চাঁদনি বাজার

SHOPKEEPER’S CITY, CALCUTTA

Calcutta in the 18st century was a new city with enormous mercantile resources. The respectable of its inhabitants were merchants. Men were getting involved in wealth-getting and wealth-spending activities – an economic life led by the shopkeepers. [Biswas]. Calcutta earned the moniker SHOPKEEPER’S CITY even before modern bazaars came up in 1783.

Half a century later, it was the improved company policies and the growing public interest in bazaar farming, Calcutta was looked upon as a great city for living comfortably with foods and drinks and all that facilitate city life. Emma Roberts wonders in late 1830s that there is “perhaps no place in which everything essential for an establishment can be obtained so easily as at Calcutta, carriages and horses are to be hired at a not unreasonable rate, palanquins by the day or half day, and servants of all descriptions of a very respectable class also by the day, these people are called ticca, and if recommended by individuals of known good character, may be trusted. A whole house may be furnished from the bazaars in the course of a few hours, with articles either of an expensive or an economical description, according to the means of the purchaser, a well filled purse answering all the purposes of Aladdin’s wonderful lamp. Never was there a place in which there are greater bargains, for if sales happen to be frequent, the most costly articles, carriages, horses, &c., are to be had for a mere song.” [Roberts]

Visibly, the life in Calcutta was then being supported by a range of service providers from giant merchant houses to feriwalas on foot. There were big firms who acted as auctioneers or commission agents, like Messrs King, Johnson and Pierce; Mouat and Faria; Stewart and Brown; Tulloh & Co. Most of them were in business for decades selling and commissioning wide range of articles from black bear and rabbit skin tippets to Persian attar or essence of roses to cider and other kinds of intoxicating drinks to guns to soda water to Madeira wine. The Europeans, it seems, also engaged themselves, apart from trading in manufacturing businesses dealing with carpentry, glass work, gun making, washing and mangling, distillery, jewelry, coach-making, etc. and catered essentially to the European population residing in the city. [Basu]

CALCUTTA BAZAARS

In maps, old and modern, the entire city of Calcutta may be seen dotted with bazaars, private and public. These bazaars are permanent markets or street-markets consisting of open shops grew mostly as veritable zamindaries for their owners – mostly Indians and few Europeans. Normally bazaars cater the daily necessities, like fresh vegetables, fishes, meats, groceries and stationary items, and also store ready consumer goods. Besides selling of products, there are other classes of ‘bazaar people’ who sell small services of varied kinds, like money-changers, bookbinders, stationers, cobblers, cabinet-makers, umbrella makers, petty agents, leeches-men, idol-sellers, retailers of saccharine dainties, and general dealers do regular business in these bazaars and thoroughfares.’ These are the folks who frequented these bazaars as traders and artisans to share space with regular product shoppers to sustain their livelihood. [Ghose] To a large extent, these job-vendors and artisans found their place in bazaar settlement in response to the changing pattern of consumer behavior in colonial societies. The character of the bazaar and its sales likewise shift toward new varieties of products. Emma was pleased to discover:

“European vegetables may now be purchased in the native bazaars. Indian gardeners have found their account in cultivating potatoes, peas, cauliflowers, lettuces, &c. ; and in travelling particularly, it is of great importance to be able to procure such useful and agreeable additions to the table.” [Roberts]

As we come to know from James H. Harrington’s Report of 1778 [cited in Basu] ] and Mark Wood’s Plan of Calcutta of 1792, there had been around 20 desi bazaars within Calcutta, namely

Burra Bazaar, Bow Bazaar and Lal Bazaar, Bytakhana Bazaar, Sutanuti Hat and Bazaars, Charles Bazaar or Shyam Bazaar, Ram Bazaar, Sobhaa Bazaar, Dharmatala Bazaar, Arcooly Bazaar, Machua Bazaar, Kasaitala Bazaar, Colootala Bazaar, Jaun Bazaar, Hat Jannagar, Hat Rajernagar, Colimba (Colinga) Bazaar, Simla Bazaar and Simla Road Bazaar— as far as the official public bazaars were concerned. Among the private bazaars Tiretta’s Bazaar, Sherburne’s Bazaar, Kashi Babu’s Bazaar (near Sherburne’s) and Gopee Ghosh’s Bazaar in Entally were included.

The three bazaars – Burra Bazaar, Bow Bazaar, and Bytakhana Bazaar were the biggest and busiest bazaars of Calcutta that generally dealt in daily necessities like vegetables, fruits, and of course fishes, besides some other necessities. Hat Jaunnagar, Hat Rajnagar(?) and Kashi Babu’s Bazaar had become special markets dealing in rice, betel leaf and nuts, spices, and paddy straw. Burra Bazaar , the central whole sale market of Calcutta, consists of huge warehouses and plenty of retail shops offering largest variety including, “sundry materials like cutlery, glass ware, glass, earthen ware, fans, blankets, fine mats (shitalpati), coarse mats (chattai), common mats, board mats, wickerwork, coarse cloths, silk ribbon, cotton thread, rope, cotton, leather shoes and slippers, bracelets of all kinds, necklace of wood or beads, goods tirade of brass, small iron boxes or shinduk, iron works, medicinal tools, coconut hookahs, balls for hookah, straw, paddy straw, bamboo, bird cages, umbrellas, stone cases, deshlais or match sticks, etc. were also up for sale”. [cited in Basu]

The diversity of goods on sale bears witness to the grandness of the select few bazaars, which were designed to meet the changing pattern of demands of ‘cosmopolitan population of the city’ in particular. It appears, only in Bytakhana Bazaar, Burra Bazaar and in Sherburne’s private bazaar animals like fowls, geese, duck, horses, pigeons were sold. These apart, goats were available in Burra Bazaar, and ‘homed’ cattle in Bytakhana Bazaar only. All the bazaars of Calcutta had separate places allotted for the sale of fish. Burra Bazaar, Bytakhana Bazaar, Machua Bazaar and Sherburne’s Bazaar had cowrie exchange facilities against gonads. The private bazaars in general seem to specialize in certain articles some of which catered more to the European demands. For example, in those days fireworks were sold primarily in Tiretta’s Bazaar. Among the private bazaars Sherburne’s Bazaar dealt with the greatest number of articles.

EUROPEAN BAZAARS

The owners of three new European bazaars, Edward Tiretta, Joseph Sherburne, and Charles Short came forward to propose setting of modern bazaars in tune with the changing outlook of the Company administration against the backdrop of a ‘civilizing mission’ for improvement of city life. Their proposals also contained distinctive perceptions about a bazaar and references to ‘improve’ upon the existing ill-organized and unhygienic set-ups. To bring about in Calcutta bazaar relatively modern notions in terms of western sensibilities, Edward Tiretta, Joseph Sherburne and Charles Short petitioned individually in May 1782, October 1782 and July 1783, respectively, to the Governor General and Council for permission to build such market places in accordance with the Bye Law of 1781. They pledged to set up bazaars with pucca buildings, tiled shops and stalls instead of the straw huts of the desi bazaars. Mechua Bazaar, although owned and managed since 1775 by a European marketer, Francis D’Mello, was in no way better than the bazaars run by desi masters. In fact, it was since 1882 the shapes of the Calcutta bazaars get changed outwardly and internally for the first time. The new two bazaars, Tiretta Bazaar, and Sherburne’s Bazaar, were set on larger plots, occupying 8-18-4, and 10-1-4 bighas respectively, than Bazaar Sootaluty (3-17-2), and Dhurrumtollah Bazaar (6-10-0). [ Proceedings of the Board of Revenue, Sayer, November, 1794. Cited in Biswas]

SHERBERN’S BAZAAR

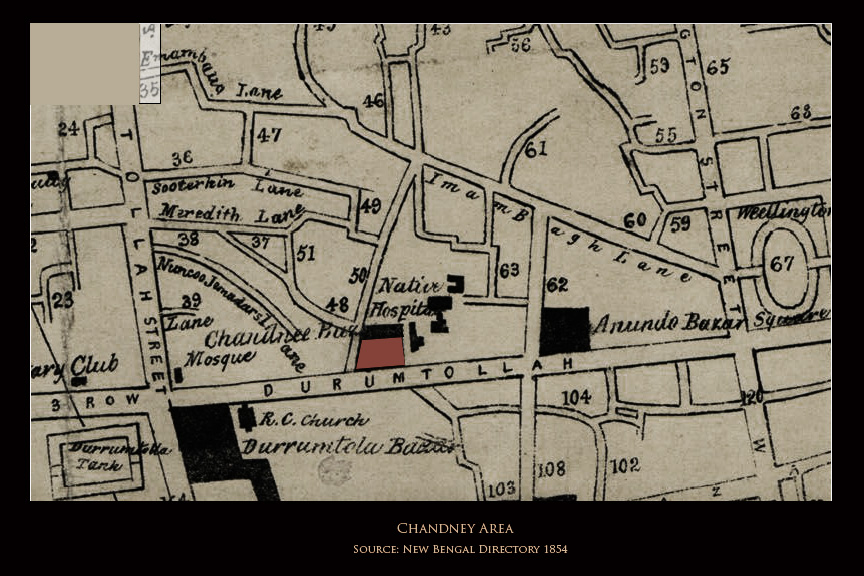

Sherburne’s bazaar, like Tiretta’s and Short’s, followed western model in which hygiene was the primary consideration in its planning to safeguard against deteriorating state of the physical ‘health’ of the city. Huge waste of the native bazaars was regarded largely responsible for infecting the air leading to the degeneration of the atmosphere into poisonous miasmas. These considerations went a long way in the planning of the three newly set bazaars. Sherburne’s bazaar was permitted on a fixed annual rent of Rs.300, revised later to Rs500, and entered the 1785 list of authorized private bazaars of the city. He was given in 1785 an official position of Scavanger [(Hobson-Jobson) ] of the Town of Calcutta, and at rooms, nos. 1 and 3, in his bazaar Sherburne used to discharge his duties of inspection of the goods on sale in Calcutta markets, as well as collection of the taxes. [Calcutta Gazette] The Bazaar was situated in a piece of land, locally known as Ismail Sarang’s Garden, where Chandney Market stands now on the fringe of Dhurrumtollah Street. As we understand, Joseph Sherburne petitioned the Governor General in October 1782, for permission to establish a public bazaar on this very plot he purchased, seemingly from Gokulchandra Mitra. Mitra, who had made a fortune in salt trade and, as it was said, won the Chandney Chawk area in the first Lottery. Behind Sherburne’s Bazaar, Julius Soubise opened his Repository of horses on a large piece of land leading from the Cossitollah down Emambarry Lane. It looks like, the old Chandney Chawk has been more a part of Cossitollah than Dhurrumtollah contrary to popular belief.

After two decades of close association with the Bazaar, Joseph Sherburne passed away at Monghyr on July 18, 1805. His only son, Pultney J. P. Sherburne, died on 28 June 1831. [ Asiatic Journal ] The map of the City and Environment of Calcutta published next year by Jean-Baptiste Tassin, printed the name of Chandney Bazaar for the first time replacing Sherburne’s Bazaar in the site of Chandney Chawk. [Tassin] Although a ‘Chandnee Choke’ and a ‘Chandnee Choke Lane’ found printed in Wood’s map of 1792, there had been no Chandney Market in Calcutta until the Sherburne’s Market wiped out from Calcutta maps. In all probability Sherburne’s Bazaar shuttered down in 1831.

CHANDNEY BAZAAR

When Chandney Bazaar came into existence by 1832, there was no R C Church, no Tipu Mosque, but only the Dhurrumtollah Bazaar opposite Dhurrumtollah Tank stood on roadside since 1796 with Stibbert’s House behind. The oldest institution remained there was the Native Hospital built in 1793 near Chandney. In Talpooker, Pritaram erected his Jaunbazaar House in 1808. “In 1793-94, all over the town there were no fewer than 1114 pucca houses; in 1821 it increased to 14,230” [Biswas] The new suburbs as southern extension of Town Calcutta grew faster with masonry houses built by Europeans and deshi well-to-dos as nucleus of new urban experience of ‘airy habitation’ .

Chandney Market stands on no. 167, Dhurrumtollah Street, at the crossing of Chandney Chawk Street, or Chandney Chawk Bazaar ka Rastah, on the north side of Dhurrumtollah, where Sherburne’s earlier stood. Chandney Bazaar did not replace Sherburne’s Market but came up with a unique identity of its own, completely dissimilar kind of a bazaar, to sell commodities of special kind to altogether different sections of consumers than what Sherburne’s or other bazaars usually target, that is, the common people whose requirements are chiefly food and other daily necessities such as household items, weareables, fashion items – all for ready consumption. In contrast, Chandney Bazaar has never been a place to retail fresh food unlike others. It was not a market for ready-made garments but held shops of cloth lengths and cut-pieces, and tailoring shops for making dresses cheaply and quickly. Chandney was known as a native shopping complex for retailing popular as well newest materials, accessories and tools needed primarily for consumption of journeymen, including artisan, craftsmen, petty tradesmen, mostly pieceworkers like tailors, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, smiths and small manufacturers.

Cotton described the Bazaar as ‘a labyrinth of ill-kept passages, lined with shops, in which may be found a wonderful collection of sundries, from a door nail to a silk dress. The list can be lengthening endlessly by adding items like ‘brass and iron hand-ware, clothes, umbrellas; shoes, stationery, and various other articles of domestic use.’ Cotton, however, unwittingly left a piece of empty advice for shopaholics that “very similar shops and stalls may now be found, but under conditions infinitely more advantageous and comfortable, in the Municipal Market in Lindsay Street, off Chowringhee”. [Cotton] In reality, the two markets have been entirely dissimilar. So much so, no comparison can be possible between the two without distorting facts that still alive. Yet his advice as to the ‘getting favourite picks at pocket-friendly price’ at Chandney by ‘bargaining at your heart’s content’, and that ‘one must essentially be guarded with sharp shopping skill’ may prove helpful for a shopaholic even today.

Chandney Bazaar has never been a market for gentlefolk – sahibs or babus; rarely shoppers go there with families. Most shops were kind of mini warehouse, with no display-windows, no fashion shows. On the whole, the market looked drab, shabby, and uninviting – a mockery of the model market of Sherburne. Chandney, however, was not a ‘second-hand’ market, nor a chore bazaar – a ‘receptacle for all stolen goods’ as Cotton perceived. Chandney Bazaar was essentially, and still it is, a hardware market and not a market of second-hand goods, like some other auction houses and antique bazaars of Calcutta where stolen fancy goods of every description were being sold in the open.

CHANDNEY AMBIENCE

The ambience of Chandney Bazaar has always been disgustingly chaotic – a contradiction of the model picture of the bazaars the city administrators drew in 1783 that Tiretta, Shorts, and Sherburne followed. Outside the Bazaar, the doldrums of Chandney crowd and its unruly traffic overflowed into Dhurrumtollah crossing creating a logjam on the highway.

Chandney Bazaar Interior 2017. Photographs by Olympia Banerjee:

“Gharis wait outside shops, the horses hunched up in their shafts and harness, limp-legged, asleep. The drivers are asleep on the box and syces (সহিস) slumber behind. Water and rubbish on the pavements. The air is heavy with a fetid smell of hookah and food; paint, oil and cycles. In the shadow of the gold-tipped minarets women swathed in sheets clatter their slipperiered feet along the road. … The patrons of the ‘Chandni’ bazaar, scowling, busy; bargaining, wrangling; smiling, smirking; cycle shops, camera shops, pigeon stalls for cigarettes and sherbet. Pavement vendors with their wares in their baskets, pavement barbers assisting the needy with their toilet; street hawkers who pause on the roadway at the; hailing of a customer quarrelsome ghari men lashing their whips at one another.” [Minney ]

Yes, this picture penned by R.J. Minney represents a true to life profile of Chandney – a pet object for a satirist it seems. The pathetic scenario of Chandney inspired even Sukumar Ray to chose the spot to make the road accident happen to one of his comic characters, namely, the over-smart uncle of Ramesh, as we may read in his immortal book, আবোলতাবোল (Aboltabol):

রমেশের মেজমামা সেও ছিল সেয়না,

যত বলি ভালো কথা কানে কিছু নেয় না ;

শেষকালে একদিন চান্নির বাজারে

পড়ে গেল গাড়ি চাপা রাস্তার মাঝারে ।

[সুকুমার রায় ।“সাবধান”,আবোলতাবোল । ১৯২৩]

CHANDNEY BAZAAR, AN AGENT OF CHANGE

Behind the bland homely face of Chandney Bazaar, we may still discover signs of its lost charms that helped Calcutta society to keep pace with the industrial productivity 1832 onward. During the industrial era, the ‘new products’, that is, the newly designed products manufactured by the industrial giants as well as petty workshops, were being increasingly likened by all. There have been also some ‘new products’ designed and developed by the European settlers to help them living comfortably and in style in oriental environment. Society accepts some and rejects others for more than one reason. Market availability, replacement and maintenance are evidently among the main factors for decision-making. Chandney Bazaar stood by the consumers with steady stocks of current and the latest utility products for them to buy replace or repair. Though there were few relatively decent shops, like Nandy’s that used to sell fancy household items, or Kar & Kar the tailoring and garment seller, Chandney has been largely a receptacle of machine-tools, machine parts, and raw materials for the consumptions of small manufacturers, tradesmen, and mechanics. This group of working hands plausibly provided Chandney Bazaar with a unique opportunity to motivate utilization of new products to homemakers more effectively, and to reach families at their homes who hardly ever visit the stinky marketplace – not meant for gentlefolk. That might have been a good reason to postulate that Rev Evan Cotton never had occasion to step inside Chandney Bazaar in person to verify his ideas before attempting to compare it unfairly with Hogg’s Market.

It is unfortunate; Chandney Bazaar does not have enough archival records available for us to distinguish between gossips and facts, so that the worth of its contributions to Calcutta society, in accommodating new products, ideas, new habits, could have been determined with some degree of certainty. Had Chandney Bazaar existed when Captain Thomas Williamson lived in Calcutta (1778-1798), he would have depicted Chandney analytically and objectively in the manner he elaborated on China Bazaar in his prudent Vade Mecum published in 1810. [Williamson] In absence of dependable sources we are being overwhelmed with skewed information disseminated through prints and e-media. Google may take you at once to a number of blogs publicizing Chandney Bazaar of Calcutta in chorus as an exclusive market of electronic goods; while in reality not a single stall of electronics to be found inside, but outside Chandney Bazaar hundreds wait to greet you on the street. I fear the ever increasing nonsense in today’s manufactured information will pose greater challenge to future researchers to investigate issues with scanty documentary evidence, depending largely on literary references and oral traditions, as is the case of Chandney Bazaar of Calcutta.

REFERENCE

Asiatic journal and monthly register for British India and its dependencies. (Jan. 1830-Apr. 1845). London : Printed for Black, Parbury, & Allen. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.095922792&view=1up&seq=4

Basu, Shrimoyee. 2015. “Bazaars In The Changing Urban Space of Early Colonial Calcutta.” University of Calcutta. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/163761.

Cotton, Evan. 1907. Calcutta, Old and New: A Historical and Descriptive Handbook to the City. Calcutta: Newman. https://archive.org/details/calcuttaoldandn00cottgoog.

Ghose, Benoy. 1960. “The Colonial Beginnings of Calcutta Urbanisation without Industrialisation.” The Economic Weekly, no. August 13: 1255–60. http://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/1960_12/33/the_colonial_beginnings_of_calcuttaurbanisation_without_industrialisation.pdf?0=ip_login_no_cache%3Dfc8386086015fc6e2268f71b76bece16.

Minney, Rubeigh James. 1922. Round about Calcutta. Calcutta: OUP. https://archive.org/details/roundaboutcalcut00minnrich.

Ray, Sukumar. n.d. “Sukumar Sahitya Somogro; vo.1.” Calcutta: Ananda. https://archive.org/details/SukumarSahityaSomogro3/page/n17.

Roberts, Emma. 1845. East India Voyager, or the Outward Bound. London: J. Madden. https://books.google.co.in/books/about/The_East_India_Voyager.html?id=rOFAAQAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y.

Setton-Karr, W. S. 1864. Selections from Calcutta Gazettes. Calcutta: Military Orphan Press. https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.195937/2015.195937.Selections-From-Calcutta-Gazettes-1864#page/n5/mode/2up.

Tassin, Jean-Baptiste. (1832). Map of the City and Environs of Calcutta; Constructed chiefly from Major Schalch’s Map and from Captain Prinsep’s Surveys of the Suburbs. Retrieved from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530996458

Williamson, Thomas. 1810. East India Vade Mecum; or, Complete Guide to Gentlemen Intended for the Civil, Military,or Naval Service of the Hon. East India Company; Vol. 2 (2). London: Black, Parry. https://www.scribd.com/document/305022589/The-East-India-Vade-Mecum-Volume-2-of-2-by-Thomas-Williamson.

Wood, Mark. (1792). Plan of Calcutta. Calcutta: William Baillie. Retrieved from https://www.bdeboi.com/2016/02/blog-post_27.html

Yule, Henry ; and Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and f Kindred Terms. London: Murray. https://archive.org/details/hobsonjobsonagl02croogoog/page/n8.

Discover more from PURONOKOLKATA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I came across your very history when researching Joseph Sherburne – many thanks

LikeLike

I thank you, Anne. Glad you find my paper on Chandni Bazar

LikeLike

Dear Ajantrik — went through your blog on Chandni Bazar and Chowk. What is interesting about these blogs that they not only kindle our fading interests on many things that made Calcutta — the great city of our childhood and formative years of adolescence and dreamful days of youth — they also reveal many unknown interesting backgrounds of its otherwise very well known sites. Present one is one such — with astonishingly interesting incidents. We leaved very near to Chandni Bazar and frequented it quite often — yet knew so little of its origin and importance. It was really a Chandni Chowk Bazar — with a Mughal era touch — faintly imitating its famous sister of old classical Delhi. Regards and waiting avidly for a next one–nirmalya kumar majumder

LikeLike

I do always feel the warmth of your love for Purono Kolkata and that encouraged me to carry on my work reassured. It is good to know the topic of Chandney Bazaar interests you so much. There is one other astonishing coincidence for you, that is, we both missed the opportunity to spend hours together whenever we liked chatting about the charms of the old city where both of us spent our early days in the same street without knowing each other. It is something very personal pleasure of finding a missing childhood association, which I like to share with all of my readers. Wish you very best, Dr Majumder!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your kind words sir. Old Calcutta was more than what they say now Oh Kolkata ?! …. its a city of JOY. As a matter of fact it is and always was …. more than these ” adjectives”. I say … if you have not perceived the spirit of ” Purano Kolkata”…. you cannot know the ethos and

pathos of today’s happenings in this great ” South Asian Subcontinent”.Regards …nkm

LikeLike