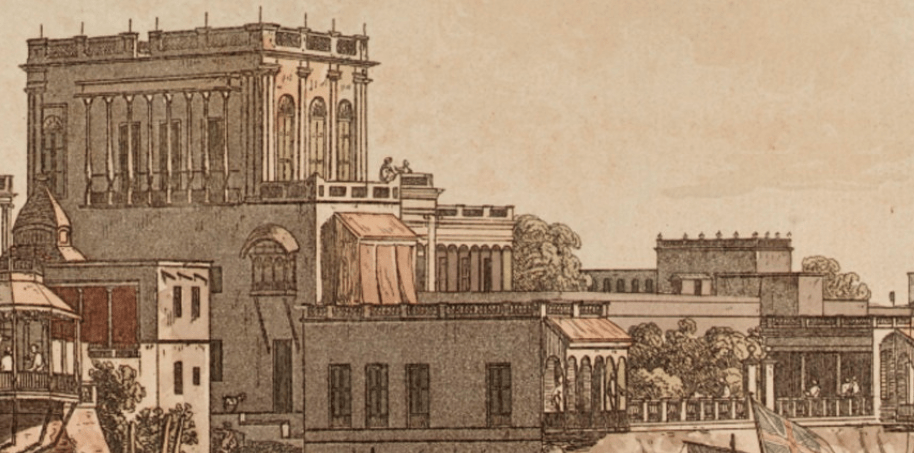

Immortalized in Thomas Daniell’s Gentoo Buildings.

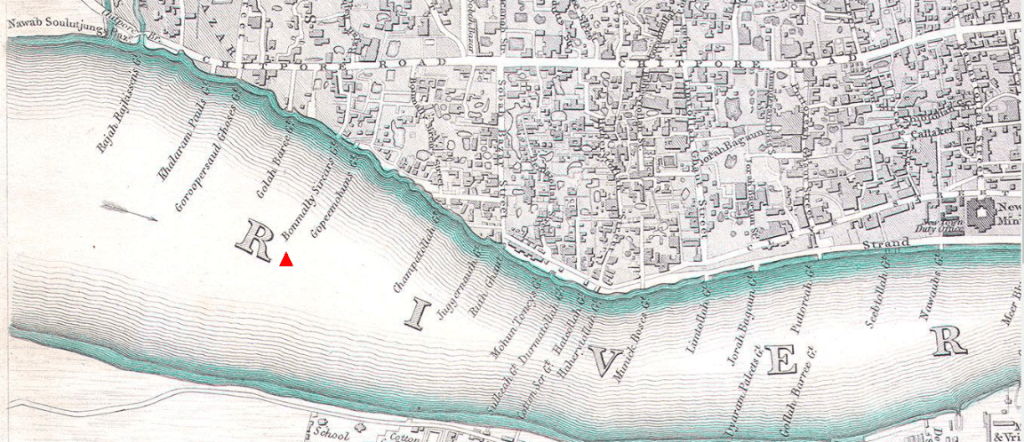

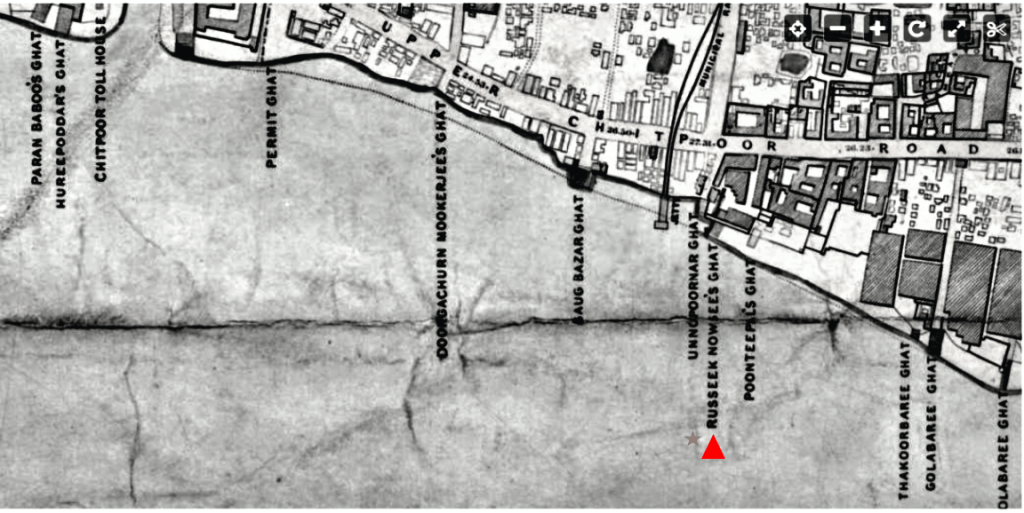

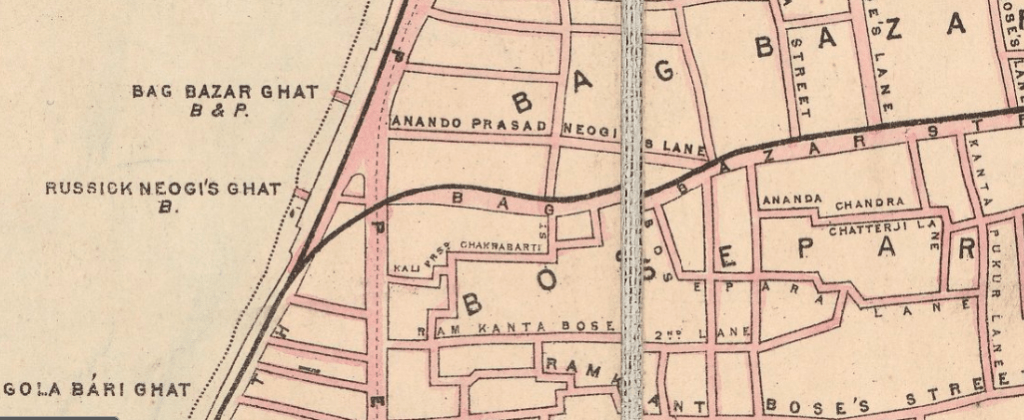

Overview: This paper aims to establish Thomas Daniell’s aquatint ‘Gentoo Buildings’ created around 1787 as the pleasure house of Russick Krishna Neogy on the river Ghat named after him where the home of the National Theatre was lodged in 1872-73. The architectural descriptions available in the texts of contemporary National Theatre personalities accurately correspond with the realistic visual representation made by Thomas Daniell using a camera obscura.Russick Krishna was alive in the 1850s. The wide distance of time discards any possibility of his being the founder of the pleasure house. A comparison of three major vintage maps of Calcutta, Mark Wood 1793, SDUK 1842, and Calcutta Survey 1847-49, reveals that Russick Krishna Neogy Ghat marked its presence for the first time in 1847-48 map, and Bonomally Sarkar Ghat which was being continued to show up since 1793 in Mark Wood’s map disappeared forever. The cartographic evidence suggests a hand change took place between a successor of Bonomally Sarkar and Russick Krishna Neogy sometime between 1843 and 1846. After two and a half decades the property was inherited by his grandchild Bhuban Mohan Neogy, the guardian angel of the National Theatre.

The Painting:

A splendid panoramic view of the north Calcutta township upon River Hooghly is seen overhead. The river floated swarming with sailing boats of medium to small sizes, alongside Bagbazar Ferry Ghat, Annapurna Ghat and the Russick Krishna Neogy Ghat, as marked in 1847-1849 Survey Map 1843 [Simms], standing on shore conspicuously with its magnificent pavilion. The British painter, Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) captured the view in ink and watercolour on paper, settling in a pinnace budgerow exhibiting Union Jack or sometimes sitting on the spacious slope of the ghat.

Daniell gave this early artwork an obscure title, ‘Gentoo Buildings’, before collating it as Plate no. 8 in his album, Views of Calcutta (1788). The riverscape in the environs of Calcutta gentoos (wealthy non-Muslims – a word of Portuguese origin) was indeed one of the rare exceptions and less discussed. Thomas Daniell made it without the least idea that he thus immortalized in his work the long-forgotten historic Home of the National Theatre – the birthplace of the modern Bengali public theatre at the Russick Neogy Ghat site. Daniell was tempted by the elegance of the gentoo building standing out in the panorama of the scenic Ganges. It seems Thomas Daniell made such visuals of the native subject for his private satisfaction because EIC, tipped by George Hardinge (1743–1816), an English judge, writer and MP, brought Thomas Daniell and his nephew William to India on a Company ship to engrave the Englishmen’s happy colonial life in Calcutta, even though the unhealthful city had killed around 60% of expatriates between the founding of EIC and 1775 [Marshall]. Daniell’s neoclassicised view of Calcutta was intended to paint the British as ‘a civilising force’ whose black town was seldom in the same picture plane as the white town. Europeans in Calcutta appreciated these images as a visual argument for virtue rather than the corruption of the so-called nabob [Rasico]. The Daniells did not belong to the Company Painters and were not bound by the EIC terms of employment. Their success in India, however, was dependent upon their equations with EIC servants and influential businessmen close to the ruling powers. Hastings, a notable patron of the arts, left for England in 1785 leaving a legacy of nabobism to exploit endemic art and culture besides material wealth.

The Painter:

On April 7 of the same year, one of the earliest British artists on a painting expedition, Thomas Daniell (1749–1840) left England for India accompanied by his 16-year-old artist-nephew William (1769-1837). The duo arrived in India via China sometime before July 1786 to spend over seven years, travelling extensively the country little known to Europeans capturing the ‘Indian picturesque’ in their artworks [Andrews] and documenting their Indian experience through countless sketches with camera obscura, charcoal and ink wash illustrations, and numerous notes and other studies[Rasico]. Wishing to outdo their predecessor William Hodges, the Daniells made sketches of the landscape using a camera obscura to increase the supposed accuracy of their imagery [UC]. The optical device, available since around 1568, creates an image by focusing rays of light onto a sheet of paper where artists may see “the whole view as it really is” and trace the whole perspective with a pen [National Gallery of Art]. By adopting this optical device Daniells reassured of the realistic value of their works in determining their historicity.

It was not a good time in India when the Daniell duo landed. We understand from Joseph Farrington’s diary that Calcutta never suffered so much from scarcity of money. All the first families were withdrawn and “scarcely twenty persons left in Hindostan, whose fortunes would each amount to twenty thousand pounds” [Garlick]

Despite the uncertainties over the next two years, the Daniells were lucky to get small-time artistic commissions and some miscellaneous jobs [Archer]. In one instance in 1787, the Company hired the duo to clean, repair, and rehang all of the paintings in the EIC’s council room before the new Governor General, Lord Cornwallis arrived [Wilson].

Painting Projects:

Sooner they planned to develop a set of twelve aquatints for sale to meet their living expenses in Calcutta and the needs for travelling through India’s interior. Within a few months of their arrival, Daniells published an advertisement on 17 July 1786 announcing their forthcoming album Views of Calcutta at 12 majestic gold Mohurs, equivalent to one Pound Sterling, to subscribers and for non-subscribers priced 18 Mohurs. For an example of what one could purchase at one gold Mohur, we may recall that Grasim Lebedev priced his ‘Bengally Theatre’ ticket one gold Mohur for the repeat show of Disguise in 1796 [Calcutta Gazette.10 March 1796. cited in Puronokolkata, April 16 2023]. Daniells’ first topographical prints of the colonial capital of twelve etched and aquatinted Views of Calcutta were completed by the end of 1788.

On 7 November 1788, Daniell wrote to Ozias Humphrey RA (1742-1810), his friend miniaturist portrait painter recently in India, “ … You know I was obliged to stand Painter Engraver Copper-smith Printer and Printers Devil myself”. Daniells, however, had engaged Indian assistants to hand-colour their drawings. This was the earliest known picture album of the city circulated in mezzotint and engraving form in Britain throughout the eighteenth century. [Humphrey]

“The depiction of Calcutta provides the viewer with very little detail of the city, other than the Fort and Saint Anne’s Church, and absolutely no sign of South Asian peoples or ecology. Rather, clouds, ships, smoke from ships, and fog sit in the foreground and middle ground, blocking the viewer from seeing much of the city, which is relegated to the background.” [Godrej]

After a long hectic seven years of stay, Daniells left India in May 1793 for England. Back home in September 1794, he and his nephew, William, made several aquatints from the drawings they had amassed and brought together in a collection of one hundred and forty prints issued in six volumes from 1795 to 1808, collectively called Oriental Scenery.

River Ghats:

Thomas and William Daniells were great admirers of the Gangetic scenario and made a series of aquatints capturing the river views. They knew the importance of the strategic location of Calcutta, India’s only inland port which lies 125 miles from the Bay of Bengal on Hooghly linking the Bay of Bengal with the north Indian plain. The British established their port after the Portuguese and the Dutch used Hooghly for trade and constructed jetties. Private traders and merchants added to the number of piers and jetties on the river generating sizeable incomes, about which EIC might not have been too pleased.

When Calcutta was a Bengalese town, the ghats for bathing and worshipping were abundant along the river. The well-to-do families had raised bathing ghats and constructed overhead chandnis fulfilling family conventions, social obligations, and religious duties. The Rajahs of Shovabazar – had quite a few ghats between Kumartuli and Bagbazar. Russick Neogy Ghat stood last in the line like a paragon of Hindu architecture – a contrast of the modern Babu Ghat, then Sahib Ghat, a joint enterprise of the Rani Rashmoni and the EIC. Amritalal Bose in his reminiscence spoke of Russick Neogy Ghat with a chuckle, “Oh, what a charming Ghat it was” [Basu].

Russick Krishna Neogy Ghat:

There were too many river ghats on Hooghly raised and washed out quietly for historians and cartographers to keep track of. Russick Neogy Ghat had existed before 1788 when Daniell etched his Gentoo Buildings. Upjohn and cartographers after him seemingly overlooked Russick Neogy Ghat until John Walker, Geographer to the Hon’ble East India Co. brought out the Map of Calcutta on Actual Survey 1847-49 citing the Ghat.[Simms] On second thought, the possibility of marking the Ghat on old maps with a different name redirects our immediate attention to the lifespan of Russick Krishna Neogy. The dates of birth and death of Russick Krishna, or his son Rajendralal, were unavailable as yet. As some writers suggest, Russick Krishna died after his son Rajendralal’s death, when his grandson Bhuban Mohan in his teens inherited a large section of his property including the famous ghat. Bhuban was 5 years younger than Amritalal Basu (1853-1929), born in 1858. The fact discourages any idea of his grandfather Russick’s mature presence before 1786 to claim the ownership of the Ghat that Daniel meticulously represented. A more acceptable proposition was that in the mid-nineteenth century, Russick had acquired this beautiful property differently cited in old maps constructed sometime before 1876.

This convinces us that the owner of the ghat, where the National Theatre had its home, was owned by Russick Krishna Neogy and named after him. While it settles our immediate issues, we still need, in the greater research interest, to go beyond and attempt to ascertain the original name of the Ghat and its founder, cited in vintage maps differently.

The first authentic map of Calcutta, drawn by A Upjohn [Upjohn] and revised and enlarged by Colonel Mark Wood [Wood], appeared in 1793 with citations of only four ghats on Hooghly in the Chitpur/ Bagbazar vicinity: Old Gunpowder Mill’s Ghat, Rogo Meter’s Ghat, Casheram Meter’s Ghat, Bonomalee Sirkar’s Ghat. The Topographical Survey Map of Calcutta drawn by Charles Joseph in 1841 added quite a few ghats in that area when it wiped out all of the ghats Mark Wood cited except Bonomalee Sirkar’s Ghat which continued to be seen until the 1842 Calcutta map produced by the Society of Diffusion of Useful Knowledge [Society].

The next important Calcutta map produced by the Actual Survey of 1847-49 displaced Bonomalee Sirkar’s Ghat and introduced Russick Krishna Neogy Ghat.

The Actual Survey map indicates a strong possibility of changing hands of the Ghat between Russick Krishna and the successor of Bonomalee Sirkar in the mid-1840s. The ghat was said to be called Battolla Ghat [Calcutta].

Banamali Sarkar was one of the first four wealthiest native gentlemen who lived in colonial Calcutta society famously known for his magnificent mansion, the largest dwelling-house in the city extended from Chitpur Road up to the river bank [Mitra], said to have been constructed before the siege of Calcutta in 1756. It was not improbable for him to go for another beautiful residential house on the river bank adjacent to the ghat he raised, which Thomas Daniell etched in 1786, and Upjohn mapped. Banamali Sarkar, the eldest son of Atmaram Sarkar, had two brothers, Radha Krishna and Hare Krishna. Banamali and Hare Krishna died childless. Radha Krishna had a son, Krishna Mohan Sarkar, popularly called ‘Baro Babu’ for living extravagance. He died in his prime leaving one married daughter, Anandamayee Dasi [Ghose]. This bit of family history suggests that a large part of Banamali’s property went out of their way before Anandamayee dedicated their estate to the family idols. In all probability, during these troubled times for the family, Banamali Sarkar’s Ghat was sold to Russick Krishna sometime between 1842 and 1847 as corroborated by the cartographical surveys.

Location:

In those days of the National Theatre, the site of Russick Krishna Neogy Ghat stood next to the existing Annapurna Ghat beyond Nawab Bazar huts and shops a little further from Doorgacharan Mookerjee’s Bathing Ghat, Bagbazar Bathing Ghat, and the old Eastern Bengal Railway Co.’s Depot. The Ghat was approachable from Lower Chitpore Road through a cluster of shops between nos.216 and 217, near Bagh Bazar General Post Office. [Bengal]

Theatre Home:

Calcutta riverside attracted passersby on boats with the architectural variances of the bathing ghats and temples besides the delightful villas of the wealthy native families. Neogy Ghat was one of Calcutta’s finest river ghats, providing all ghat services and facilities besides its unique aesthetic appeal. We had no idea however how fascinating the ghat looked until we chanced to relate it to the aquatint Gentoo Buildings of Thomas Daniell. We also find ways to identify it with the 2-storied pleasure house, the Bardwari Baithakkhana, of Babu Russick Krishna Neogy, which his successor, Babu Bhuban Mohan Neogy, graciously let his theatre-crazy friends, the hard-up boys of the newly formed National Theatrical Society, to lavishly accommodate their rehearsals in the hall at the rooftop at no cost. Later, Bhuban Mohan also funded the construction of the Great National Theatre at 6 Beadon Street. Without his generosity, the Bengali democratic public theatre never would have come to exist for sure [Amritalal]. The home of the National Theatre was formally shifted from the Bagbazar Russick Neogy Ghat to Bagbazar Nebu Bagan at 11 Ananda Chatterjee Street in early 1873 [National Paper. 6 February 1873. Unverified].

Amritalal Basu spoke of his first visit to Bhuban Neogy’s Baithakkhana house, in his reminiscences. Ardhendu Mustafi, his schoolmate, took him to the place of their rehearsals. On the way, he updated Amritalal about their recent strife and regretted that the group had to do theatre without Girish Babu depending on the barest minimum theatrical amenities [Gupta]. It was good that Bhuban took care of their immediate needs. He allotted the hall upstairs for rehearsing the plays, arranged for the lighting up of the hall, bought a harmonium, and instructed his servants to keep hukkahs, tobaccos and tikkas for the refreshments of the theatre party and the visitors. When Amritalal narrated his old times, the house of Bhuban Neogy on Russick Neogy Ghat was lost forever but was vivid in his sense. Upstairs they rehearsed for Nildarpan in the large hall, below the steps from the bathing ghat sloping down to the Ganges were constantly being washed by plashes of gentle waves. [Basu]

The flights of stairs outlasted the dismantling of the Ghat by the order of the Port Commissioners who considerately kept them intact. Nowhere now existed the magnificent Baradawari building and its spacious salon where in 1873 the National Theatre, rehearsed Nildarpan, Nabin Taposhwi, Krishnakumari, Puru-Vikram, Bharatmata, etc.

When Nauti Binodini went to the theatre for the first time, she was a dainty lassie of around ten. Little did she remember except the ambience of the riverside house of Babu Russick Neogy, the place of their rehearsals and the things in fragments of so beautiful a place built on the skirt of the Ganges. A running verandah overlooked the large upraised bathing ghat with rows of rooms at both sides for men and women folks awaiting their last breath and the final rites on the holy Ganges. The sweet memories of her distant girlhood days were fresh even after half a century. She heard the river flowing with faint ripples. On the long verandah, she ran up and down playfully and dreamed many a delightful dream … [Binodini]

History Crushed Under Wheel:

Since long that noble structure remains hidden under the depth of Ganges. The rails run, folks walk, and boats float over the rubbles of that beautiful Baithakkhana House of Russick Neogy’s [Binodini]. Such was the fate of many other old ghats now cited in vintage maps.

In 1875, the Port Railway took a toll on the historical monument of the Bengali Public Theatre Movement at the Russick Neogy Ghat. To serve the docks area of Calcutta along the bank of the Hooghly the EIC installed the Calcutta Port Commissioners’ Railway (CPCR), a broad gauge port railway. The port railway was launched in stages from 1875 onwards, starting with the first Port-Railway line from Bagh Bazar to Meerbohur Ghat, a distance of 1.76 miles completed in January 1875. The next line from Cossipore (Gun Foundry Road) to Bagh Bazar (Chitpur), a distance of 1.14 miles was completed in June 1878, and, in effect, ravaged the Hooghly River ghats [FIBIS]- a section of which Thomas Daniell depicted painstakingly in his aquatint Gentoo Buildings that we understand today witnessed the birth of the Bengali democratic public theatre.

Endnotes:

Although Thomas was unaware of the connection of his work to Bengali theatre history, his revealing visual documentation evidenced the challenges the homeless National Theatre faced before its dedicated theatre house on Beadon Street was built. We may not forget that Thomas Daniell also made a pathbreaking contribution to the theatre history of colonial Calcutta by etching the famous Playhouse without which we never knew of the existence of the first English theatre of Calcutta. Historians have learnt nothing more than what Daniell documented visually two and a half centuries ago.

Thomas Daniell’s two unique representations of the earliest Calcutta theatre, an English and a Bengali, are yet to be acknowledged by academics as indispensable visual documents for restructuring the historical past of Calcutta’s colonial theatre.

REFERENCE

Andrews, M. (1989). The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape Aesthetics and Tourism in Britain, 1760-1800. Stanford U.P. https://archive.org/details/searchforpicture0000andr

Archer, M., & Lightbown, R. (1982). Picturesque India: India as Viewed by British Artists 1760-1860. Victoria and Albert Museum. https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/India_Observed/V8efAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Basu, A. (1982). স্মৃতি ও আত্মস্মৃতি (A. Mitra (Ed.)). Sahityaloka. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Amr̥talāla%5C_Basura%5C_smr̥ti%5C_o%5C_ātmasmr̥/4LsHAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1 %0A

Bengal Directory. (1876). Alphabetical list of the streets in Calcutta, Howrah, and the Suburbs. In Bengal Directory, 1876. Thacker, Spink. https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/India_Observed/V8efAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Binodini Dasi. (1959). আমার কথা: Amar Katha O Onya-onyo Rachona (S. Acharya, Nirmalya and Chattopadyay (Ed.)). Subarnarekha. http://boibaree.blogspot.com/2018/09/blog-post_19.html

Calcutta Port Trust. (1907). The Story of ghauts of Hooghly River: an unfolding enigma. (Chanda Arup Kumar (Ed.)). Calcutta Port Trust. [Courtesy Animesh Kundu]

Ferrington, J. (1978). Diary of Joseph Ferrington “3 November 1783”: Vol. 2 (K. Garlick & A. Macintyre (Eds.)). Yale U.P. https://archive.org/stream/cu31924102773987/cu31924102773987_djvu.txt B

FIBIS. (n.d.). Calcutta Port and Docks – Railways. FibiWikis

https://wiki.fibis.org/w/Calcutta_Port_Commissioners%27_Railway [Date Accessed: 27-11-2024]

Ghose, L. N. (1871). Indian Chiefs, Rajas , Zamindars; Part 2. The Native aristocracy and gentry. Vol. Part 2. J.N. Ghose. https://archive.org/details/pli.kerala.rare.11274/page/222/mode/2up?q=sarcir&view=theater

Godrej, P., & Rohatgi, P. (1989). Scenic Splendours: India Through the Printed Image. BL. https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Scenic_Splendours/tNwvAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Gupta, B. (1952). পুরাতন প্রসঙ্গ (2nd ed.). Bidyabharati. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.299309/page/n5/mode/1up?q=রাধা+

Humphrey, O. (1928). Letters from Bengal: 1788 to 1795: Unpublished Papers from the Correspondence of Ozias Humphrey. Bengal Past and Present, 35, 113–114. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.32675/page/n133/mode/2up

Marshall, P. . (1976). East Indian Fortunes: The British In Bengal in the Eighteenth Century. OUP. https://archive.org/details/eastindianfortun0000mars/page/n303/mode/2up

Mitra, R. (1952). কলিকাতা-দর্পণ. Subarnarekha. https://granthagara.com/boi/333353-kolikata-darpan-parba-1/#google_vignette

National Gallery of Art. (n.d.). Camera Obscura. The Gallery. https://www.nga.gov/press/exh/2866/camera-obscura.html#:~:text=Camera%20Obscura&text=Washington%2C%20DC%E2%80%94The%20camera%20obscura,screen%20or%20sheet%20of%20paper

Rasico, Patrick D. (2015). Daniells’ Calcutta: Visions of Life, Death, and Nabobery in Late-Eighteenth-Century British India.Thesis. Submitted to the Faculty of History, Vanderbilt, Tennessee. https://irbe.library.vanderbilt.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9af3c035-6a04-4781-ba87-be2d4163435d/content

Simms, F. W., & Thuillier, H. E. L. (1858). Map of Calcutta from actual survey in the years 1847-1849. In John Walker, Geographer to the Hon’ble. East India Co. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7654c.ct001429/?r=-0.046,0.002,0.908,0.384,0

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. (1844). 1842 Map of the City of Calcutta. Chapman & Hall. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/workspace/handleMediaPlayer;JSESSIONID=70269f54-0d3a-4b5a-9340-89da998ff90f?lunaMediaId=RUMSEY~8~1~21006~530098

UC Santa Barbara Library. (n.d.). [Annotaton of] Thomas and William Daniell, A Picturesque Voyage to India; by the Way of China”. U.C. Retrieved November 21, 2024, from https://www.library.ucsb.edu/exhibitions/travel-picturesque

Upjohn, A. (1912). Map of Calcutta and its environs; From the accurate survey taken in the years 1792 & 1793. In Survey of India Office. Survey Office. http://www.museumsofindia.gov.in/repository/record/vmh_kol-R565-C1737-2914

Wilson, C. R. (1895). The Early Annals of the English in Bengal, being the Bengal public consultations for the first half of the eighteenth century; vol.1. Thacker. https://archive.org/details/earlyannalsofeng01wilsuoft

Wood, Colonel. Marc. (1792). 1784 & 1785 Plan of Calcutta. In Commissioners of Police, Calcutta. William Baillie. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/82/Kolkata_Old_Mapg

Discover more from PURONOKOLKATA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.