the public theatre, promising access to everyone indiscriminately nationwide. The Society was set up curiously by a few local teenagers bubbling over an irresistible passion for dramatics. They were ardent to do theatre rather than prevalent yatra, in a modern way as the English theatres did in Calcutta, particularly at Lyceum.

Interactive Theatre

Historically, in some forms of yatras, the actors had the scope of interactions with the audience seated around the play area with no wall in between. Notwithstanding the physical constraints of an English proscenium stage, the actors of the National Theatre found ways to participate with the audience and the dramatists to ensure quality performance. They could break the Fourth Wall – the wall that traditionally separates the performer from the audience. We find evidence in history and press reviews that the dialogues between the actors and the spectators started at the rehearsing stage when many theatre critics and enthusiasts frequented their place to take a look and make comments which were received and responded to in words and actions.

The Bagbazar Amateur Theatre had a friendly working environment, which allowed close interactions with the audience and the authors. For instance, the management opened a special category of Class 4 membership on the thoughtful suggestion of a well-wisher, Upendramohan Thakur. The management was always open to any suggestion made by the audience and was unhesitant to seek consultations with knowledgeable audiences in any matter, whenever necessary. We may recall how Dinabandhu Mitra, the author of Sadhabar Ekadasi, jumped to cheer at the impromptu act of Ardhendu in kicking Atal – a scene out of the book. Dinabandhu admitted that it was an improvement to the author and the change must go into the next edition. There were also instances of seeking consultations proactively. Amritalal, then the Stage Manager, had faced a dilemma in casting a ‘kissing’ scene from the play Noyesho Rupaiya. Since the author was not present to advise him, Amritalal approached Sir William Hunter, a regular visitor to the Theatre and accepted his pragmatic advice against showing the scene publicly as he felt the society was not yet ready for it. Such public participation and socialisation, boosted a feeling of togetherness, the bedrock for meaningful participatory developmental activities.

Radical Theatre Opposing Yatra

Democratic characteristics apart, the National Theatre was envisaged as a radical institution. It was born with a desire to break with the continuity of social institutions in the context of theatricals. The Bagbazarian boys’ response to the call ‘Let’s do theatre’ of their leader Nagendra was a positive step to shun away from the legacy of the yatra that raged since the early 19th century in increasingly impolite forms. The public was jubilant with the musical yatras including the lowly “Nabo Yatra’ with a few exceptions of classical yatra performances hosted privately at Calcutta palace houses. Rajendralala Mitra observes that yatra-palas of low taste and vulgarity were not favoured by the patrons of the new cultural wave, they were rather fond of the theatre [Mitra] The classical form of yatra however was still being performed alluring many erudite minds of refined taste, including some stars and superstars of the Bengali stage. Girish Ghosh and Radha Madhab Kar had an affinity and a deep appreciation for the art of yatra abhinaya. Girish, as we understand, in 1867 took the initiative in making an amateur yatra group to play the Sarmishtha yatra of Michael Madhusudan Dutta. Girish was also involved with an amateur yatra party that launched the Usha-Haran pala of Manilal Sarkar, at the time when the National Theatre was inaugurated. [Dasgupta. Girish] Between the scenes of this play, Radha Madhab Kar sang the famous satirical song ‘Lupotobeni bohiche tero dhar’that Girish composed to ridicule the Nildarpan actors. [Dasgupta. Girish Pratibha] The lyric itself, particularly its last line, betrays the satirist’s lack of sensitivity to the rightful demands of the commoners to enjoy theatre.

Alluring Yatra Abhinaya

The leading members of Bengali intelligentsia and theatrical artists were not equally convinced of the comparative cultural benefits of a modern theatre over the traditional yatra. The soul of a yatra is musical and of a theatre visual. That is why Amritalal explains that a Yatra with its songs and musicals is to be heard, and theatre with its acting and visual effects to be seen. As he says, his group wanted, from the beginning, to minimise the songs and musicals to enhance focus on the movements and actions on the stage. In contrast, Girish with his inclination toward Yatra forms and styles, thought it prudent to incorporate some typical features of the Yatrainto the dramatic representation of Sadhabar Ekadasito attract general spectators attuned to Yatra culture. Girish did it by defying the maxims of Dinabandhu who abided by the modernistic Western norms. None of Dinabandhu’s works featured any unnecessary prastabana, sutradhar, naut, nauti,or musical interlude. [Dasgupta. 1928]

Natyo-Abhinoy /Sahityik Abhinoy

One of the most eminent erudite critics of modern times, Dhurjatiprasad Mukherjee, observed that two schools of play-acting were in vogue during the days of Ardhendu-Girish. The first one was recitation-centric vocal expressions which he defined as Sahityik Abhinoy. The other was primarily a visual expression of facial and body language manifested through rhythm, motion, and pause. Dhurjatiprasad appreciated Girish’s grave thunderous voice and stylish pronunciation that suited well to reading Gourish blank verse. The acting of Ardhendu Shekhar, on the other hand, as he observed, had little scope for recitation but reflections of a series of images that played in spectators’ minds. Dhurjatiprasad thought it was possible because of his incredible control over every body movement in translating the microscopic changes in feelings and emotions. This was why Dhurjati Prasad perceived Ardhendu Shekhar as a perfect actor and his acting was dance-centric. [Mukhopadhyay, DP]

We discussed the tight-lipped Yatra fans at some length in the essay posted last time. A large proportion of the spectator liked to hide their preferences for the glamorous and rhetorical appeals of a Yatra that a modern theatre rarely could deliver. Dinabandhu knew that the public taste for art appreciation was still clinging to traditional values and the onus was on him as a dramatist to uplift their theatre sense. Girish on the other hand failed to find anything wrong in adding some fun features to warm up the audience. His profound knowledge of Yatra and Theatre and his understanding of their sociological dimensions were of no help. It might be because of his upbringing in an environment of Yatra culture and himself a magnificently built Yatra artiste Girish turned into a Yatra addict.

His clear and resounding voice and majestic demeanour in the protagonist role he played in mythical and historical plays made Girish an unsurpassable legendary actor of all time. His way of acting might not be suited well for realistic social dramas, yet a few memorable enactments of social roles he had to his credit, particularly in Sadhabar Ekadasi and Leelavati nataks. Amritalal Basu found Girish playing Neemchand in Sadhabar Ekadasi so magnificently that he could not help calling him Naut Guru of Bengal – the Maestro of the Bengali Stage.

Theatre its Modernity

Amritalal adored Girish as an unparalleled superstar of Bengali theatre. But he was somewhat unsure about some of Girish’s modes and manners of delivery. Amritalal had realised by observing the players performing on Lewis’ stage that “the thunderous human voice is not so good to hear, and affection and mannerism are no acting”. [Basu. 1952] In saying so he might have associated the image of Girish taking the stage by storm. It was none but Girish introduced Lewis’s theatres to his junior colleagues to acquaint them with modern theatrical art. The overtone Girish maintained in his play, it seems, was done purposefully to impress upon his audience who were still fond of Yatra style. [Dasgupta. 1928] Since he was a boy of 15, Amritalal grew up in the company of an imposing master like Girish. He adored Girish as the ‘Maestro of the Bengali Stage’, yet he did not accept his mode and style personally. The reason he called Girish his ‘Guru’ was ‘something greater’ than his theatrical accomplishment which he learnt from his schoolmate and mentor Ardhendushekhar [Bhattacharya]. To Amritalal, Ardhendu was a creative genius of an actor and a theatre teacher made ‘by God’s own hand’. For Ardhendu, any role was equally good to play. He excelled in major roles like Karta, Ramesh, Abu Hussain, Rodda, Biddadiggaj, Wood, and Bidushak, as well as in the minor roles of Natabar, and Chatulal. It was one of his specialties Ardhendu had that he could make a momentous dramatic feat by playing a petty role involving a word or two to deliver. Using this minimalist artistry Ardhendu could instantaneously compose and stage a play. The first pantomime show, he made with Kshetramoni and Binodini playing his mother and wife respectively and himself a Firangi Saheb, was characteristically narrated by Binodini in Amar Kathahow Ardhendu with his show trapped his audience inside the hall for two hours until rain stopped outside. This was an unannounced show of Mustafi Saheb ka Pucca Tamashabefore it was formallystaged in 1873 in the National Theatre. Ardhendu was not the first Pantomime artist in Calcutta. Dave Carson came to Calcutta in 1861 and was still going strong in 1873 when he confronted Ardhendu. Dave Carson provoked Ardhendu to retort his satire, ‘Bengali Baboo’, which Ardhendu did spectacularly with no hard feelings.

Ardhendu’s pantomime proved to be a unique example of radical theatricals breaking away from the three-century-old lineage rooted in ‘Commedia dell ’Arte’ – an Italian entertainment. It reached the London stage in the early 18th century as pantomime based on classical stories set to music. Until 1843, theatre licensing had restricted the use of spoken word in performances. Gradually witty puns, wordplay and audience participation were added to the repertoire of mime from different sources. As pantomime evolved, more and more domestic stories and topical satires replaced classical stories and folk tales. Pantomime became increasingly focused on elaborate set designs and special effects that demanded huge investment. The Drury Lane pantomime was turned into “a symbol of the British nation – a glittering thing of pomp and humour without order or design”. [Victoria & Albert Museum] Ardhendu’s pantomime was, however, very different from the common British and American versions being impromptu and minimalistic in style, and independent of ready-made storylines, dialogues, costumes, and stage crafts in his inimitable presentation as opposed to stereotypes. Depending upon his ingenuous creative intuition, Ardhendu denied all traditional methods and tools to show his art by empowering his audience to interpret the make-shift world he hinted at with images, sounds and motions on stage as real. The Pantos Ardhendu invented was essentially radical by definition. [Victoria & Albert Museum]

SUM-UP

The theatre history of Colonial Bengal centred around the iconic National Theatre provides a layered landscape of the Bengal Renaissance, often the layers were inseparable. In its ground layer, the Bengal Renaissance bared a movement of powerful secular content that created new national consciousness, patriotism, social reforms and new political ideas unknown in India before the nineteenth century, which served the broad context of the Indian Renaissance. The name National Theatre inherits shades of national characteristics of the Bengal Renaissance, among other things, including their participation with the Hindu Mela, nicknaming Ardhendu Shekhar Mustafi a ‘national asset’ to impress upon his nationalist orientation that he shared with his colleagues [Basu. 1952].

Renaissance however brought about a cognitive revolution, as well, in the minds of ‘creative beings’, which is fundamental to the Cultural Renaissance. The writers, poets, dramatists, scientists, social thinkers, educators, religious reformers, etc. are creators of creative and cross-cultural mentality and humanism [Dasgupta. S]. Literature reflects the issues, problems, and experiences, prevalent in a particular society. The newly awakened social sensitivity was mirrored in the dramatic representations. Stalwart dramatists like Ramratan Tarkaratna, Umesh Chandra Mitra, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, and Dinabandhu Mitra, appeared with their all-time masterpieces to reinforce the sociocultural revolution. Professor Susobhan Sarkar mentions Michael Madhusudan’s poetry, Dinabandhu’s dramas, and the novels of Bankimchandra with which the flowering of the Renaissance began, however, he lets unuttered the names of those young theatre entrepreneurs without whom the epoch-making dramas could never have been staged. The boys dared to bring those literary marvels onto the democratic stage of the public theatre for the first time to benefit the Bengali populace. Their deeds were thankless and daring because, socially, theatre artists were lookdown-able and un-sympathised by the traditionalists. It was more so because founding the public theatre entangles a wretched inner struggle against the adherents of traditional Yatra-Abhinaya.

In their discourses on the Renaissance, Henry Bergson and Arnold Toynbee identified Brahmoistsand neo-Hindu thinkers as groups of ’creative minority’. Predominantly, the creative minority of Bengal intellectuals generated new ideas and tried to put them into social practice for the regeneration of society. [Skorokhodova] The teenage band of four whom Amritalal thought of as the originators, the crucial prerequisites, of the National Theatre, were all have-nots, except the last mentioned, Bhuban Neogi, a scion of the wealthy Neogi family of Bagbazar. It was an enigmatic experience that the long-awaited institution of a public theatre was established by a handful of hard-up teenagers, without a Government grant or funding from the affluent elites of India. In his book, Amrita-modira, Amritalal described their long struggle for the National Theatre in a few couplets extracted here from his narrative poem অমৃত মদিরা:

রাজার সাহায্য নাই নাই নিজধন।

মূলধন মনোবল শরীর পাতন ॥

… …

এইরূপে যুবা-কটি সহায়বিহীন ।

মাঁট হয়ে খাটিয়াছি কত নিশিদন ॥

… …

তবে বঙ্গে নাট্যশালা হয়েহে স্থাপন ।

আলিগলি দেখ এবে যার বিজ্ঞাপন ॥

[Basu. 1903]

(= No Sarkari grant, No penny in hand,

With hard work and will, boys withstand

That was how, no help in sight

They toiled in mud, day and night

Thus Bengal had, Theatre Bengali

See its placards, Gulli se Gulli

[A working translation by the present writer])

References

The good name of the first democratic public theatre was reused thrice unwarrantedly after the original National Theatre collapsed in 1873. The theatre pavilion the boys had constructed at no. 6 Beadon Street was knocked down after being sold out to Gurmukh Singh in 1883. Not enough we know about the originators of the first public theatre, no printable portraits are available to acquaint us with many of those Renaissant Children who awoke in human’s eye new eyesight to see things anew (=‘যে জাগায় চোখে নূতন দেখার দেখা’) [Tagore]. In other words, we lost those who for the first time had empowered the people of Bengal to see anew the realities of life in theatre.

Bandyopadhyay, B. (1939). বঙ্গীয় নাট্যশালার ইতিহাসঃ ১৭৯৫-১৮৭৬. Bangiya Sahitya Parishad. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.477805/page/n5/mode/2up

Basu, A. (1952). অমৃতলাল বসুর স্মৃতি কথা. In পুরাতন প্রসঙ্গ / Gupta, Bepin. Vidyabharati. li.2015.299309/page/n5/mode/1up?q=রাধা+

Basu, A. (1933). ভূবনমোহন নিয়োগী. Basumati, Jaistha 1334. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.100095

Basu, A. (1903). অমৃত-মদিরা. Gurudas. https://ia903400.us.archive.org/7/items/dli.ministry.00216/524.182%2520NC%25209047_text.pdf

Basu, A. (1982). স্মৃতি ও আত্মস্মৃতি (A. Mitra (ed.)). Sahityaloka. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Amr̥talāla%5C_Basura%5C_smr̥ti%5C_o%5C_ātmasmr̥/4LsHAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1 %0A

Bhattacharya, S. (1959). অর্ধেন্দুশেখর ও বাংলা থিয়েটার. Shankar Prakashan. https://granthagara.com/boi/324511-ardhendusekhar-o-bangla-theatre/

Binodini Dasi. (1959). আমার কথা: Amar Katha O Onya-onyo Rachona (S. Acharya, Nirmalya and Chattopadyay (ed.)). Subarnarekha. http://boibaree.blogspot.com/2018/09/blog-post_19.html

Chowdhury, A. (1958). বাংলা নাট্যবিবর্ধনে গীরিশচন্দ্রঃ কলিকাতা বিশ্ববিদ্যালয় গিরিশ বক্তৃতামালা ১৯৫৭. Bookland. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.356671/page/n19/mode/2up

Chowdhury, A. (1959). বাংলা সাধারণ রঙ্গালয়ের শতবর্ষ স্মরণে. Shankar Prakashani. https://ia804706.us.archive.org/34/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.301803/2015.301803.Bangalir-Natyacharcha.pdf

Chowdhury, D. (1995). বাংলা থিয়েটারের ইতিহাস. Pustak Bipani. https://granthagara.com/boi/331880-bangla-theatrer-itihas-by-darshan-chowdhury/

Colligan, M. (2013). Circus and Stage: The theatrical adventures of Rose Edouin and GBW Lewis. State Library Victoria.

Dasgupta, H. (1938). The Indian Stage; v.2. M K Das Gupta. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.228124/mode/2up

Dasgupta, H. (1928). Girish-Pratibha. The author. https://ia801409.us.archive.org/17/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.338283/2015.338283.Girish-Prativa_text.pdf

Foundation, N.-C. (2002). বাংলা পেষাদারি থিয়েটারঃ একটি ইতিহাস. Natya-Chinta Foundation. https://ia601505.us.archive.org/24/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.265707/2015.265707.Bangla-Peshadari.pdf

Gangopadhyay, A. (1927). Girishchandra. Nath Brothers. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.302236/page/n1/mode/2up

Gupta, B. (1952). পুরাতন প্রসঙ্গ (2nd ed.). Bidyabharati. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.299309/page/n5/mode/1up?q=রাধা+

Mitra, R. (1855). বিচিত্র সংগ্রহ. Calcutta Baptist Press. https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/csss/Bibidhartha_Samgraha/Bibidhartha_Samgraha_Vol_05.pdf

Mukherjee, S. (1980). Story of Calcutta Theatres: 1753-1980. KP Bagchi. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.100095

Mukhopadhyay, A. (1972). রঙ্গালয়ে তিরিশ বৎসর (S. Majumdar (ed.)). Dey’s.